Computational Biology

(BIOSC 1540)

Feb 13, 2025

Lecture 06B

Read mapping

Methodology

Announcements

Assignments

Quizzes

CBytes

ATP until the next reward: 653

After today, you should have a better understanding of

The purpose of reference-based mapping

Understanding how we get our reads

Cells will transcribe these genes into mRNA (i.e., transcripts)

We collect, convert to complementary DNA, and then amplify

Suppose we have the following three coding (i.e., genes) and non-coding regions with introns and exons

DNA

Understanding how we get our reads

Fragmentation and sequencing

FASTQ reads

Each RNA-seq read represents a small fragment of a transcript

Our purified sample

The Goal of Read Alignment is to Reconstruct Gene Expression Patterns

By mapping reads to a reference genome or transcriptome, we can:

- Identify which genes are active in a sample.

- Measure the relative abundance of different transcripts.

- Detect novel isoforms and alternative splicing events.

DNA

Reads

Read mapping determines where in the genome did these reads originate from.

RNA-seq must account for alternative splicing

DNA

Reads

Unlike DNA sequencing, RNA sequencing includes spliced transcripts.

Key problem: Reads from mRNA span exon-exon junctions, but the genome contains introns.

Solution: Transcriptomic aligners must allow for gapped alignments that bridge exon-exon junctions.

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Hash-based methods for handling introns

Activity

Read mapping exercise

The reads below were built by taking random words, slicing three letters, and then concatenating without spaces (all lowercase)

In groups, please work together to determine which words were used for your read

Be prepared to explain how you approached the problem

Danny loved spotting shapes in the clouds and had an entire journal filled with sketches of dragons, castles, and sailing ships. One day, he noticed a small cloud following him, shifting to match whatever he imagined. He tested it by thinking of a giant ice cream cone; sure enough, it transformed before his eyes. Delighted, he ran home, wondering how much fun he could have with a personal cloud. His only concern was making sure it didn’t rain inside his room.

Let's consider this short story as our genome containing coding and non-coding regions

0. danclodrashi

"Danny clouds dragons ships"

1. entmagcretra

2. spomatwoncon

3. notgiasaibed

4. lovdrathirai

?

?

?

?

We could do maybe one or two in a few minutes

What about doing 30?

We need to map millions of reads to our genome, so how could we approach this computationally?

danclodrashi

lovshaentjou

spofilskecas

saionenotsma

clofolshimat

whaimatestthi

giaicecrecon

surenotratrig

befeyedelran

homwonmucfun

cloonlconmak

surdidraiins

danlovsposke

shajoufildra

cassaishiday

notclofolshi

matwhaimates

thigiaicecre

consurenotra

couhavwitper

rigbefeyedel

ranhomwonmuc

funcouhavwit

percloonlcon

maksurdidrai

insbeddanlov

sposhacloent

joufilskedra

casnotsmaclo

folshimathwa

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Hash-based methods for handling introns

K-mer indexing

We can pre-compute k-mer locations of our story

Danny loved spotting shapes in the clouds and had an entire journal filled with sketches of dragons, castles, and sailing ships [...]

We can chunk our story into k-mers and store where in the story they occur

"dan": [0]

"ann": [1]

"nny": [2]"clo": [35, 153, 382]

"lou": [36, 154, 383]

"oud": [37, 155, 384]

danny

clouds, cloud, cloud

"ing": [17, 116, 165, 178, 233, 335, 412]spotting, sailing, following, shifting, thinking, wondering, making

We can store these k-mers and indices and then use these to find potential sources

Mapping a read to our genome involves checking where k-mers exist

danclodrashi

Danny loved spotting shapes in the clouds and had an entire journal filled with sketches of dragons, castles, and sailing ships [...]

dan, clo, dra, shi

Read

Genome

Query k-mers

Check if k-mers are in our genome and the starting index of that k-mer

"dan": [0]

"clo": [35, 153, 382]

"dra": [92]

"shi": [120, 173]clouds, cloud, cloud

danny

dragon

ships, shifting

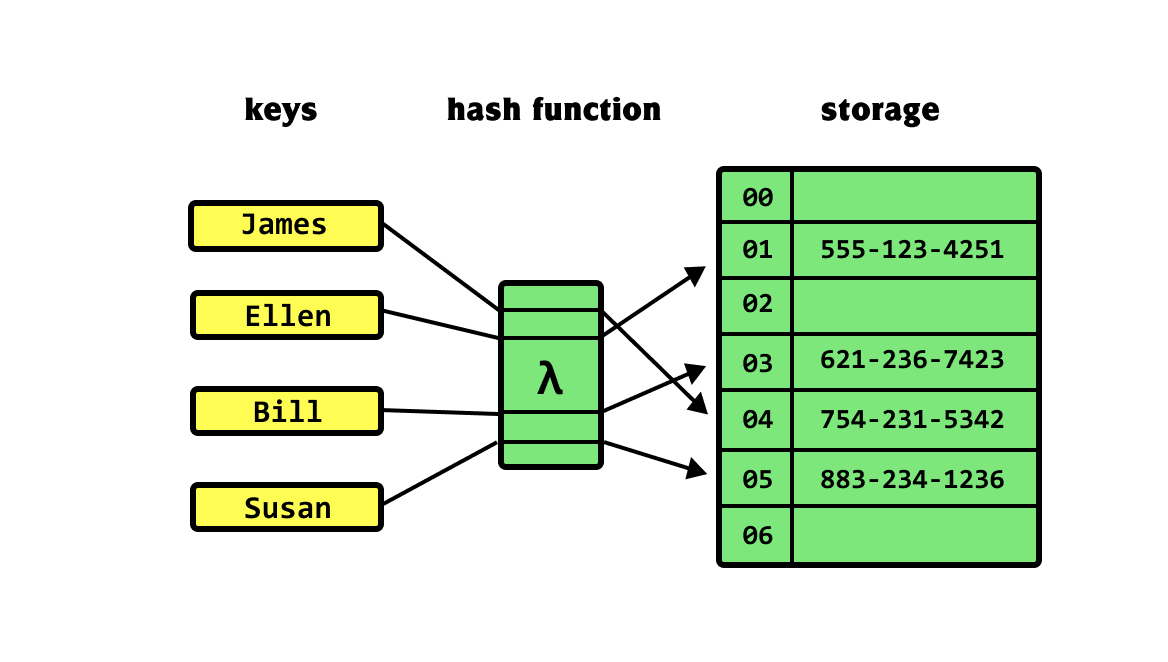

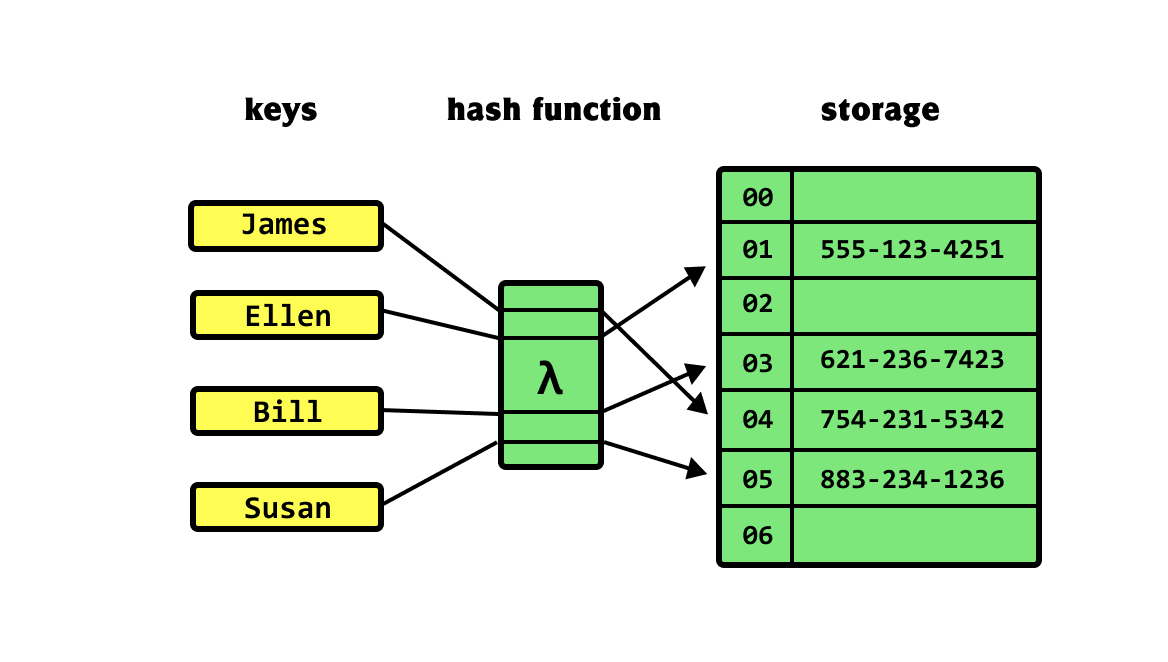

This data structure is called a hash table (i.e., dictionary in Python)

Hash tables link a key to a value

Keys represent a "label" we can use to get information

Example: Phone book / Contacts list

Name

A "hash function" determines where to find their number in our computer's memory

Number

Hashing our reference genome seeds our hash table with k-mer locations

5-mers

TACGT, ACGTA, CGTAC, GTACG, . . .

Reference genome

0

10

TACGTACGATAGTCGACTAGCATGCATGCTACGTGCTAGCACGTATGCATGCATGCATGCC

20

30

40

50

60

We hash our k-mer, and add the starting index where that k-mer occurs in our reference genome

TACGT

[1, 40]

h(k)

ACGTA

[0, 29]

k-mer location in genome

k-mer

Hashing our RNA-seq data provides quick lookups of our reference genome

Query a k-mer read to get indices that of possible reference genome locations

Reference genome

Hash table

TACGT

[0, 29]

ACGTA

[1, 40]

k-mer location in genome

k-mer

h(k)

0

10

TACGTACGATAGTCGACTAGCATGCATGCTACGTGCTAGCACGTATGCATGCATGCA

20

30

40

50

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Suffix arrays for efficient substring searches

Hash-Based Alignment: Divide and Conquer

A "DNA dictionary" with quick lookup and direct access to potential matches

Pros

- Easily parallelizable

- Flexible for allowing mismatches

- Conceptually simple

Cons

- Large memory footprint for index

- Can be slower for very large genomes

"dan": [0]

"clo": [35, 153, 382]

"dra": [92]

"shi": [120, 173]Suffix trees compress all k-mers into a single data structure

NA

NA$

$

4

2

0

1

3

5

A

$

NA

$

NA$

Root node

(Start here)

BANANA

$

A suffix tree is used to find starting index of suffix

Nowhere.

Edge

Node

Leaf node

Split point

Suffix start index

Next part of suffix

Where does start?

AANA

Index 2.

Example: Where does

start?

NANA$

Note: We use $ to represent the end of a string

Suffix arrays are memory-efficient alternatives to trees

BANANA

$

Requires less memory, but is also less powerful

1. Create all suffixes

2. Sort lexicographically

BANANA

$

ANANA

$

NANA

$

NA

$

ANA

$

A

$

$

3. Store starting indices in original string

6

5

3

1

0

4

2

$ comes before letters for sorting

String index

BANANA

$

ANANA

$

NANA

$

NA

$

ANA

$

A

$

$

Suffix

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) string compression

Compression reduces the amount of data we have to store

"Alex keeps talking and talking and talking and talking and eventually stops."

Suppose we need to store this string:

How could we store this string and save space?

"talking and talking and talking and talking and"

"talking and" 4

=

"Alex keeps talking and talking and talking and talking and eventually stops."

"Alex keeps" + "talking and" 4 +"eventually stops."

Run-length encoding

Not all strings have repeats

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec iaculis risus vulputate dui condimentum congue. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas.

Can you find any repeats?

How can we force repeats?

Sorting the letters does!

.aaaaaaaaaaaabbcccccccccddddddeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeefggghiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiillllllllmmmmmmmmnnnnnnnnnnoooooooopppppqqrrrrrrrssssssssssssssssstttttttttttttttttttuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuv

a12b2c9d6e23f1g3h1i16l8m8n10o8p5q2r7s17t19u15v1

Run-length encoding

Sorting lexicographically forces repeats, but loses original data

The Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) is a way to sort our strings without losing the original data

(And also search through it!)

Developed by Michael Burrows and David Wheeler in 1994

Basic concept of BWT

- Append a unique end-of-string (EOS) marker to the input string.

- Generate all rotations of the string.

- Sort these rotations lexicographically.

- Extract the last column of the sorted matrix as the BWT output.

BANANA

$

A

$

BANAN

NA

$

BANA

$

BANANA

ANA

$

BAN

NANA

$

BA

ANANA

$

B

BANANA

$

A

$

BANAN

NA

$

BANA

$

BANANA

ANA

$

BAN

NANA

$

BA

ANANA

$

B

ANNB$AA

BANANA

First column is more compressible, but we lose context and reversibility

(We can also get first column by sorting the output)

After today, you should have a better understanding of

FM-index for efficient substring searches

Enhancing BWT for Rapid Searching

ABRACADABRA$

ABRACADABR

$ABRACADAB

BRA$ABRACA

BRACADABRA

CADABRA$AB

DABRA$ABRA

RA$ABRACAD

RACADABRA$

ADABRA$ABR

ABRA$ABRAC

A$ABRACADA

ACADABRA$A

$

A0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B0

B1

C0

D0

R1

R0

A0

R0

D0

$

R1

C0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B1

B0

ABRACADABR

$ABRACADAB

BRA$ABRACA

BRACADABRA

CADABRA$AB

DABRA$ABRA

RA$ABRACAD

RACADABRA$

ADABRA$ABR

ABRA$ABRAC

A$ABRACADA

ACADABRA$A

$

A

A

A

A

A

B

B

C

D

R

R

A

R

D

$

R

C

A

A

A

A

B

B

The backward search algorithm efficiently finds occurrences of a pattern in a text using the LF-mapping

BWT matrix

Number

Number characters with the number of times they have appeard

F-column

L-column

We are dealing with enormous datasets

Reference genome sizes

- Homo sapiens: 3,200,000,000 bp

- Mus musculus: 2,700,000,000 bp

- Drosophila melanogaster: 140,000,000 bp

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: 12,000,000 bp

(~3.2 GB if using u8)

RNA-seq data

Contextualization

The best movie ever is only 1.2 GB

Most computers have 8 - 12 GB of RAM

ABRACADABRA$

ABRA

Suppose I want to find where

is located

1. Find rows with last character in search string (e.g., A) in F-column

2. Note which rows has the next letter (e.g., R) in L-column

3. Work backwards in search string until the first letter

A0

R0

D0

$

R1

C0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B1

B0

$

A0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B0

B1

C0

D0

R1

R0

A

R

ABRACADABR

$ABRACADAB

BRA$ABRACA

BRACADABRA

CADABRA$AB

DABRA$ABRA

RA$ABRACAD

RACADABRA$

ADABRA$ABR

ABRA$ABRAC

A$ABRACADA

ACADABRA$A

A0

R0

D0

$

R1

C0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B1

B0

$

A0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B0

B1

C0

D0

R1

R0

R

B

ABRACADABR

$ABRACADAB

BRA$ABRACA

BRACADABRA

CADABRA$AB

DABRA$ABRA

RA$ABRACAD

RACADABRA$

ADABRA$ABR

ABRA$ABRAC

A$ABRACADA

ACADABRA$A

A0

R0

D0

$

R1

C0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B1

B0

$

A0

A1

A2

A3

A4

B0

B1

C0

D0

R1

R0

B

A

ABRACADABR

$ABRACADAB

BRA$ABRACA

BRACADABRA

CADABRA$AB

DABRA$ABRA

RA$ABRACAD

RACADABRA$

ADABRA$ABR

ABRA$ABRAC

A$ABRACADA

ACADABRA$A

Backward search enables efficient searching using only first and last columns of BWT

BWT practice

Given the string "mississippi$", complete the following tasks:

- Construct the Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) of the string.

- Use the LF-mapping to find the number and positions of occurrences of the following patterns in the original string:

- a) "si"

- b) "iss"

- c) "pp"

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Splice-aware mapping with seed-chain-extend strategy

Seed-and-extend in hash-based alignment

Seed

Extend

Read: ATCGATTGCA

k-mers (k=3)

ATC, TCG, CGA, GAT, ATT, TTG, TGC, GCA

Use hash table for rapid lookup of potential matches quickly

Start from seed match and grow in both directions with reference genome

CCGTATCGATTGCAGATG

GAT

[7, 14]

h(k)

Check to see if we can align the read to reference

Before the next class, you should

Lecture 07A:

Quantification -

Foundations

Lecture 06B:

Sequence alignment -

Methodology

Today

Tuesday

Quiz 02

N

A

N

B

$

A

A

A

A

A

$

B

N

N

A

A

A

$

B

N

N

N

A

N

B

$

A

A

AN

AN

A$

$B

BA

NA

NA

AN

AN

A$

$B

BA

NA

NA

N

A

N

B

$

A

A

ANA

ANA

A$B

$BA

BAN

NAN

NA$

ANA

ANA

A$B

$BA

BAN

NAN

NA$

N

A

N

B

$

A

A

BWT output is reversible!

ANAN

ANA$

A$BA

$BAN

BANA

NANA

NA$B

BANANA$

NANA$BA

NA$BANA

A$BANAN

$BANANA

ANANA$B

ANA$BAN

- Write BWT output "vertically"

- Sort each row starting from the left-most character

- Append the same BWT output

- Repeat until finished (length of rows equal BWT output length)

2

3

2

3

2

3

2

...

Hash functions convert labels to table indices

Index: We take the key, count how many characters are in it

Note: This is a bad hashing function since "Alex" and "John" would result in the same index

Example

len("James") = 5

James

883-234-1236

BIOSC 1540: L06B (Read mapping)

By aalexmmaldonado

BIOSC 1540: L06B (Read mapping)

- 253