Economic Issues in Health Care

BE 608

Start recording

Homework Assignment

Homework assignment available on Canvas

- Relates to topics we're discussing today

- Due next week, 11/8, by start of class (upload to Canvas)

Group Project

Last week, several of you brought up challenges with the payment system when we talked about costs.

- Paying per procedure vs. paying for "quality"

- Paying more for care patients get after things get bad (like surgeries) and less for "preventive" care

The question is: what can we do about it?

Group Project

For the group project, you will research one of the attempts to improve this situation. I've tried to select programs that have been in place long enough that there has been some rigorous research on their success or failure. Sign up for your groups on Canvas (6 to 8 per group). There will be two groups for each program.

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Alternative Quality Contract

- CalPERS Reference Pricing

- Medicare Hospital Readmission Program

- Bundled Payments for Care Improvement

- Medicare Shared Savings Program

State Question

Is your state a high spending or low spending state? What factors do you think explain this level of spending?

Spending as % of GDP in the US and OECD countries (source: OECD health Statistics)

Spending by Payer

•What explains the significant role that government plays in every health care system (including the US)?

•How should we think about efficiency in health care?

To answer both, we need to understand how health care is different from other goods.

Two Related Questions

Outline

•Economic Concepts of Efficiency

•How is Health Care Different?

•Applying Economic Concepts of Efficiency to Health Care

•Should we think a bout healthcare as a "good" to be allocated through the market?

Economic Concepts of Efficiency

•The fact that the US spends more than other countries and does not have better health outcomes to show for it, is often interpreted as evidence that the US system is inefficient.

•What exactly does this mean?

Is the US Healthcare System Uniquely Inefficient?

Two Economic Concepts of Efficiency

Productive Efficiency

- Are we producing goods in the most efficient manner?

- Are we getting the greatest possible health improvement from the amount that we are spending? (Could we spend less and get the same benefit?)

- (e.g.) Are invasive procedures the most efficient way to reduce mortality from coronary disease?

Two Economic Concepts of Efficiency

Allocative Efficiency

- Is the market producing the “right” mix of goods?

- Does the last dollar spent on health provide the same benefit as the last dollar spent on other goods or services?

- How does the cost of reducing disease compare to the value of other consumption foregone?

Economic Concepts of Efficiency

It is hard to measure these two concepts of efficiency directly.

However, economic theory tells us that if certain conditions are met, a free market will produce an efficient outcome. They are:

- Homogeneous product

- Large number of price-taking sellers

- Ease of entry and exit

- Buyers and sellers have good (and symmetric) information

- No externalities in production or consumption

When 1+ condition is violated, we say there is market failure, which means that government intervention may improve efficiency.

Economic Concepts of Efficiency

“I will hold that virtually all the special features of this industry, in fact, stem from the prevalence of uncertainty (p. 946)” - Kenneth Arrow

Economic Concepts of Efficiency

Demand for medical care subject to uncertainty about:

Future health and need for care

Demand for insurance

Appropriate treatment and the likelihood of success

Reliance on physician expertise

Asymmetric Information

Adverse Selection,

Moral Hazard

The insurance company lacks info the consumer has

The consumer lacks information the physician has

Principal-Agent Problem

Adverse Selection

Imagine there are two groups of people: the sick and the healthy.

Sick have a 5% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The healthy have a 1% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

What is expected value of each groups's health expenses?

If both groups are risk-neutral, how much would they be willing to pay for insurance?

Adverse Selection

Imagine there are two groups of people: the sick and the healthy.

Sick have a 5% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The healthy have a 1% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

Say the insurance company starts out with 50% sick and 50% healthy.

What are their expected costs per person?

In order to break even "on average", what is the minimum premium they can charge?

Adverse Selection

Imagine there are two groups of people: the sick and the healthy.

Sick have a 5% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The healthy have a 1% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

If they charge a premium of $3000, how many sick people sign up and how many healthy people sign up?

Given this, what is the insurance company's true expected cost?

Adverse Selection

Taking it one step further... suppose WITHIN the group of sick people, half are "very sick" and half are "slightly sick."

The very sick have an 8% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The slightly sick have a 2% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

Currently the premium is at $5000 (the average among the sick).

Who among the sick is interested in buying health insurance?

Adverse Selection

Now assume within the "very sick" there are two groups: the "extremely super sick" and the merely "very sick".... etc.

As premium rises, the relatively healthy want to leave. This makes the premium rise more and the pool of the existing insured get more expensive. Which in turn causes more relatively healthy people to leave...

Eventually, only the most sick remain in the insurance pool, and premiums are very very high.

Health economists call this a "Death Spiral".

State question for next week: What is your state doing to prevent a death spiral in their insurance market?

Moral Hazard

Imagine you break your arm and the doctor offers you a choice of a super fancy decorated cast or a regular cast. The super fancy decorated cast costs $1000 more, but you'd only be willing to pay $100 more for the fancy decorations.

Vs

What would you choose if you're paying out of pocket? What about if insurance covers it?

Moral Hazard (aside)

What do you choose if you're paying for it? What about if you're forcing your students to pay for it?

Vs

$239.00

$0

Moral Hazard

Moral hazard can create economic inefficiency if insurance results in individuals consuming health care that they place a low value on when they gain insurance.

From an economic perspective, this happens when the marginal cost of providing the care exceeds the individual's willingness to pay.

In an ideal world, insurance companies would know what you truly value and only cover those services--but insurance companies don't have this knowledge--this is why moral hazard is an asymmetric information problem.

Oregon Health Insurance Experiment

But how much people actually respond to insurance coverage?

Oregon Health Insurance Experiment

What happened to the people who were "randomly assigned" eligibility for Medicaid?

- Oregon Medicaid program had about 10,000 spots open for low income adults, but many more than 10,000 people wanted health insurance and were qualified.

- Their solution? Made the spots available through a lottery.

- One of the few truly "randomized" experiments in health economics--some people were randomly assigned to receive health insurance versus a control group.

Oregon Health Insurance Experiment

Finkelstein et al 2012 Quarterly Journal of Economics

Oregon Health Insurance Experiment

Finkelstein et al 2012 Quarterly Journal of Economics

OHIE

Caveats: Can't say for sure it's low value--but it's suggestive;

results may be different in other states (Massachusetts reform), or maybe over longer term

OHIE

Some of the most dramatic effects were about financial outcomes

Moral Hazard

How do insurance companies (or public insurance programs) reduce moral hazard?

- Drug formularies: effective "generics" get lower copays than more expensive "branded"

- Coinsurance or copays to give patients "skin in the game," encourage them to only use care they need

- Preauthorization requirements for some plans, "primary care" gatekeepers

Moral Hazard

Insurance companies are also aware that the design of their benefits affects who signs up for their plan.

Adverse selection interacts with these policies to reduce moral hazard.

Example: Generic HIV drugs have been placed on the highest cost-sharing tiers for some individual ACA marketplace plans (Geruso, Layton, and Prinz 2019). Why?

Applying Efficiency Concepts

•Garber and Skinner use the concept of a production function to illustrate how economic concepts of efficiency can be applied to health care.

•Production function comes from the theory of the firm.

~Shows how inputs can be optimally combined to produce different levels of output.

~The frontier represents the best we can do given current technology.

•Two concepts of efficiency

~Productive efficiency: are we on the frontier?

~Allocative efficiency: what is the “best” point on the frontier?

Applying Efficiency Concepts

Production Frontier represents the greatest possible amount of health produced by a given quantity of inputs.

(No guarantee of being on frontier.)

Welfare is Maximized when MB = MC

•Economic welfare is the difference between total benefits and total cost; This will be maximized when the slopes of the TB and TC curves are equal

Welfare Maximization

•Consider a particular medical treatment or intervention. For simplicity, assume that the cost is the same for all patients treated.

•The benefit of the treatment will vary across patients. Imagine that we can order patients in terms of this benefit. Start by providing the treatment to the patient receiving the greatest benefit.

•An efficient allocation is where the benefit received by the “marginal” patient equals the cost of the treatment.

Key economic concept: Thinking on the margin.

Where is welfare/value maximized?

What is the total social benefit from health care in this situation?

What if we continue consuming until N1 or beyond?

Many non-US countries attempt to control over-treatment by limiting quantity. Under what circumstances would this lead to a "better" outcome? A "worse" outcome?

From an economic point of view, "optimal" consumption means saying no to beneficial care when the cost is too high.

One of the many reasons people don't like economists...

•With insurance, patients pay a fraction of the true cost (plus implicit costs associated with discomfort, side effects, etc).

Where would a patient with partial insurance consume? Full insurance?

Revisiting Moral Hazard

Revisiting Moral Hazard

Revisiting Moral Hazard

Copays can reduce some of the welfare loss from moral hazard

A Typology of Medical Interventions

Interventions or technologies can be distinguished by the shape and location of their marginal benefit and marginal cost curves.

- Type I: Highly Cost-Effective (“Home Run”) Interventions

- Type II: Potentially Cost-Effective with Heterogeneous Benefits

- Type III: Interventions with Modest or Uncertain Effectiveness

Type 1A: Low Cost, Highly Effective for Many Patients

Examples

- Antibiotics introduced in the 20th century

- Aspirin, beta blockers after AMI

- The Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking

- Vaccines

- Probably statins

Since costs are low, widespread diffusion does not lead to high spending. In fact, by preventing more serious illness, they may be cost-saving.

Type 1A: Low Cost, Highly Effective for Many Patients

Huge gains to society

Type 1B: Highly Effective Technologies

Because appropriate patients are clearly defined, the cost of over-treatment is low.

Type 1B: Highly Effective Technologies

Type 1B (aside)

Many economists believe the next set of challenges the health system will face is--what do you do when technologies are both HIGHLY effective and EXTREMELY expensive?

E.g. gene therapy

What happened when such medical care was developed previously?

Type 2: Benefits for some, costs for many

Examples

- C- Sections

- Advanced Imaging

- Some Cardiac Interventions (e.g. PCI)

Type 2: Benefits for some, costs for many

Type 2: Benefits for some, costs for many

Type 2: Benefits for some, costs for many

"After orthopedists began billing for MRI, the number of MRI procedures used within thirty days of a first visit increased by about 38 percent." -Baker, Health Affairs 2010

•When evidence on outcomes is limited and physician beliefs vary, the benefit of treatment may be small or even negative.

Examples

- Arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis

- Proton beam treatment for prostate cancer

- Aggressive treatment for end-stage lung cancer

- HDC/Bone marrow transplant for stage 4 breast cancer

- Aduhelm

Type III Interventions

Type III Interventions

-Limited evidence on efficacy

-Received FDA approval despite Advisory Board recommending against

-If covered, would cost the government $100 billion--double the amount spent on prescription drugs for those age 65+

-BUT--it's the only hope for people with Alzheimer's disease

What should be done?

Type III Interventions

This is just one example--some researchers estimate that as much as 30 percent of medical spending in the US is for low value care (e.g., McGinnis et al 2013).

- But--hard to know that an intervention is low value. It goes back to information asymmetries.

Type III Interventions

Even a 1% reduction in cost could fund high quality universal pre-K!

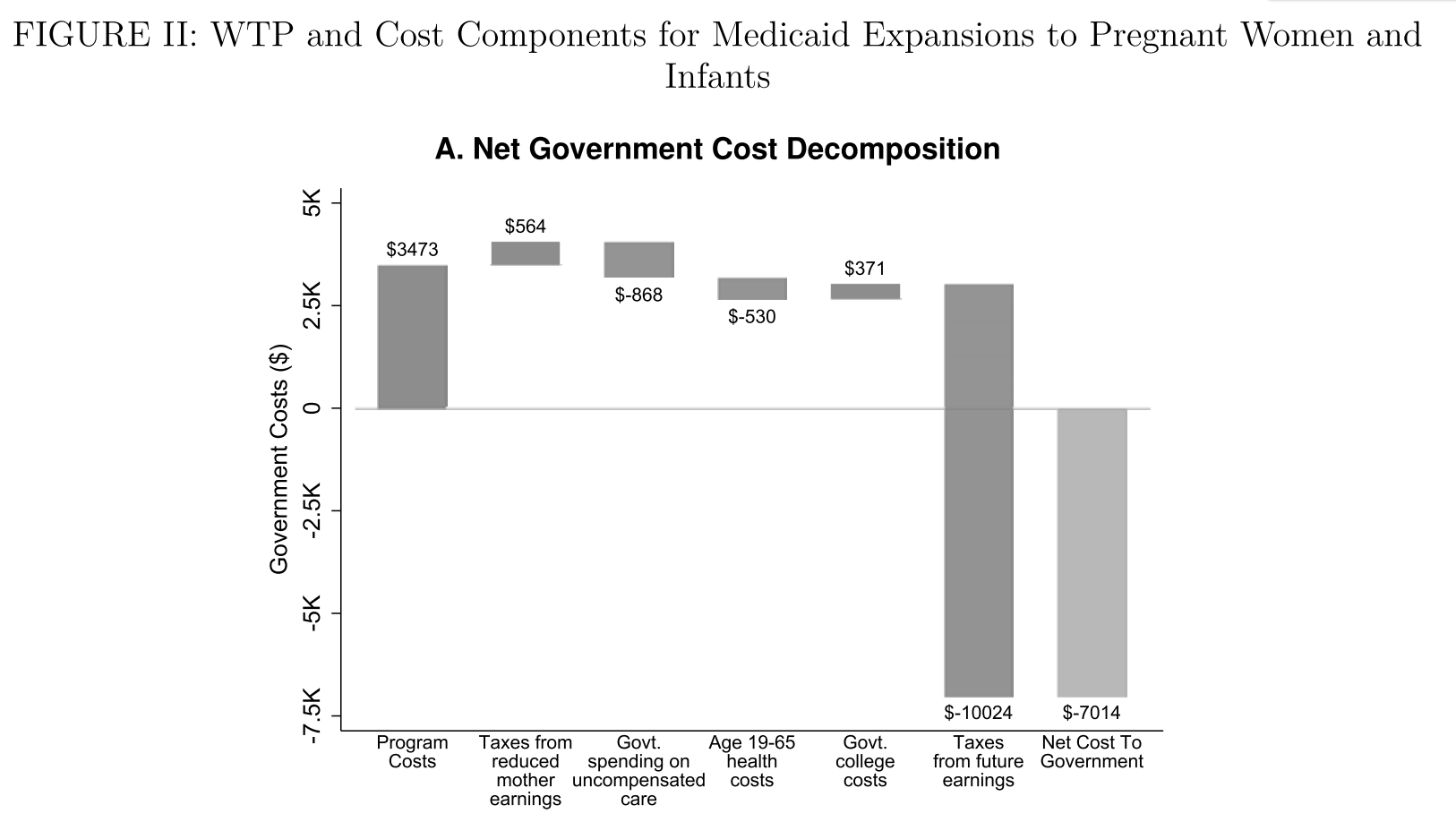

Public policies are often assessed using a method called "marginal value of public funds." This takes the beneficiaries' benefit from the policy ("willingness to pay," measured in dollars) as a ratio of the (net) costs to the government.

Public Policies

Public Policies

Hendren and Sprung-Keyser QJE 2020

Public Policies

Hendren and Sprung-Keyser QJE 2020

https://www.policyinsights.org/

Marginal Value of Public Funds

Typically MVPF is higher for health programs aimed at children

- Longer period over which children can potentially accrue benefits

- Highly sensitive period, small investments can yield big outputs

MVPF calculations are useful for thinking about government budgets, but not all of society wants to "think like an economist."

- If the program increases earnings, thus increasing taxes paid, it will have a very high MVPF.

- But as a society we might want to take care of those who can't earn (e.g. due to disability)--these programs can still be valuable even if the government does not recoup its "investment."

Factors Contributing to Inefficient Health Spending

•The majority of health spending is financed by insurance.

Consumers do not bear the full cost of the care they receive.

•The demand for care is strongly influenced by physicians.

Fee-for-service reimbursement creates an incentive for more spending, even if marginal benefit is low.

•Physicians have imperfect information on the benefits of interventions.

There are large variations in the way existing technology is used.

The Cost Control Challenge

•To achieve value for money, health systems must find a way to encourage the adoption and diffusion of Type I technologies, discourage the use of Type III interventions and target the use of Type II technologies to the right patients.

•Other countries often rely on expert panels to make evidence-based recommendations on the comparative effectiveness and cost implications of medical treatments.

•In the US system it is often private firms (insurers, employers) that are left to make resource allocation decisions.

Is Healthcare A Right or a Good?

How should we think about health care?

Is it a "right" or a "good"?

Should we finance it with social insurance or private insurance?

Some risks are borne individually and some collectively--how should we decide which risks fall into which bucket?

Efficiency and Distributional Consequences of Medicare

When Medicare was established in 1965, only about 25 percent of the elderly had private health insurance.

Low coverage rate can be explained by market failure (adverse selection) and the fact that many elderly could not afford insurance.

Medicare established universal coverage for Americans age 65 and up.

Enrollee premiums, which do not vary by health status, cover only a fraction of total spending. Thus, Medicare represents redistribution

- From young to old

- From healthy to sick

- From higher to lower incomes

Financing of Care for the Non-Elderly

•The Affordable Care Act was designed to address some remaining market failures in health insurance.

•But, fundamentally, the ACA is about redistribution.

•To what extent should public policy enforce transfers

~From young to old?

~From healthy to sick?

~From higher to lower incomes?

For Next Class:

What is your state doing (if anything) to prevent a health insurance

market death spiral? What is your state doing to alleviate moral hazard or adverse selection (e.g. in their Medicaid program)?

We will discuss consolidation trends among providers and insurers.

Please read the two assigned readings.

Copy of Lecture 2

By umich

Copy of Lecture 2

- 116