The Library Astronomers Need

Daina Bouquin

Fundamentally, what do libraries do?

Provide shared resources to help their communities create and share new knowledge.

New resources are needed to:

- address big data needs

- enable the creation and preservation of

non-traditional scholarly work - undercut white supremacy and misogyny

What's a petabyte?

1 PB

1,048,576 GB

~13.3 years of HD video

1.5 PB

10 Billion Facebook photos

20 PB

amount of data processed by Google in a day

50 PB

estimated amount of written work created by mankind in all languages from the beginning of recorded history

Data collected from astronomical sky surveys has grown from gigabytes to petabytes throughout the past decade and is predicted to grow in the next decade into exabytes with new observatories coming into operation.

1,024 PB = 1 Exabyte

~237,823 years of HD video

Data doesn't stop being data

because it's old.

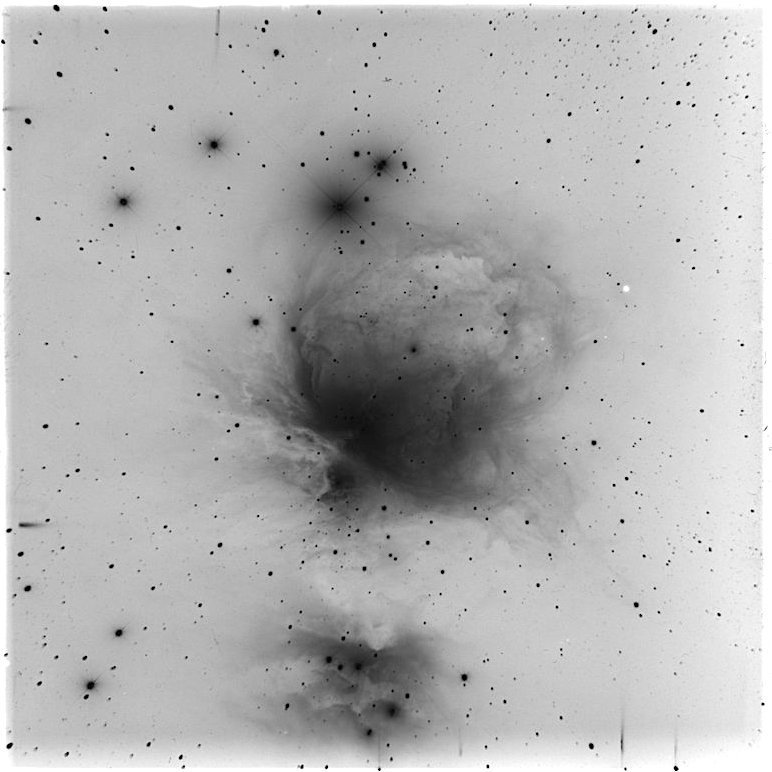

Harvard has over 550,000 glass plates, and there are millions of plates all over the world.

Incorporating legacy datasets into contemporary analyses will enable groundbreaking science, but new approaches are needed to make this data usable.

To address big data we need astroinformatics resources.

"informatics" = the discipline of organizing, accessing, integrating, and mining data from multiple sources for discovery and decision support.

"astroinformatics" = doing informatics in astronomy

We need someone to serve as a methodological and technical expert to the astronomy community by providing consultations and training in astroinformatics topics.

We need someone to design and implement high-quality, sustainable, open software to further innovative research using large historical astronomical datasets.

Why does it make sense to put this person in the library?

We need to an Astroinformatics Scientist

in the library.

LIBRARIANS ARE

INFORMATION SCIENTISTS

Master of Library and Information Science

The ADS is also in the Library and where else

would this person be if they need to help everyone?

Astronomy is so much more than big datasets.

Astronomy involves hardware, software, data, and people.

It isn't just astronomers interpreting data.

Software and hardware are scholarly objects.

By ignoring this we are watching our

astronomical legacy get lost to time.

We are also causing

a brain drain.

Early career researchers spend years up-skilling, (often teaching themselves and each other) how to develop software that can support astronomical analyses only to find their code isn't treated as part of their scholarship.

They can make more money and feel more valued outside of academia so they leave.

Hardware matters too.

We rely on instruments, but the engineers that create them are constantly dealing with problems caused by information fragmentation.

Specifications and prototypes end up lost in drives or stored closets and basements where valuable metadata about them never gets recorded, let alone shared.

This makes it hard for people to share lessons learned, build new collaborations, and learn from the past.

We can't just focus on archiving and analyzing data.

To enable the creation and preservation of non-traditional scholarly work we also need an Open Science Librarian.

We need someone who can support the adoption of open science practices and the development of relevant tools that can be incorporated into existing workflows used by instrumentalists and engineers.

We also need a Digital Preservationist to allow us to capture the born-digital and digitized objects that the community creates.

(It is impossible for us to do this at scale without another person.)

We can't ignore the fact that Astronomy is conducted by people.

People have flaws.

Colonialism, racism, chauvanism have been, and

continue to be, facets of astronomical pursuits.

From 1889 through 1927, the HCO operated a southern sky photography station in the Peruvian Andes.

This extension of the HCO was staffed by American astronomers and both Peruvian and Amerindian workers, but all astronomical photographs, and scientific prestige, were sent back to Cambridge.

HCO also used land seizures, water policy, and walls to impose labor regimes of race and gender that elevated the HCO's scientific reputation at the expense of national development in Peru.

A long-running and intensifying struggle exists between Native Hawaiʻians and astronomers over the use of Maunakea.

Thanks to U.S. imperialism and appropriation of Hawaiʻian lands in 1893, thirteen telescope complexes have been built there despite Native Hawaiʻian opposition.

Many astronomers who use data from telescopes on Maunakea view their work as inherently nonviolent and in the common interest of humanity.

Native Hawai’ians assert that their Indigenous rights to self-determination are being attacked while astronomers directly benefit from their disenfranchisement.

Bringing historical perspectives into conversations about the future of astronomy is the right thing to do.

This is a matter of practical urgency.

We cannot make astronomy welcoming to people who have been traditionally excluded from the field if we don't learn from the past.

We need to fully fund our

Historian-in-Residence Fellowship

This is currently a six-month position that's entirely reliant on the funding the Library hasn't used because we couldn't travel during the pandemic.

This fellowship goes away unless I can find external funding and that is not a strategic or thoughtful way to address these needs.

Astronomy is changing.

So much data will enable groundbreaking science, but it will also challenge researchers.

We can no longer justify dedicating all of our attention to traditional scholarly objects.

We need to learn from the past or we'll watch ourselves repeat it.

The Library needs to change too.

The Library Astronomers Need

By Daina Bouquin

The Library Astronomers Need

- 776