Digital Preservation at Dumbarton Oaks

How to Navigate this Course

Great!

What is Digital Preservation?

Why?

Why Does This Matter to Me?

What are the challenges in digital preservation?

Media Failure

The Lifespan of Storage Media

- CDs/DVDs: 2-20 years(!) - in good conditions

- Floppy disks: obsolete - most computers no longer have readers

- USBs: 10,000 writes

- Hard Drives: 3 years, then 12% annual failure rate

- External Hard Drives: Less time due to wear and tear

- CDs/DVDs: 2-20 years(!) - in good conditions

- Floppy disks: obsolete - most computers no longer have readers

- USBs: 10,000 writes

- Hard Drives: 3 years, then 12% annual failure rate

- External Hard Drives: Less time due to wear and tear

Physical Loss

An example of physical loss by

natural disaster.

- Poor storage environment

- Overuse

- Infrastructure failure / Inadequate maintenance

- Hardware failure or malfunction

- Natural disaster

- Human error

- Sabotage

File Format Obsolescence

- Proprietary software upgrades lead to a new format version, and the old format is no longer fully supported

- The software supporting a file format is no longer widely available

- The market is dominated by a new format (e.g., Microsoft Word's .doc/x has made other word processing formats obsolete)

- The format simply fails on the market, due to any number of reasons (e.g., unfixed bugs, poor usability)

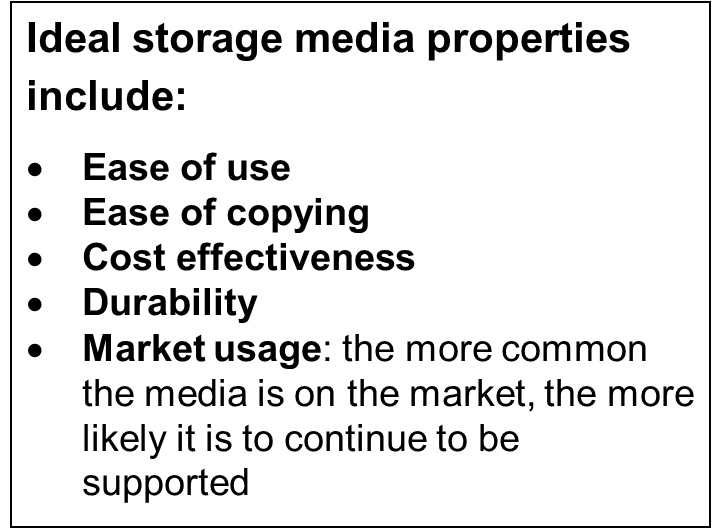

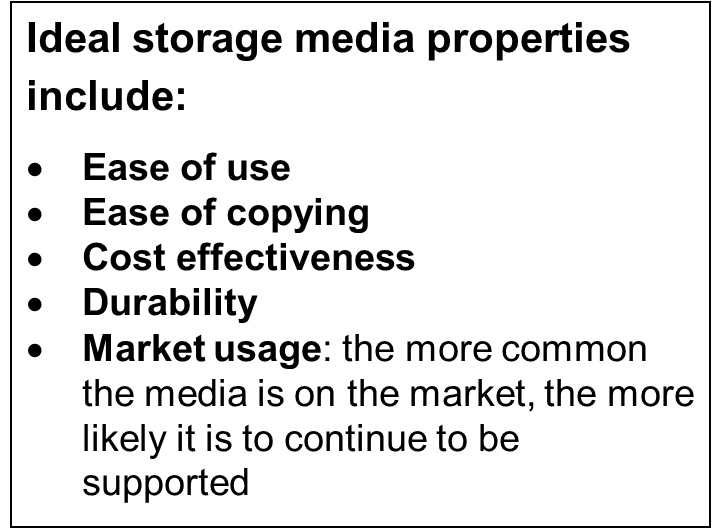

Media Format Obsolescence

What YOU Can Do

Migrate Files from Old Media

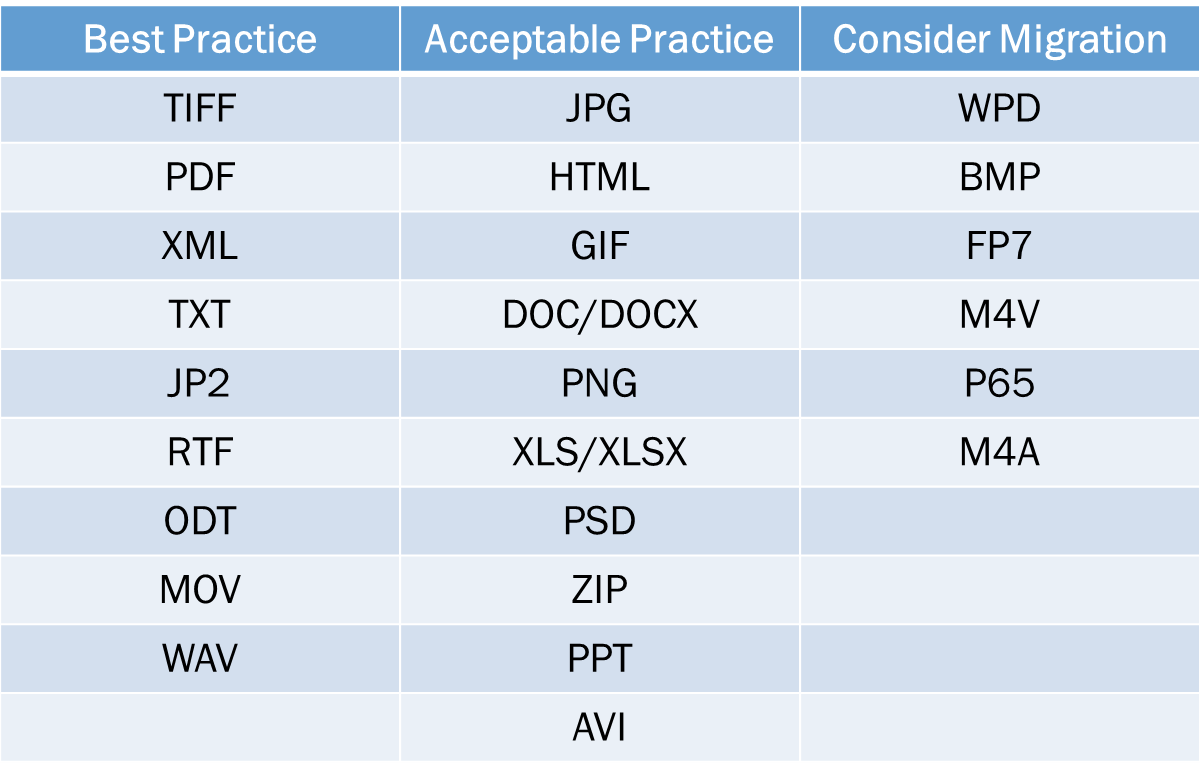

Choose the Right File Format

- Is it proprietary or open source? Proprietary formats often require software purchases, and are not updated as often to fix bugs. Open source formats are generally supported by freely-available software and are updated by a community of users.

- Is the format widely used?

- Are older versions of the format still readable? This suggests that a format has backward compatibility.

- Does it support your needs?

Make Your Digital Files Findable

- Keep it short.

- Add structural elements that will help you locate the file

- Only use underscores (_) and hyphens (-)

- Order information by importance

Archive Your Email

Email messages often contain pertinent information about departmental and institutional work. They can contain project- or collection-related information that needs to be preserved.

- Identify messages that have long-term value

- Export selected messages- save in a recommended format such as PDF

- Organize messages for findability- save with related project or collection if possible

- Identify messages that have long-term value

- Export selected messages- save in a recommended format such as PDF

- Organize messages for findability- save with related project or collection if possible

Ensure the Security of Your Information

- Ensure that no single user has access to all redundant copies of important digital files

- Immediately remove users after staff turnover

- Maintain a comprehensive list of users and permissions

Managing Digital Assets

What are Digital Assets?

Digital Assets vs. Everyday Files

Just as you title your files to ensure findability, it is important to also separate the most important files, digital assets, from the everyday files with no enduring value. This is because digital assets require different digital preservation steps and need to be easily identified. It is also important to separate them in order to prevent any accidental deletion of important files.

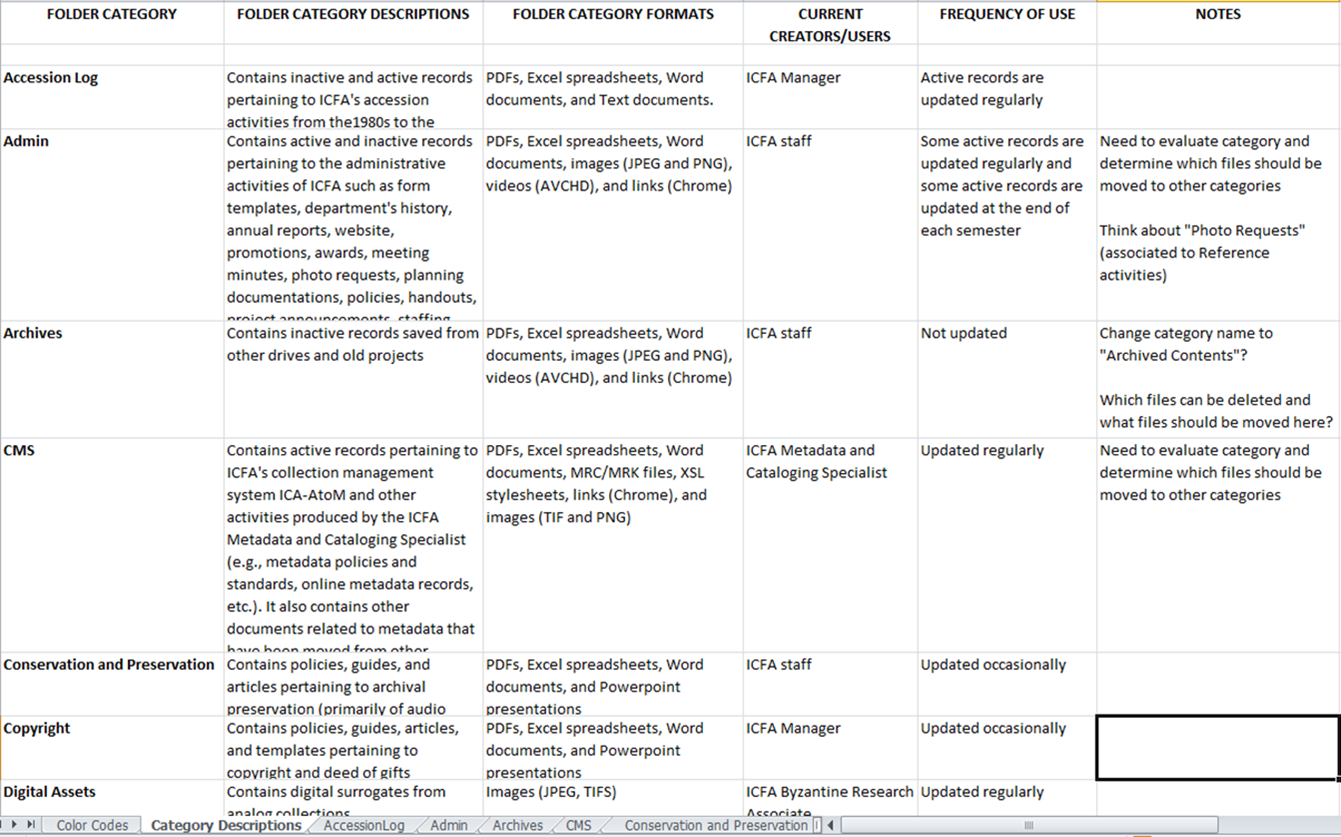

Create a Comprehensive Inventory

In order to keep track of your digital assets, it is important to create a comprehensive inventory of the files, their formats, and their locations.

This can be done manually, but there are also specific tools- such as <DROID>- that will carry out the inventory much more quickly. The inventory should be carried out yearly (or as needed within the institution/department).

A file-level inventory will assist in carrying out other activities related to digital asset preservation.

Implement File Format Restrictions

To make your digital assets easily manageable, it is important to maintain them in only a few file formats. By implementing file format restrictions, you can also ensure that your collections follow the best practices suggested for each media type. For more information, see JISC's <Digital Media guides>.

To determine the best file formats to use, you can also refer to the criteria explained in the previous section.

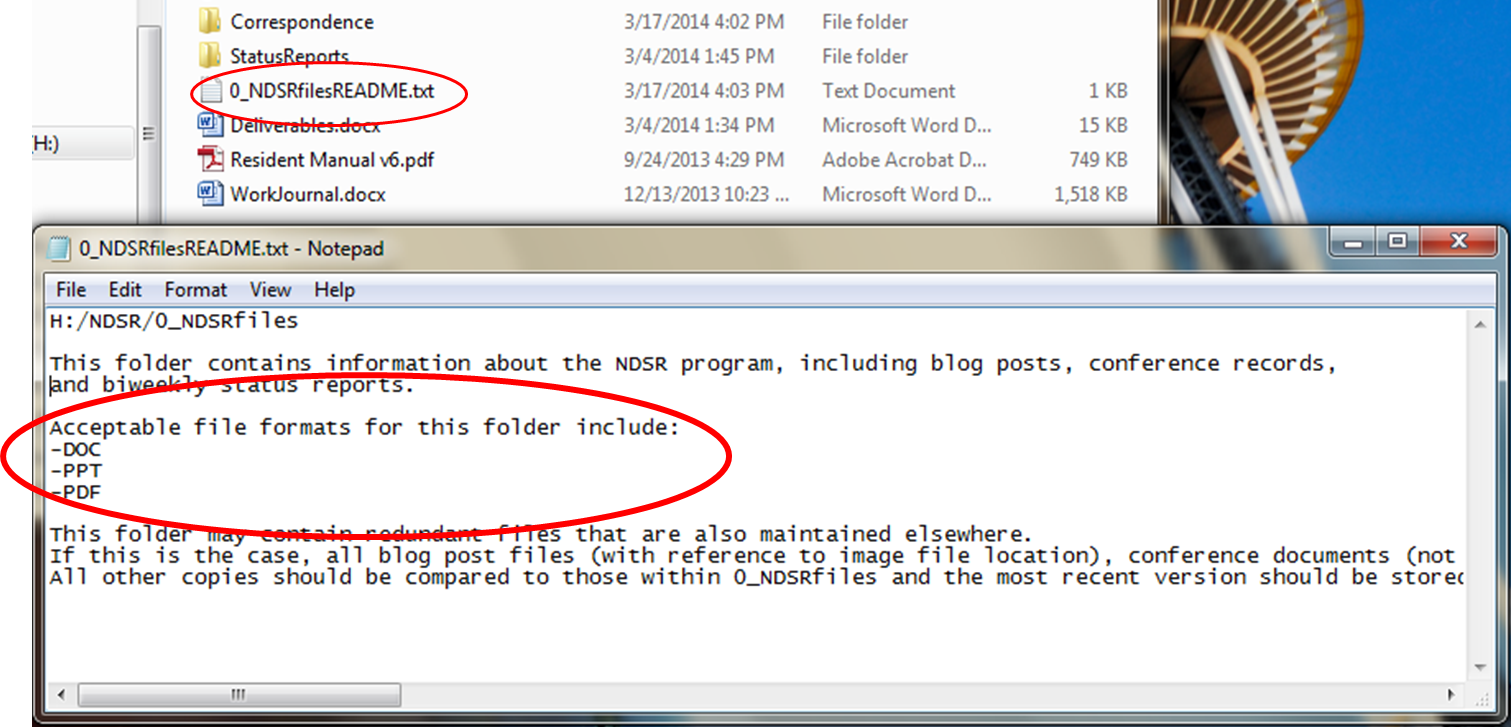

Implement Format Restrictions

An example of file format restrictions, as defined in a simple TXT document, called a README file, saved within the project folder.

Migrate Files into Selected Formats

Migrate Files into Selected Formats, Cont.

Maintain Redundant Copies

Maintain Redundant Copies

Check File Fixity

To ensure the continued readability of files, a checksum should be generated on ingest (addition to the repository) of each digital asset. A checksum is a number representing the sum of digits in a piece of data, against which later comparisons can be made in order to detect any data loss or change.

Potential fixity tools can be found here:

<http://digitalpowrr.niu.edu/tool-grid/>

Check File Fixity, Cont.

Metadata

In order to be useable and useful, a digital asset should include as much descriptive information, or metadata, as possible. This includes the checksum described in the previous slide, as well as information like:

- original filename, location, and other administrative metadata;

- technical metadata describing the file structure; and

-

copyright information.

Some administrative metadata can be automatically generated using settings on the original device. Pertinent metadata should be saved redundantly to a project log.

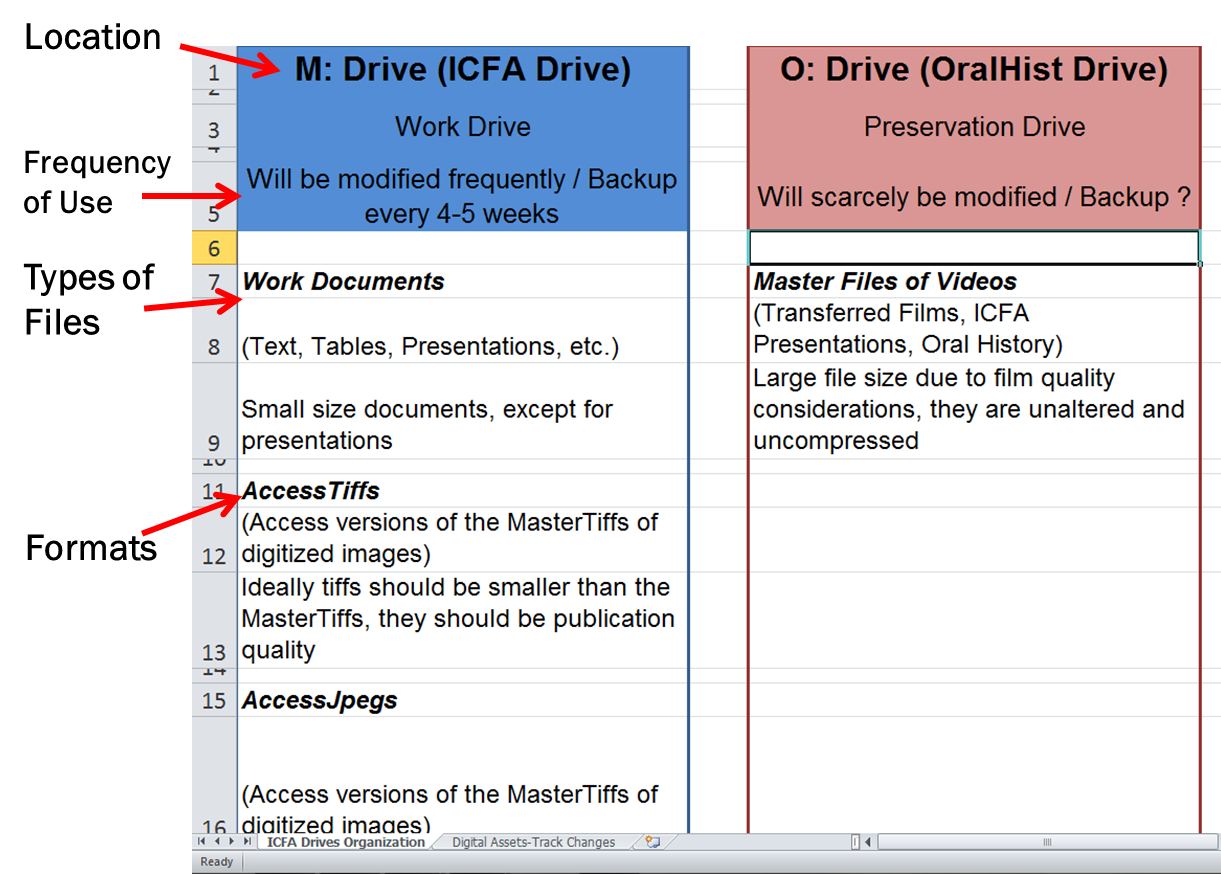

Document Your Storage Plan

Document Your Storage Plan, Cont.

An example of a retention schedule.

Retention schedules can also include more detail, depending on the collection and its potential users.

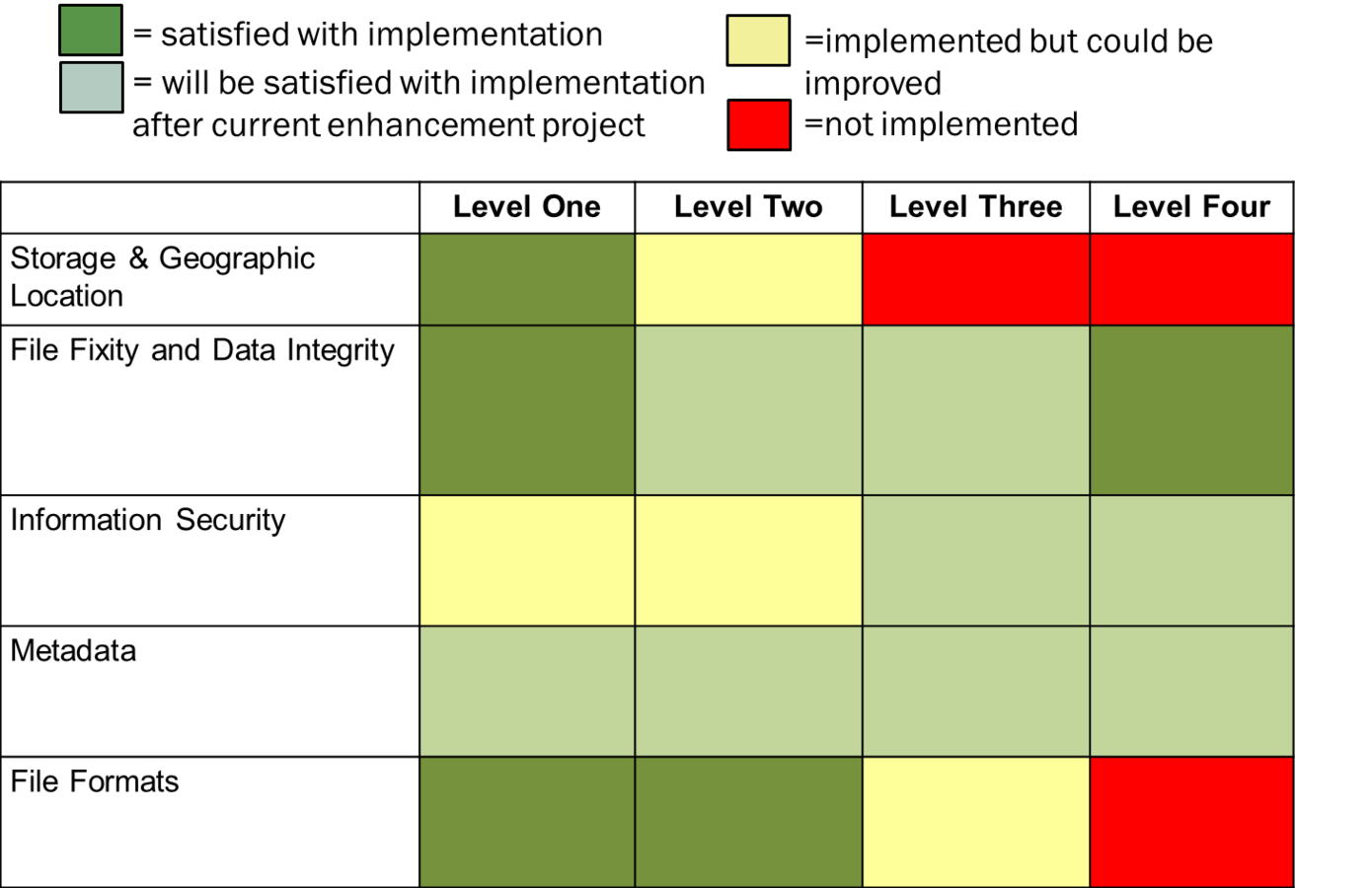

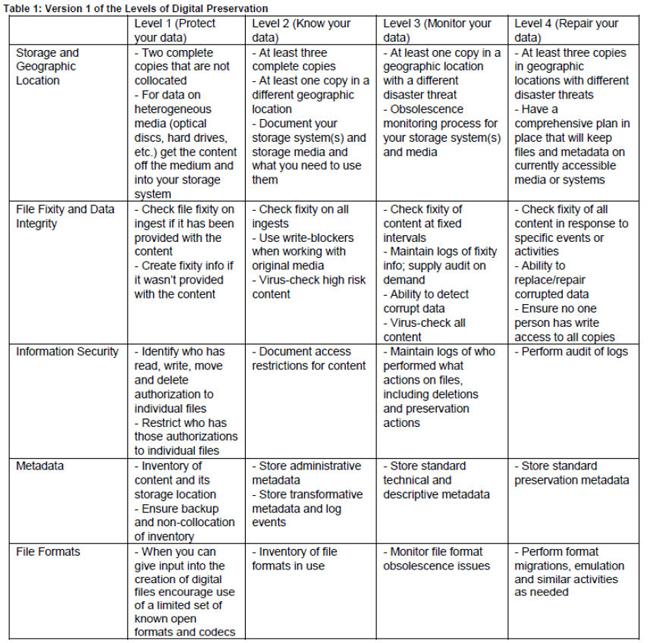

National Digital Stewardship Alliance

Levels of Preservation

http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/ndsa/activities/levels.html

The NDSA Levels of Preservation

Self Assessment Example

How Do You Measure Up?

The Current Landscape at Dumbarton Oaks

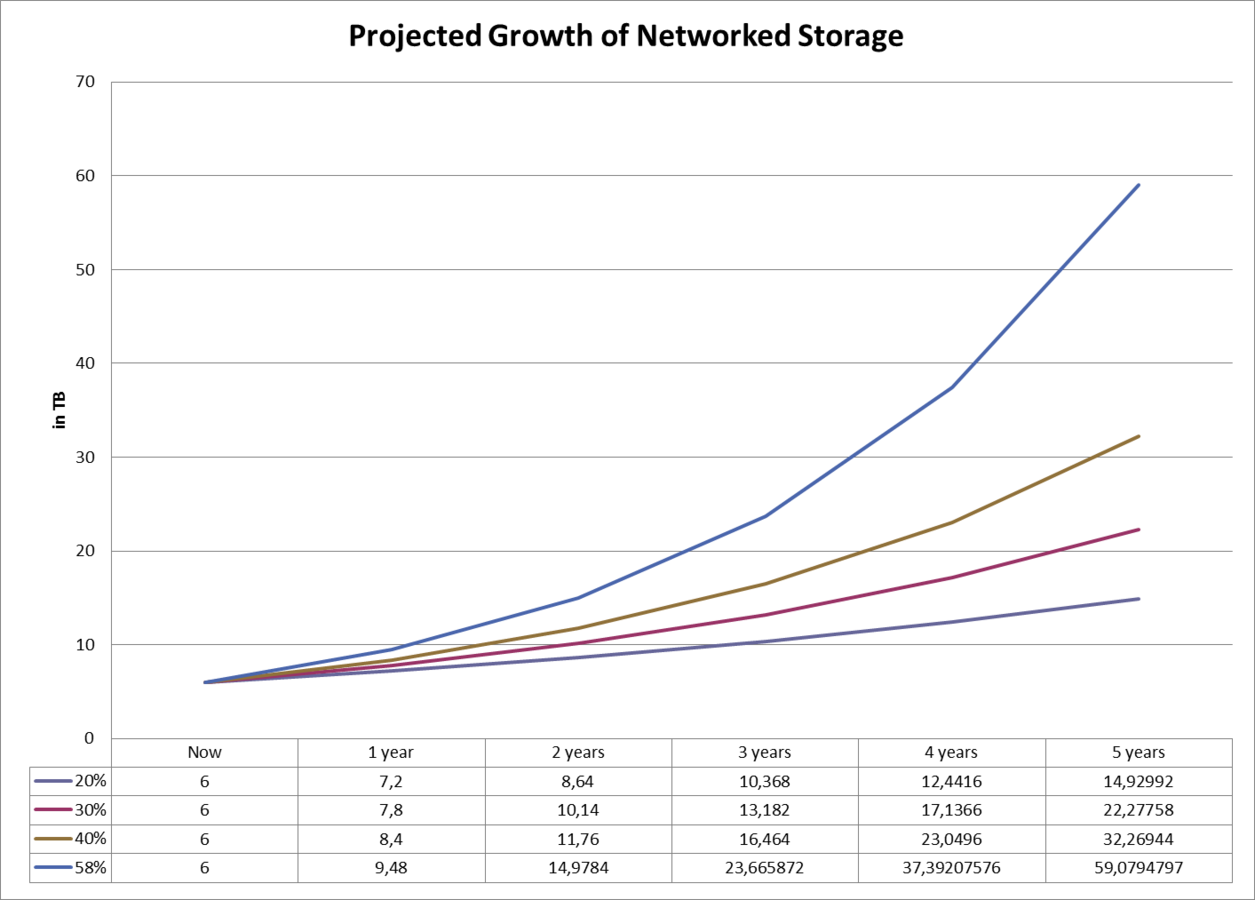

Storage and Geographic Location

Currently, Dumbarton Oaks' storage capacity is somewhere around 25 TB. This chart indicates that digital storage needs could potentially outgrow the institution's capacity within 3-5 years if non-strategic growth continues.

File Formats

This information comes from a file-level inventory that was undertaken on most of the institution's networked storage in Fall 2013.

There are currently 274 file formats in use around the institution. While the most-used formats, like TIFF and JPG, are non-proprietary and considered best practices, some of these formats are proprietary and/or outdated.

File Fixity and Data Integrity

Metadata

Information Security

Specific Recommendations for Dumbarton Oaks

Back Up Your Data!

Shared (H:/) Drive - Nightly

User (G:/) Drive – Nightly

Email Archive Drive - Nightly

Departmental Drives – Generally Monthly*

*Consult the IT Department for information on specific drives.

Backups In the Cloud...

- Distributed copies

- Easy access to files anywhere

- NOT good for primary long-term preservation storage

- Regularly weed unnecessary files to prevent overflow

Contact webhelp [at] doaks [dot] org for a user account

- Distributed copies

- Easy access to files anywhere

- NOT good for primary long-term preservation storage

- Regularly weed unnecessary files to prevent overflow

Sharing on the Intranet

Address File Format Issues

Top Formats at Dumbarton Oaks

Fix File Fixity

Standardize Metadata Within Each Department

Secure Your Data

In Sum...

Image Credit

All images are licensed under Creative Commons.

Digital Preservation at Dumbarton Oaks

By Heidi Dowding

Digital Preservation at Dumbarton Oaks

Slides adapted from a March 2014 workshop at Dumbarton Oaks.

- 2,640