Preferences and Utility

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

Econ 50: Lecture 4

🐟

🥥

Production Possibilities Fronier

Feasible

Lecture 3: Resource Constraints

Lecture 2: Production Functions

Labor

Fish

🐟

Capital

Coconuts

🥥

[GOODS]

⏳

⛏

[RESOURCES]

🐟

🥥

🙂

😀

😁

😢

🙁

Today: Preferences

How does Chuck rank

all possible combinations

of fish and coconuts?

Goal: find the best combination within his production possibilities set.

Feasible

Today's Agenda

Part 1: Modeling Preferences with Utility Functions

Part 2: Some "canonical" utility functions

Preferences: Definition and Axioms

Indifference curves

The Marginal Rate of Substitution

Utility Functions

Perfect Substitutes

Perfect Complements

Cobb-Douglas

Quasilinear

Preferences

Preferences: Ordinal Ranking of Options

Given a choice between option A and option B, an agent might have different preferences:

The agent strictly prefers A to B.

The agent strictly disprefers A to B.

The agent weakly prefers A to B.

The agent weakly disprefers A to B.

The agent is indifferent between A and B.

Sidebar: “Strictly" vs. “Weakly"

The agent strictly prefers A to B.

The agent weakly prefers A to B.

Preference Axioms

Complete

Transitive

Any two options can be compared.

If \(A\) is preferred to \(B\), and \(B\) is preferred to \(C\),

then \(A\) is preferred to \(C\).

Together, these assumptions mean that we can rank

all possible choices in a coherent way.

Special case: choosing between bundles

containing different quantities of goods.

Preferences over Quantities

Example: “good 1” is apples, “good 2” is bananas, and “good 3” is cantaloupes:

🍏🍏🍏🍏

🍌🍌🍌

🍈🍈🍈🍈🍈🍈

🍏🍏🍏

🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍈🍈

General framework: choosing between anything

Special Case: Two Goods

Good 1 \((x_1)\)

Good 2 \((x_2)\)

Completeness axiom:

any two bundles can be compared.

Implication: given any bundle \(A\),

the choice space may be divided

into three regions:

preferred to A

dispreferred to A

indifferent to A

Indifference curves cannot cross!

Marginal Rate of Substitution

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍏🍏

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌

Suppose you were indifferent between the following two bundles:

Starting at bundle X,

you would be willing

to give up 4 bananas

to get 2 apples

Let apples be good 1, and bananas be good 2.

Starting at bundle Y,

you would be willing

to give up 2 apples

to get 4 bananas

Visually: the MRS is the magnitude of the slope

of an indifference curve

Utility Functions

How do we model preferences mathematically?

Approach: assume consuming goods "produces" utility

Production Functions

Labor

Fish

🐟

Capital

⏳

⛏

[RESOURCES]

Utility Functions

Utility

😀

[GOODS]

Fish

🐟

Coconuts

🥥

Representing Preferences with a Utility Function

"A is strictly preferred to B"

Words

Preferences

Utility

"A is weakly preferred to B"

"A is indifferent to B"

"A is weakly dispreferred to B"

"A is strictly dispreferred to B"

Suppose the "utility function"

assigns a real number (in "utils")

to every possible consumption bundle

We get completeness because any two numbers can be compared,

and we get transitivity because that's a property of the operator ">"

Marginal Utility

Given a utility function \(u(x_1,x_2)\),

we can interpret the partial derivatives

as the "marginal utility" from

another unit of either good:

Indifference Curves and the MRS

Along an indifference curve, all bundles will produce the same amount of utility

In other words, each indifference curve

is a level set of the utility function.

The slope of an indifference curve is the MRS. By the implicit function theorem,

(Note: we'll treat this as a positive number, just like the MRTS and the MRT)

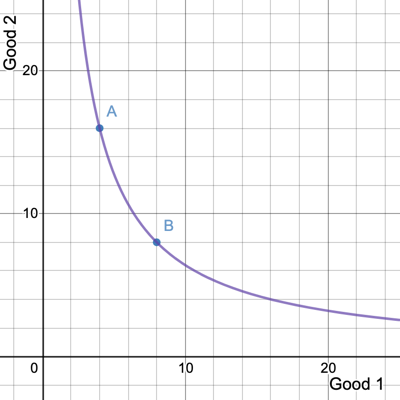

A

B

Do we have to take the

number of "utils" seriously?

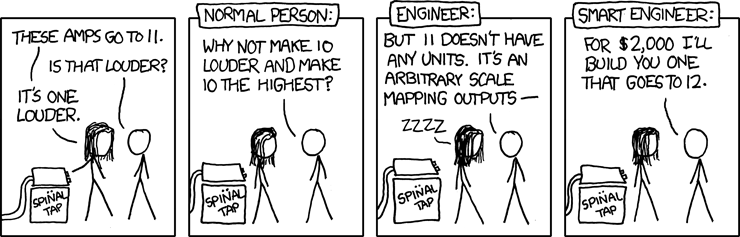

From XKCD:

Just like the "volume" on an amp, "utils" are an arbitrary scale...saying you're "11" happy from a bundle doesn't mean anything!

All we want to use utility functions for

is to describe preference orderings.

It doesn't matter that “utils" are nonsense.

As long as the utility function generates the correct indifference map,

it doesn't matter what the level of utility at each indifference curve is.

Transforming Utility Functions

Applying a positive monotonic transformation to a utility function doesn't affect

the way it ranks bundles.

Example: \(\hat u(x_1,x_2) = 2u(x_1,x_2)\)

Transformations and the MRS

Applying a positive monotonic transformation to a utility function doesn't affect

its MRS at any bundle (and therefore generates the same indifference map).

Example: \(\hat u(x_1,x_2) = 2u(x_1,x_2)\)

Transformations and the MRS

Applying a positive monotonic transformation to a utility function doesn't affect

its MRS at any bundle (and therefore generates the same indifference map).

Example: \(\hat u(x_1,x_2) = \ln(u(x_1,x_2))\)

Normalizing Utility Functions

One reason to transform a utility function is to normalize it.

This allows us to describe preferences using fewer parameters.

[ multiply by \({1 \over a + b}\) ]

[ let \(\alpha = {a \over a + b}\) ]

Desirable Properties of Preferences

We've asserted that all (rational) preferences are complete and transitive.

There are some additional properties which are true of some preferences:

- Monotonicity

- Convexity

- Continuity

- Smoothness

Monotonic Preferences: “More is Better"

Nonmonotonic Preferences and Satiation

Some goods provide positive marginal utility only up to a point, beyond which consuming more of them actually decreases your utility.

Strict vs. Weak Monotonicity

Strict monotonicity: any increase in any good strictly increases utility (\(MU > 0\) for all goods)

Weak monotonicity: no increase in any good will strictly decrease utility (\(MU \ge 0\) for all goods)

Example: Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine has a dose of 0.3mL, Moderna's has a dose of 0.5mL

Goods vs. Bads

Convex Preferences: “Variety is Better"

Math background: "Convex combinations"

Convex Preferences: “Variety is Better"

Take any two bundles, \(A\) and \(B\), between which you are indifferent.

Would you rather have a convex combination of those two bundles,

than have either of those bundles themselves?

If you would always answer yes, your preferences are convex.

Concave Preferences: “Variety is Worse"

Take any two bundles, \(A\) and \(B\), between which you are indifferent.

Would you rather have a convex combination of those two bundles,

than have either of those bundles themselves?

If you would always answer no, your preferences are convex.

Common Mistakes about Convexity

1. Convexity does not imply you always want equal numbers of things.

2. It's preferences which are convex, not the utility function.

Other Desirable Properties

Continuous: utility functions don't have "jumps"

Smooth: marginal utilities don't have "jumps"

Counter-example: vaccine dose example

Counter-example: Leontief/Perfect Complements utility function

Well-Behaved Preferences

If preferences are strictly monotonic, strictly convex, continuous, and smooth, then:

Indifference curves are smooth, downward-sloping, and bowed in toward the origin

The MRS is diminishing as you move down and to the right along an indifference curve

Good 1 \((x_1)\)

Good 2 \((x_2)\)

"Law of Diminishing MRS"

Summary of Part I

Part I: properties of preferences,

and how preferences can be represented by utility functions.

Part II: see examples of utility functions,

and examine how different functional forms

can be used to model different kinds of preferences.

Take the time to understand this material well.

It's foundational for many, many economic models.

Econ 50 | 4 | Preferences and Utility

By Chris Makler

Econ 50 | 4 | Preferences and Utility

- 736