How to measure unmeasurable?

Introduction to the quantitative methodology

Vít Gabrhel

vit.gabrhel@mail.muni.cz

vit.gabrhel@cdv.cz

FF MU,

30. 6. 2016

Outline

1. Philosophical Standpoint

2. The Role of Theory

3. Methodology

4. Psychometrics

5. Data Analysis

6. Beyond Scientific Method

7. Exercise

Measuring the unmeasurable in the everyday context

Philosophical Standpoint I.

(Post-)positivism (Macionis & Gerber, 2010)

- Information derived from sensory experience, interpreted through reason and logic, forms the exclusive source of all authoritative knowledge

- Theories, background, knowledge and values of the researcher can influence what is observed

- Pursue of objectivity by recognising the possible effects of biases

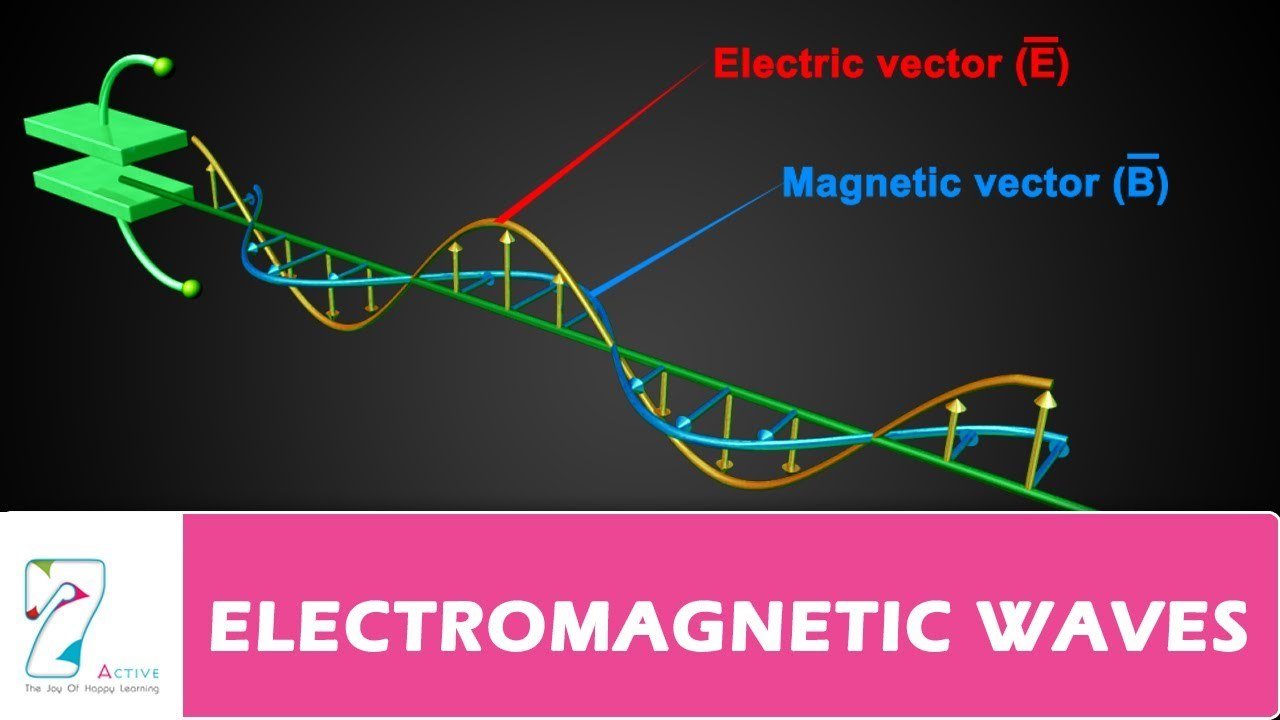

Scientific realism (Shapere, 1982)

- Epistemically positive attitude towards the outputs of scientific investigation, regarding both observable and unobservable aspects of the world.

-

The distinction here between the observable and the unobservable reflects human sensory capabilities:

- The observable is that which can, under favourable conditions, be perceived using the unaided senses (for example, planets and platypuses);

- The unobservable is that which cannot be detected this way (for example, proteins and protons)

Philosophical Standpoint II.

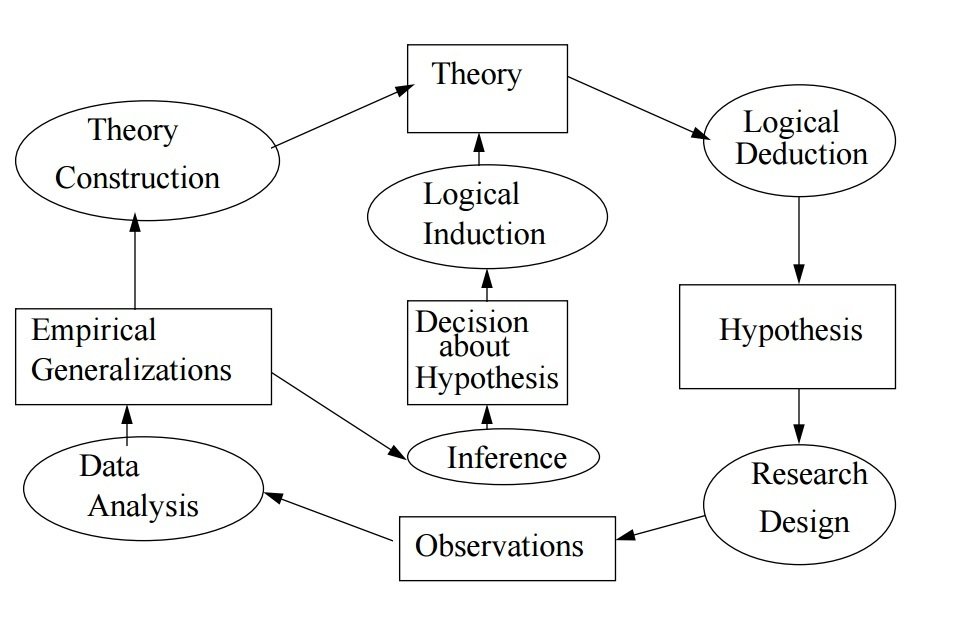

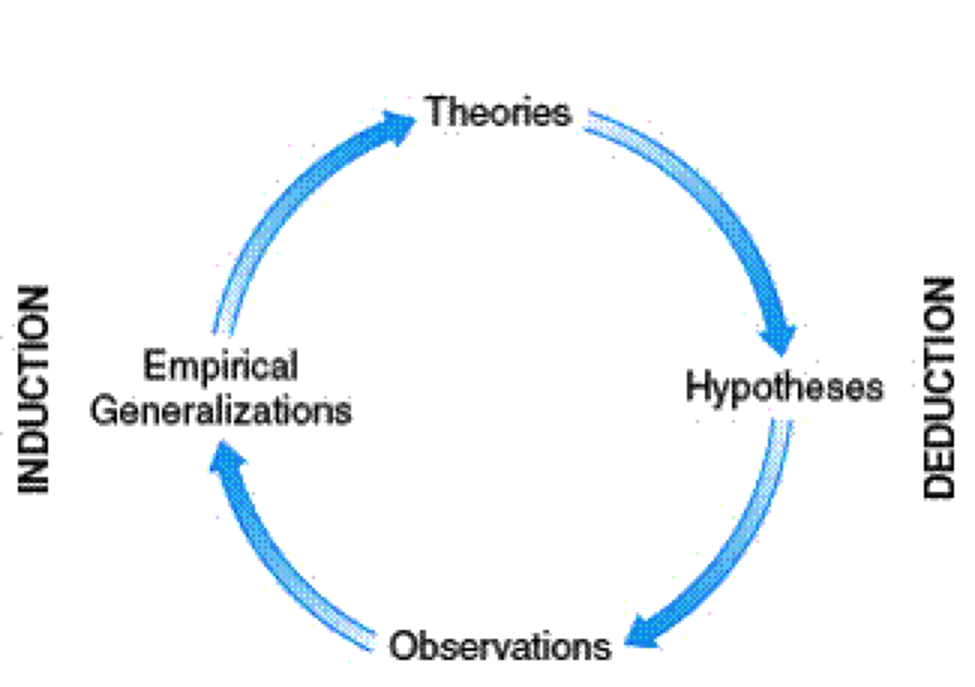

Scientific Method

Theory, deduction, hypothesis, data collection, induction, acquiring new knowledge or correcting the previous knowledge

Wallace wheel of science (Wallace, 1971)

Philosophical Standpoint III.

Empiric Approach (Babbie, 2010)

Scientific knowledge about the world is based on systematic observation

Personal experience, although undoubtedly legitimate, may represent a selective part of the reality

- However, each of us can have a different experience

Unsystematic observations may lead to various errors and biases

Inaccurate observations - Most of our daily observations are casual and semiconscious. That's why we often disagree about what really happened.

Overgeneralization - "He is one of them. They are all the same."

Selective observations - Confirmatory bias

Illogical Reasoning - "The exception proves the rule."

Heuristics - Representativity, Anchoring and Adjustment, Availability etc.

Philosophical Standpoint IV.

Falsification (Popper, 1968)

-

Falsifiability or refutability of a statement, hypothesis, or theory is the inherent possibility that it can be proven false, either by logical argument or evidence.

- In other words, it must be possible to check every claim

about the reality

- In other words, it must be possible to check every claim

- Thus, the term falsifiability is sometimes synonymous

to testability

"How many angels dance on the head of the pin?

Philosophical Standpoint V.

Stochastic or Probabilistic Principle (Babbie, 2010)

Every claim has a degree of certainty - an exception does not mean that a pattern does not exist.

This applies for both social and natural sciences (e.g. subatomic physics or genetics are based

on probabilities)

Educational mobility

"There is a tendency to reproduce achieved educational level through the generations."

(e.g. Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977)

Gender differences in salary

"A particular woman may well earn more money than most men, but that provides small consolation to the majority of women, who earn less. The pattern still exists."

The Role of Theory I.

"There is nothing more practical than a good theory."

Kurt Lewin

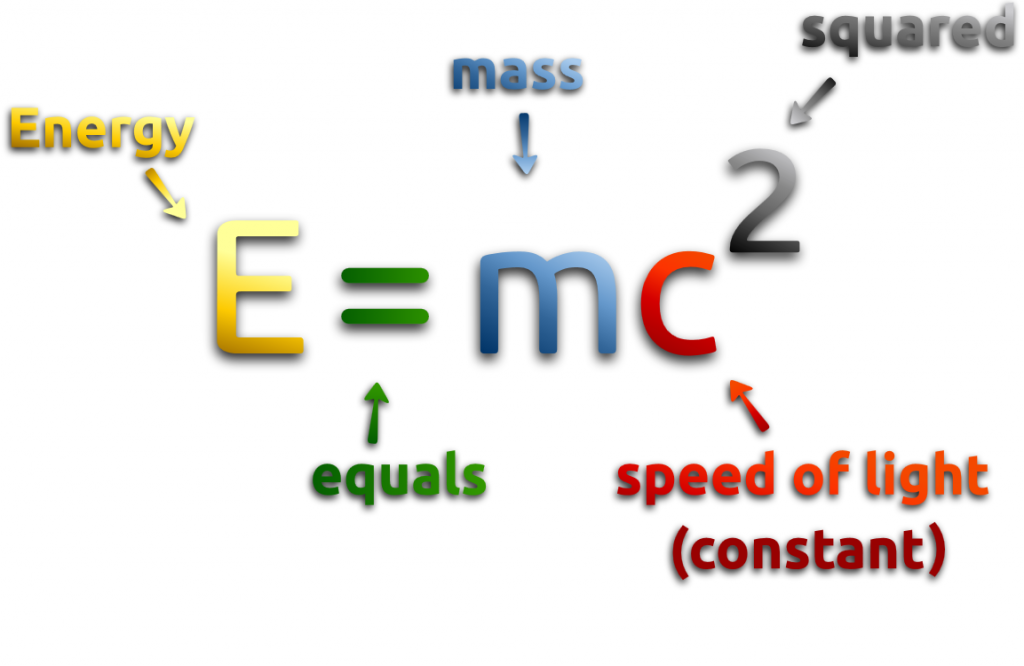

Theory is a systematic explanation for the observations that relate to

particular aspects of life.

- Answers questions such as "What is it?" or "Why does this happen?"

It is a model of reality that allows us to understand the reality,

to predict future outcomes based on previous inputs

Scientific theory versus common sense (Babbie, 2010)

The Role of Theory II.

Tradition

By accepting what everybody knows, we avoid the overwhelming task of starting from scratch in our search for regularities and understanding.

At the same time, tradition may hinder human inquiry. Moreover, it rarely occurs to most of us to seek a different understanding of something we all "know" to be true.

Authority

We benefit throughout our lives from new discoveries and understandings produced by others. Often, acceptance of these new acquisitions depends on the status of the discoverer. We're more likely to believe that the common cold can be transmitted through kissing, when you hear it from an epidemiologist than when you hear it from your uncle Pete.

The advertising industry plays heavily on this misuse of authority by, for example, having movie actors evaluate the performance of automobiles

The Role of Theory

Example

The affect component reflects one's personality, e.g. through one's preference for individual or group work.

Learning styles represent such setting of individuals that allow them to receive, proceed, store and restore contents that they try to learn to the most effective extend (James & Blank, via James & Gardner, 1995).

As such, learning styles comprise of cognitive, sensual and affect components or dimensions.

Student Styles Questionnaire is inspired by the Psychological types of C. G. Jung and Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

Extraverted-Introverted

Seeking company of others versus preference for one's own internal world

Practical-Imaginative

Interested in facts versus imaging possibilities

Thinking-Feeling

Information analysis and critical approach versus deciding upon one's personal standards

Organized-Flexible

Preference of structure and plan versus preference of open state of things

External validity and the studied sample

Methodology I.

Who/What are we trying to observe?

Importance of the external validity of the results

If the sample differs from the population in a key characteristic, we can't generalise the results on the population

Importance of the internal validity of the results

If there is a specific sub-sample is with a key characteristic that differs from the overall sample, the results may be caused not by our measurement, but by this specificity.

Sampling procedures

Probabilistic

Random simple, Stratified, Cluster, Multi- staged, Random walk, etc.

Non-probabilistic

Convenient, Snowball, Quota, Opinion poll, etc.

Methodology II.

Construct validity and the used method

What procedures do we use in order to measure our latent variables?

Research design

Experimental - We are looking for causality

- Limited number of variables, some things can't be assessed experimentally both for technical and ethical reasons

Correlational - We are looking for association

- We don't know the direction of the relationship, i.e. causality

Research tools

Experimental manipulations - instruction, incentive etc.

Questionnaire - items on subjective (attitude scales such as Likert, Thurnstone, Guttman, Semantic Differential, Q-sort, etc.) and objective (socio-demographics) topics

Unobtrusive research - observation, content analysis, analysing existing statistics, physical footprints etc.

Methodology III.

Internal validity and the design of the study

Threats to the internal validity

History, maturation, reactivity, selection bias, etc.

How certain we could be about our results?

Internal validity stands for the degree of our certainty that the results are a product of our research and not of some unobserved phenomena.

It is especially important for experimental research designs.

Methodology

Example

Non-probabilistic sampling - convenient sample

N = 520 (36 % Females)

Age: M = 17,3 (SD = 1,4)

Variety of study programmes: 9 schools, more than 20 classes

Questionnaire as a method of data collection

Psychometrics I.

Reliability

How accurately do we measure what we want to measure?

Is our measurement consistent?

- Do individual items relate to each other?

- Psychometric paradox - the more items have the similar content, the more reliable they are. At the same time, the more items have the same content, the less valid they are as they measure the same limited information

How accurately do we measure over time?

- Can we repeat the measurement?

- Is the variable stable over time?

Does our method have a parallel?

- Are the two tests on the same topic equal?

Psychometrics II.

Validity

What do we measure?

How plausibly did we capture the concept?

Content validity - Is the content of the method aligned with the theory?

Factor validity - Does the obtained factor structure reflect the theoretical assumptions?

To what degree the concept relates to other concepts?

Predictive validity - Does the variable help us to predict some phenomena based on the theory?

Concurrent validity - Is the variable aligned with other variables relevant according to the theory?

Incremental validity - Does one method assessing cognitive abilities explain something more in comparison to the different method assessing cognitive abilities?

Differential validity - To what degree is some variable (e.g. cognitive ability) different from the other, unrelated variable (e.g. personality trait)?

Psychometrics

Example

Reliability

Validity

The Czech context

Extroverted-Introverted – 23 items, 445 participants, KR20 = 0.82

Practical-Imaginative – 16 items, 454 participants, KR20 = 0.50

Thinking-Feeling –10 items, 480 participants, KR20 = 0.58

Organized-Flexible – 26 items, 451 participants, KR20 = 0.62

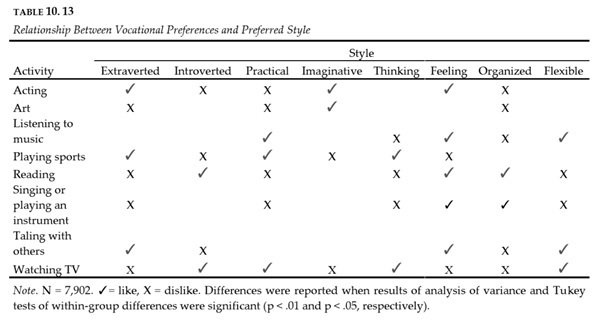

- 54 comparisons. In 42 of them, in contrary to the manual of the method, no differences were found.

- Even with significant results, the interpretation of the remaining 12 comparisons is not straightforward due to a potential intervening variable, i.e. gender.

- Thinking-Feeling and gender: Mm=3,88 (SD=1,93), Mf =6,11 (SD=2,16)

- Aspiration for teacher occupation and gender: Male: 21% were interested, Female: 40% showed interest

Authors of the method argue that reliability in terms of internal consistency is not a suitable indicator of reliability, especially because of dichotomic nature of items and their limited number. According to them, this fact could undermine the internal consistency of SSQ as it is a short questionnaire (Oakland et al., 1996).

Data analysis

Procedures

Were the chosen analytical procedures able to answer the research question/problem? Were they correctly used? Were their limits reflected?

Statistical significance and other indicators

Did authors rely on arbitrary criteria such as statistical significance or did they also used other needed information, e.g. size effects?

Interpretation

Is the interpretation of the results aligned with the data? Is there any exaggeration?

Data analysis

Example

- No size effects, relies only on the "p" value in the "family-wise error rate" scenario

- Unreflected limits of the used method (Cattel 16PF)

- Optimistic interpretation of the problematic results

Beyond Scientific Method

Normative versus descriptive nature of the science

"Scientific theory-and, more broadly, science itself-cannot settle debates about values. Science cannot determine whether capitalism is better or worse than socialism. What it can do is determine how these systems perform in terms of some set of agreed-on criteria. For example, we could determine scientifically whether capitalism or socialism most supports human dignity and freedom only if we first agreed on some measurable definitions of dignity and freedom. Our conclusions would then be limited to the meanings specified in our definitions. They would have no general meaning beyond that." (Babbie, 2010, p. 11)

Ethics

- How does the specific research contribute to individuals, to society?

- What is the price of the "proggress"?

Exercise

- Split into small groups

- Think about some characteristic (latent variable) that may be useful in your work.

- How do you define it? What is its content?

- Do you have any existing theory you can draw upon? How does your concept it relate to other relevant variables?

- How would you observe the characteristic?

- What are the limitations of your approach?

References

- Babbie, Earl. 2010. The Practice of Social Research (12th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth.

- Shapere, D., 1982, ‘The Concept of Observation in Science and Philosophy’, Philosophy of Science, 49: 485–525.

- Bourdieu, P., Passeron, J. C. 1997. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage Publications.

- James, W., Gardner, D. (1995). Learning styles: Implications for distance learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 67, 19-31.

- Oakland, T., Glutting, J. J., & Horton, C. B. (1996). Student Styles Questionnaire: Star qualities in learning,

- relating, and working. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

- Popper, K. R. (1968). The logic of scientific discovery. New York: Harper & Row.

- Macionis, J. J., and Linda M. Gerber, Sociology, Seventh Canadian Edition, Pearson Canada

- Wallace, W. (1971). The Logic of Science in Sociology.

Further resources

Research Methodology

Schutt, Russell K. 2004. Investigating the Social World. The Process and Practice of Research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

BLAIKIE, N. 2000. Designing Social Research. Cambridge: Polity.

Ridenour, C. S., Newman, I. (2008). Mixed Methods Research. Exploring the Interactive Continuum. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press

Statistics

Morgan, S. E., Reichert, T., Harrison, T. R.: From numbers to words. Reporting statistical results for the social sciences. Allyn & Bacon, 2002.

Howell, David C. [DH] Statistical methods for psychology. 8th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2013

Field, A.: Discovering statistics using SPSS/R/SAS/etc.

Psychometrics

Furr, R. M., & Bacharach, V. R. (2014). Psychometrics : An Introduction, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

Philosophy

Borsboom, D. (2005). Measuring the Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chakravartty, A. (2015). Scientific Realism. In Edward N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2015/entries/scientific-realism Monton, B., & Mohler, C. (2014). Constructive Empiricism. In Edward N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/constructive-empiricism Chang, H. (2009). Operationalism. In Edward N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2009/entries/operationalism

How to measure unmeasurable?

By Vít Gabrhel

How to measure unmeasurable?

- 1,588