Math Review For Asymmetric Crypto

Divisibility

means a divides b:

for some c.

Examples:

Prime Numbers

A number p is prime if the only

numbers that divide it are 1 and p itself.

First few:

The most important thing about prime numbers is that they are building blocks of the integers.

Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic

All numbers can be written uniquely as a product of prime numbers.

Examples:

This is not true when composite numbers are involved:

Greatest Common Divisor (GCD)

The GCD of two numbers is the largest number that divides both of them.

If the GCD is 1, the two numbers are said to be coprime or relatively prime.

Examples:

Calculating the GCD

can be done very efficiently,

even without knowing the factorizations

of the numbers themselves!

Solving

Given two integers a and b, the Euclidean algorithm will produce the GCD as well as two integers u and v that solve the above.

def egcd(a,b):

"""Extended GCD algorithm"""

if b == 0:

return (a, 1, 0)

else:

g, x, y = egcd(b, a%b)

u = y

v = x - (a/b)*y

assert a*u + b*v == g

GCD = namedtuple('GCD', 'gcd u v')

return GCD(gcd = g, u = y, v = x - (a/b)*y)

print egcd(18,24)

$ python gcd.py

GCD(gcd=6, u=-1, v=1)Congruences: Modular arithmetic

means a - b is divisible by m.

Or: a and b differ only by a multiple of m.

Examples:

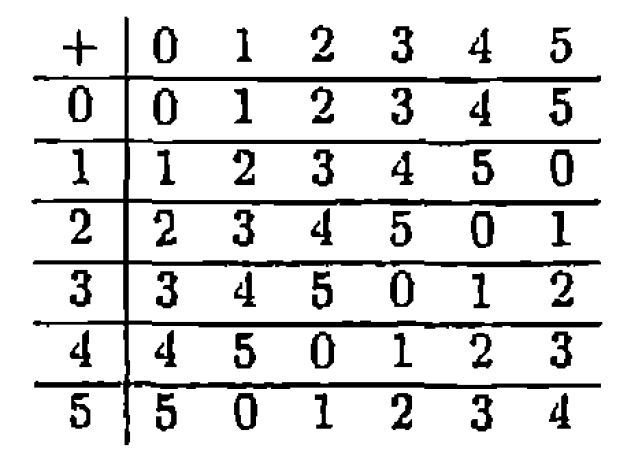

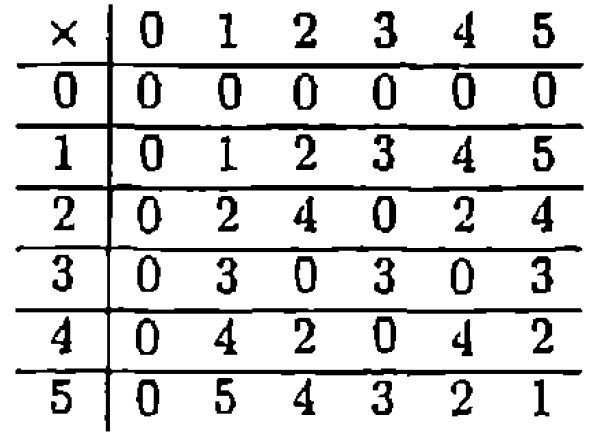

Addition and Multiplication mod p

The set of numbers mod p is often written

Addition in

Multiplication in

Division in

Let's say you want to solve for x:

This has a unique answer if and only if

Example:

Brute-force guessing gives:

Using the Euclidean Algorithm to find Inverses in

Thus 1583 and 7918 are coprime, and we can use Euclid's algorithm.

def invmod(a, m):

assert gcd(a,m) == 1

g = egcd(a,m)

result = g.u

# find the smallest positive solution

while result < 0:

result += m

return result

$ python invmod.py

5277

>>> (5277 * 1583) % 7918

1Modular inverse example

Chinese Remainder Theorem

Suppose x = 25 mod 42.

This means x = 25 + 42*k for some integer k.

This means x = 25 + 6*(7k) = 25 + 6m for some m. So x = 1 mod 6. Also,

x = 25 + 7*(6k) = 25 + 7n for some n. So x = 4 mod 7.

The CRT says this process can be reversed if m and n are coprime.

Big numbers:

Modular exponentiation

In crypto, calculating these numbers raised to large powers happens all the time. Here's an example of the algorithm.

Let's calculate:

Notice how each subsequent term involves squaring the previous one (sometimes multiple times)

Write the exponent in binary.

Then reading the bits from right to left, you can build a table of intermediate products, taking mods at each step.

def expmod(g, A, m):

bits = bin(A)[2:][::-1]

a = []

for i, bit in enumerate(bits):

a.append(g%m)

g = (g%m) * (g%m)

res = 1

for i, bit in enumerate(bits):

res *= a[i]**(int(bit)) % m

res %= m

return res

print expmod(3, 218, 1000)

$ python expmod.py

489"Fast Powering"

In Python, the "pow" function

does this for you, likely faster!

Fermat's Theorem

Here, p is a prime number, and doesn't divide a.

Example: let a = 2, and

Thus we know the number is composite!

(But no idea what its factors are)

Primitive Roots

Let

Thus 3 generates all the nonzero members of this set.

We call 3 a primitive root.

Public-Key Cryptosystem

In 1976, Diffie and Hellman came up with defined a PKC and trapdoor information.

Domain

Range

Easy!

Very difficult!

Easy, with some trapdoor information!

is a one-way function, easy to compute in one direction, very hard to invert without special information.

Are there truly one-way functions?

No one has concluded for sure that they exist. What we do have are several problems that people believe are very hard. Decades of trying to break them have failed--so far.

Two very common cryptosystems in use today depend on hard problems:

RSA: integer factorization problem

ECDH (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman): discrete log problem (DLP)

Today we focus only on the DLP.

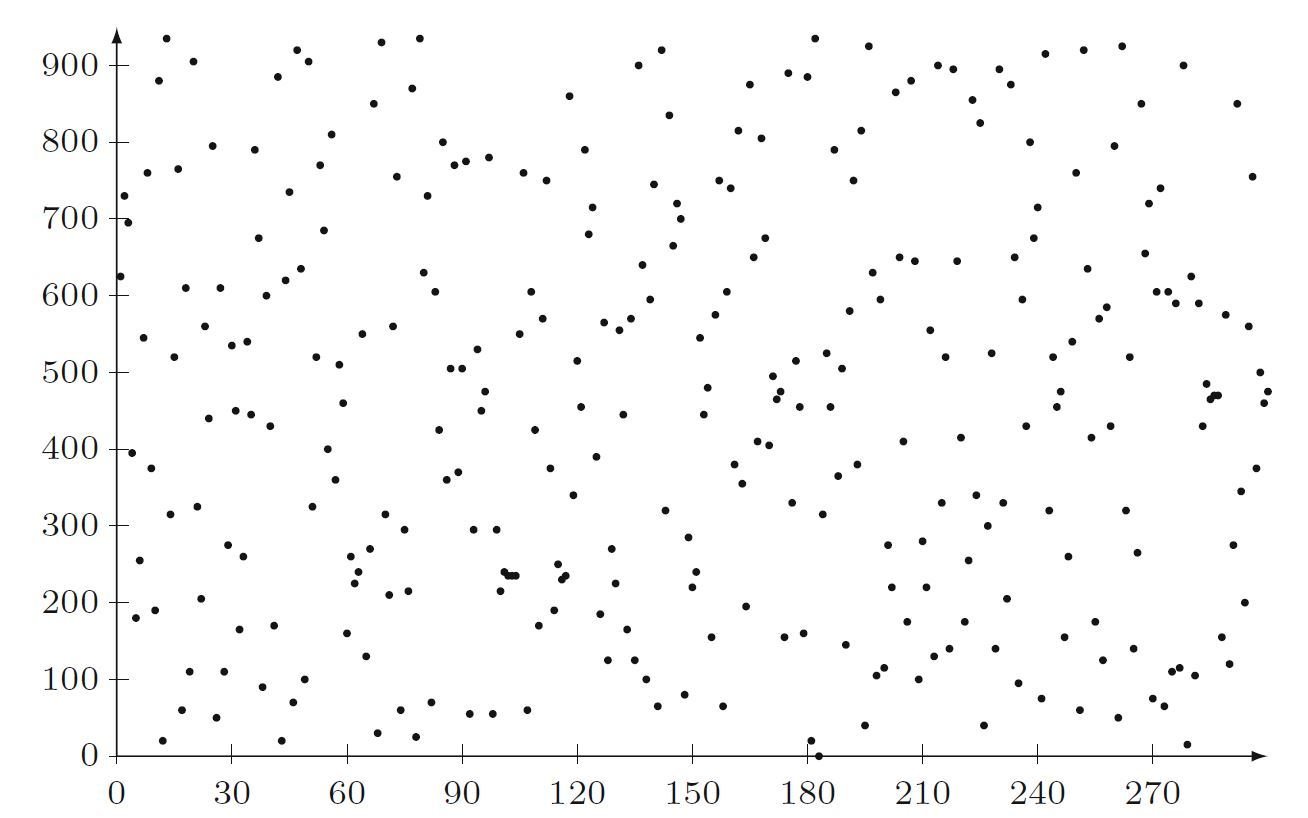

The Discrete Log Problem

Let p be a prime number. Then

Every element of

has an inverse, mod p.

You can prove that there is a primitive root g in this set. This means that g generates the set:

Let g be a primitive root for

Let h be an element of

Find x such that:

Discrete Logs Look Random

Diffie-Hellman Exchange

Step 0: Pick a (large) p and a primitive root g.

Step 1: Alice picks a secret integer a mod p and computes:

Step 2: Bob picks a secret integer b mod p and computes:

Step 3: Alice sends A to Bob. Bob sends B to Alice.

Step 4: Alice and Bob can compute a shared secret:

Eve's Hacking Challenge, mod p

She knows:

She wants:

This is the Diffie-Hellman Problem (DHP).

It is certainly no harder than the DLP.

If she solves the DLP (which is really difficult to solve) and gets a and b, she can solve the DHP.

If she solves the DHP, can she solve the DLP?

No one knows!

This problem is unfeasible to crack brute-force if

Key Exchange Example

Alice and Bob agree to use p = 941 and primitive root g = 627. This information is public. Even Eve knows it.

Alice chooses a secret key, 347. Bob chooses a secret 781.

Alice computes:

Bob computes:

Alice sends A to Bob. Bob sends B to Alice. Eve can see all this.

Alice and Bob can compute a shared secret key:

Breaking Lame Crypto: Pohlig-Hellman Theorem

The prime number you choose has to be very large, but that's not all.

Let's say p-1 factors into a product of "small" prime numbers.

Then for each small prime number r, I have a set of numbers:

generates

Eve gives this small generator to Bob, who computes a number

Now solve for each small factor.

Then stitch together x from all the x_i using the CRT!

Public-key crypto

By chrislambda

Public-key crypto

- 952