Lecture 21:

More Limit Theorems

Arithmetic operations on sequences

Given two sequences \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) we define the following sequences:

\[X+Y:=(x_{n}+y_{n})\]

\[X-Y:=(x_{n}-y_{n})\]

\[X\cdot Y:=(x_{n}y_{n})\]

If \(c\in\R\) then

\[cX:=(cx_{n})\]

If \(y_{n}\neq 0\) for all \(n\in\N\) then we set

\[X/Y: = \left(\frac{x_{n}}{y_{n}}\right)\]

Examples

If we have

\[X = (3, 7, 11, 15, \ldots, 4n-1,\ldots)\quad\text{and}\quad Y = \left(0, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{2}{3},\ldots,\frac{n-1}{n},\ldots\right)\]

Then

\[X+Y = \left(3,\frac{15}{2},\frac{35}{3},\ldots,\frac{4n^2-1}{n},\ldots\right)\]

\[X-Y = \left(3,\frac{13}{2},\frac{31}{3},\ldots,\frac{4n^2-2n+1}{n},\ldots\right)\]

\[X\cdot Y = \left(0,\frac{7}{2},\frac{22}{3},\frac{45}{4},\ldots,\frac{(4n-1)(n-1)}{n},\ldots\right)\]

\[6Y = \left(0,3,4,\frac{9}{2},\ldots,\frac{6n-6}{n},\ldots\right)\]

Note that \(X/Y\) is not well defined, but \(Y/X\) is well defined.

STOP. What is the 10th term of the sequence \(Y/X\)?

\[Y/X = \left(0,\frac{1}{14},\frac{2}{33},\ldots,\frac{n-1}{4n^2-n},\ldots\right)\]

The \(10\)th term of \(Y/X\) is \(\frac{10-1}{4(10)^2-10} = \frac{9}{390} = \frac{3}{130}\)

Examples

If we have

\[X = (3, 7, 11, 15, \ldots, 4n-1,\ldots)\quad\text{and}\quad Y = \left(0, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{2}{3},\ldots,\frac{n-1}{n},\ldots\right)\]

Then

\[X+Y = \left(3,\frac{15}{2},\frac{35}{3},\ldots,\frac{4n^2-1}{n},\ldots\right)\]

\[X-Y = \left(3,\frac{13}{2},\frac{31}{3},\ldots,\frac{4n^2-2n+1}{n},\ldots\right)\]

\[X\cdot Y = \left(0,\frac{7}{2},\frac{22}{3},\frac{45}{4},\ldots,\frac{(4n-1)(n-1)}{n},\ldots\right)\]

\[6Y = \left(0,3,4,\frac{9}{2},\ldots,\frac{6n-6}{n},\ldots\right)\]

Let \(X=(x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers such that

\[\lim X = x\quad\text{and}\quad \lim Y=y.\]

What can we say about \(\lim(X+Y)\)?

We know that:

- \(\lim X = x\) implies that \(x_{n}\) is close to \(x\) for large \(n\).

- \(\lim Y = y\) implies that \(y_{n}\) is close to \(y\) for large \(n\).

We expect \(x_{n}+y_{n}\) to be close to \(x+y\). (And it is!)

We must show that

\[|(x_{n}+y_{n}) - (x+y)|\]

can be made as small as we like by taking \(n\) to be sufficiently large.

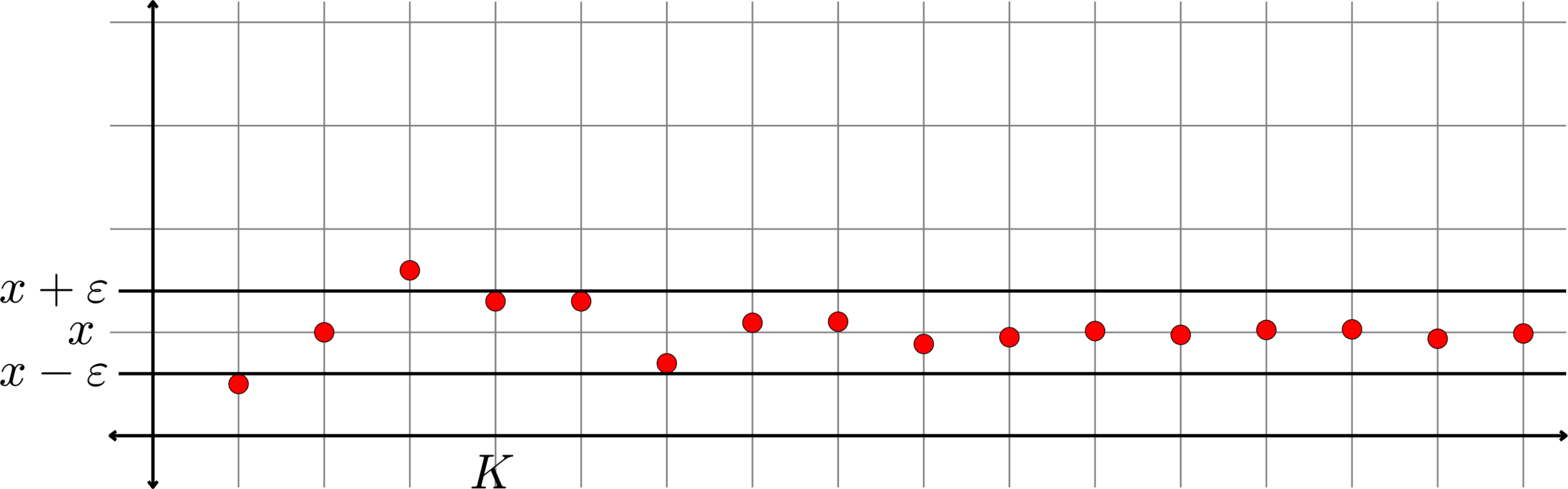

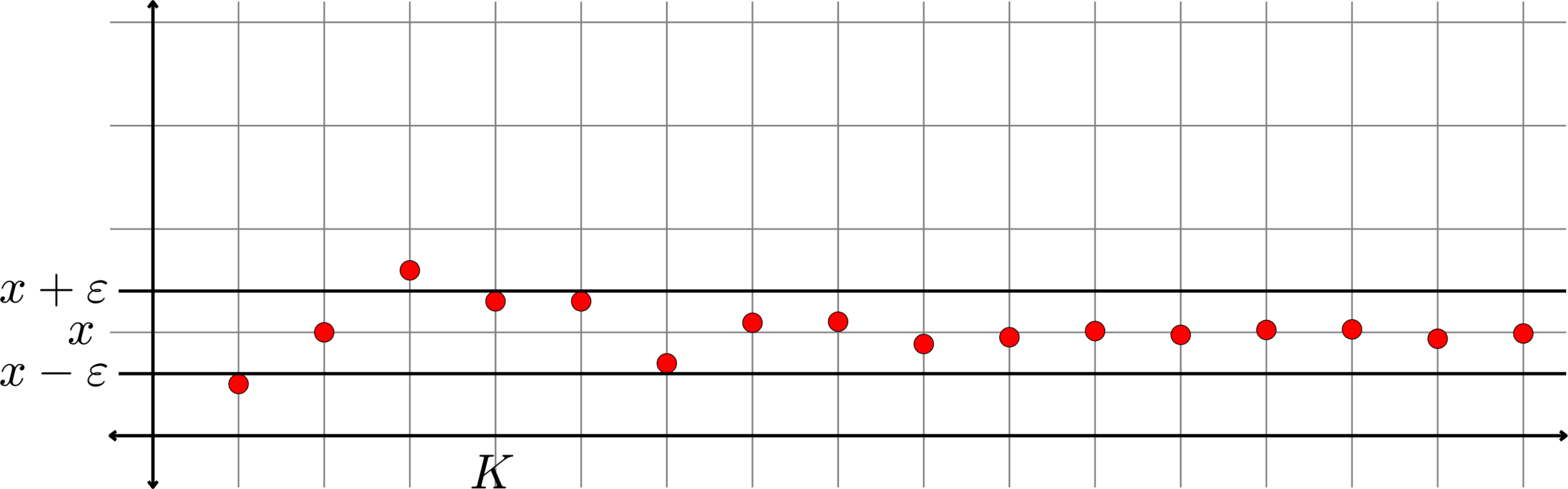

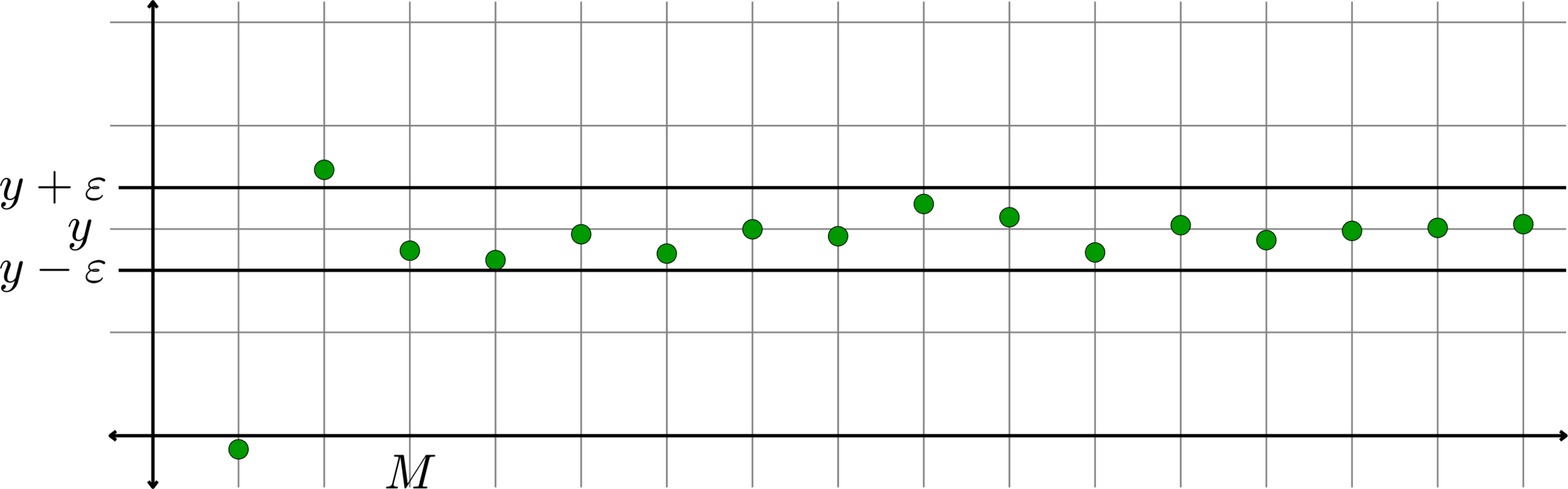

\(X=(x_{n})\)

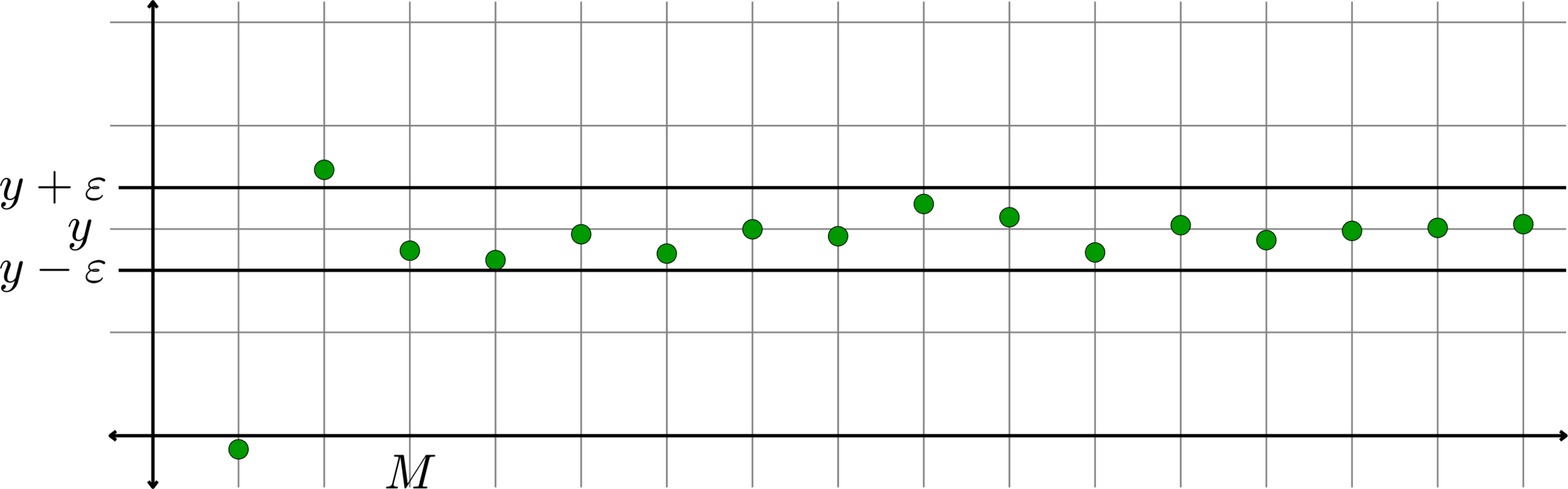

\(Y=(y_{n})\)

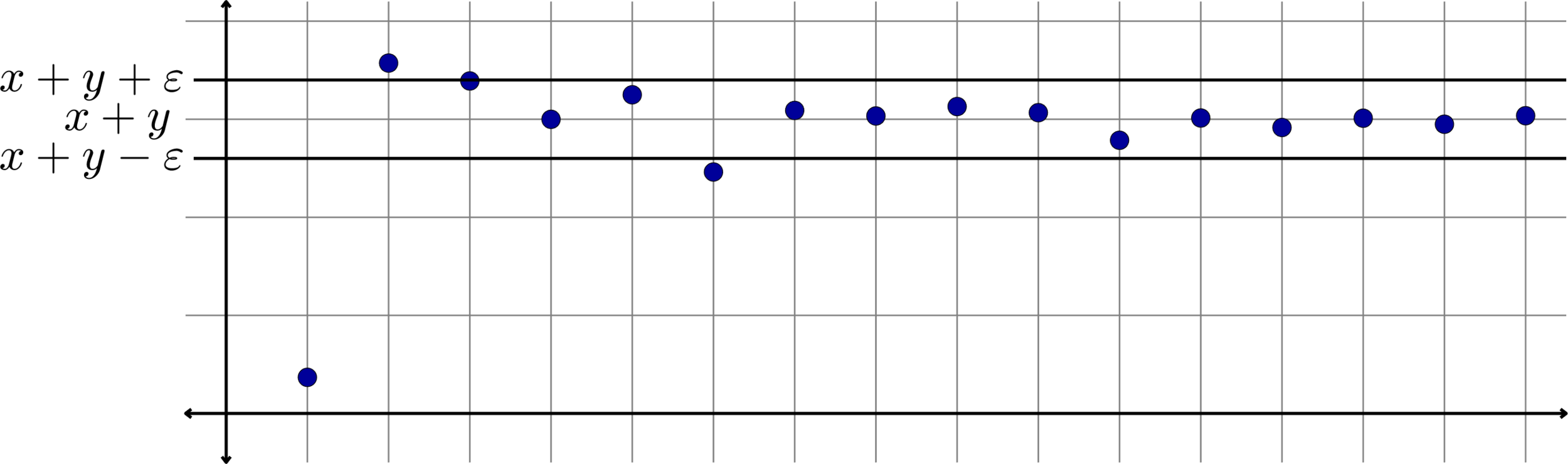

\(X+Y=(x_{n}+y_{n})\)

\(X=(x_{n})\)

\(Y=(y_{n})\)

\(X+Y=(x_{n}+y_{n})\)

Theorem 1. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X+Y\) has limit \(x+y\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. There exists a number \(K\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\text{ for all }n\geq K.\]

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. There exists a number \(K\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\text{ for all }n\geq K.\]

There also exists a number \(M\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\text{ for all } n\geq M.\]

Theorem 1. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X+Y\) has limit \(x+y\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. There exists a number \(K\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\text{ for all }n\geq K.\]

There also exists a number \(M\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\text{ for all } n\geq M.\]

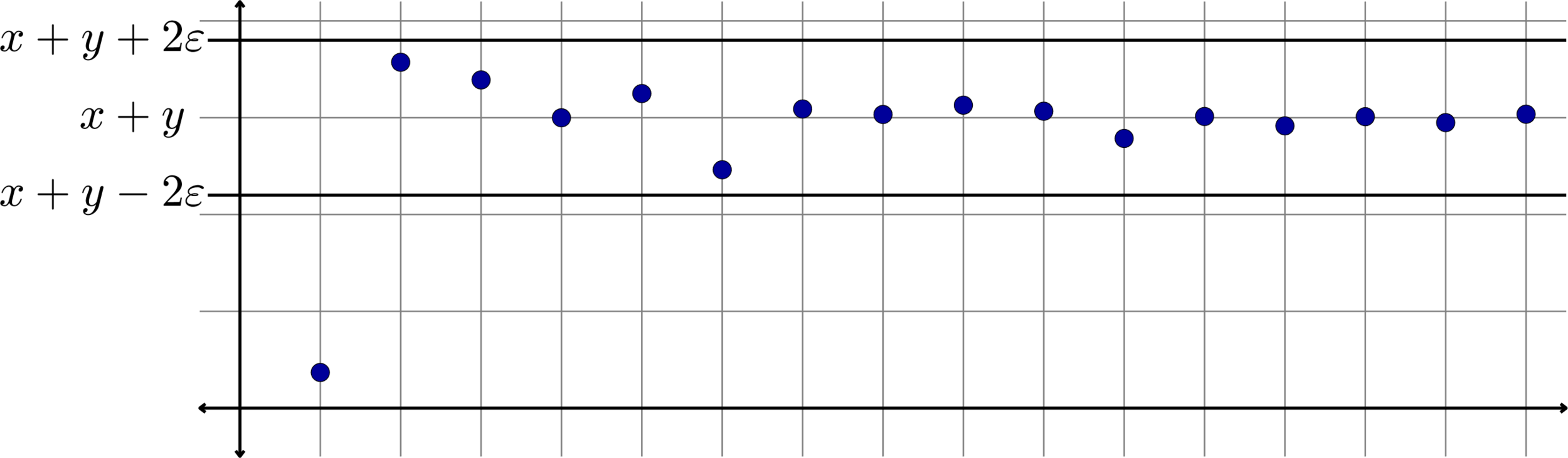

Set \(N=\max\{K,M\}\). If \(n\geq N\), then \(n\geq K\) and \(n\geq M\)

Theorem 1. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X+Y\) has limit \(x+y\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. There exists a number \(K\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\text{ for all }n\geq K.\]

There also exists a number \(M\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}\text{ for all } n\geq M.\]

Set \(N=\max\{K,M\}\). If \(n\geq N\), then \(n\geq K\) and \(n\geq M\) and hence

\[|(x_{n}+y_{n}) - (x+y)| = |(x_{n}-x) - (y_{n}-y)|\leq |x_{n}-x| + |y_{n}-y|\]

\[<\frac{\varepsilon}{2} + \frac{\varepsilon}{2}=\varepsilon.\]

\(\Box\)

Theorem 1. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X+Y\) has limit \(x+y\).

Theorem 2. If \((x_{n})\) converges, then there exists a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\).

Proof. Suppose \((x_{n})\) converges. Let \(x = \lim(x_{n})\). There is a number \(K\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n}-x|<1\text{ for all }n\geq K.\]

Consider the finite set of numbers

\[A=\{|x_{1}|,|x_{2}|,\ldots,|x_{K-1}|\}.\]

Since \(A\) is a finite set, it has a largest element. Let's add one more element to the set, namely \(|x|+1\) and set

\[M = \max\{|x_{1}|,|x_{2}|,\ldots,|x_{K-1}|,|x|+1\}.\]

Note that

\[M\geq |x_{n}| \text{ for }n=1,2,\ldots,K-1.\]

If \(n\geq K\) then we have

\[|x_{n}| = |x_{n} - x+x|\leq |x_{n} - x| + |x|<1+|x|\leq M\]

Thus, for any \(n\in\N\) we have \(|x_{n}|\leq M\). \(\Box\)

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Scratch work. We wish to find \(K(\varepsilon)\in\N\) so that for each \(n\geq K(\varepsilon)\) we have

\[|x_{n}y_{n}-xy|<\varepsilon\]

So, we look more closely:

\[|x_{n}y_{n} - xy| = |x_{n}y_{n} - x_{n}y+x_{n}y - xy| = |x_{n}(y_{n}-y) + (x_{n}-x)y|\]

Close to zero for large \(n\)

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Scratch work. We wish to find \(K(\varepsilon)\in\N\) so that for each \(n\geq K(\varepsilon)\) we have

\[|x_{n}y_{n}-xy|<\varepsilon\]

So, we look more closely:

\[|x_{n}y_{n} - xy| = |x_{n}y_{n} - x_{n}y+x_{n}y - xy| = |x_{n}(y_{n}-y) + (x_{n}-x)y|\]

Close to zero for large \(n\)

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Scratch work. We wish to find \(K(\varepsilon)\in\N\) so that for each \(n\geq K(\varepsilon)\) we have

\[|x_{n}y_{n}-xy|<\varepsilon\]

So, we look more closely:

\[|x_{n}y_{n} - xy| = |x_{n}y_{n} - x_{n}y+x_{n}y - xy| = |x_{n}(y_{n}-y) + (x_{n}-x)y|\]

What if \((x_{n})\) gets big??

It can't!

Theorem 4. If \((x_{n})\) converges, then there exists a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\).

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Scratch work. We wish to find \(K(\varepsilon)\in\N\) so that for each \(n\geq K(\varepsilon)\) we have

\[|x_{n}y_{n}-xy|<\varepsilon\]

So, we look more closely:

\[|x_{n}y_{n} - xy| = |x_{n}y_{n} - x_{n}y+x_{n}y - xy| = |x_{n}(y_{n}-y) + (x_{n}-x)y|\]

\[\leq |x_{n}(y_{n}-y)| + |(x_{n}-x)y| = |x_{n}||y_{n}-y| + |x_{n}-x||y|\]

There is a number \(M>0\) so that \[|x_{n}|\leq M\] for all \(n\in\N.\) We choose \(n\) large enough that BOTH

\[|x_{n}-x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}\quad\text{and}\quad |y_{n}-y|<\frac{\varepsilon}{4M}\]

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given.

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By Theorem 2, there is a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By Theorem 2, there is a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\). There exists \(K_{1}\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|< \frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}\text{ for all }n\geq K_{1}.\]

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By Theorem 2, there is a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\). There exists \(K_{1}\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|< \frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}\text{ for all }n\geq K_{1}.\]

There exists a number \(K_{2}\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|<\frac{\varepsilon}{4M} \text{ for all }n\geq K_{2}.\]

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By Theorem 2, there is a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\). There exists \(K_{1}\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}\text{ for all }n\geq K_{1}.\]

There exists a number \(K_{2}\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|<\frac{\varepsilon}{4M} \text{ for all }n\geq K_{2}.\]

Set \(K = \max\{K_{1},K_{2}\}.\) If \(n\geq K\), then \(n\geq K_{1}\) and \(n\geq K_{2}\)

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By Theorem 2, there is a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\). There exists \(K_{1}\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}\text{ for all }n\geq K_{1}.\]

There exists a number \(K_{2}\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|<\frac{\varepsilon}{4M} \text{ for all }n\geq K_{2}.\]

Set \(K = \max\{K_{1},K_{2}\}.\) If \(n\geq K\), then \(n\geq K_{1}\) and \(n\geq K_{2}\), and

\[|x_{n}y_{n} - xy| = |x_{n}y_{n} - x_{n}y+x_{n}y - xy| = |x_{n}(y_{n}-y) + (x_{n}-x)y|\]

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By Theorem 2, there is a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\). There exists \(K_{1}\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|< \frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}\text{ for all }n\geq K_{1}.\]

There exists a number \(K_{2}\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|< \frac{\varepsilon}{4M} \text{ for all }n\geq K_{2}.\]

Set \(K = \max\{K_{1},K_{2}\}.\) If \(n\geq K\), then \(n\geq K_{1}\) and \(n\geq K_{2}\), and

\[|x_{n}y_{n} - xy| = |x_{n}y_{n} - x_{n}y+x_{n}y - xy| = |x_{n}(y_{n}-y) + (x_{n}-x)y|\]

\[\leq |x_{n}(y_{n}-y)| + |(x_{n}-x)y| = |x_{n}||y_{n}-y| + |x_{n}-x||y|\]

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By Theorem 2, there is a number \(M>0\) such that \(|x_{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\). There exists \(K_{1}\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|< \frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}\text{ for all }n\geq K_{1}.\]

There exists a number \(K_{2}\in\N\) such that

\[|y_{n} - y|< \frac{\varepsilon}{4M} \text{ for all }n\geq K_{2}.\]

Set \(K = \max\{K_{1},K_{2}\}.\) If \(n\geq K\), then \(n\geq K_{1}\) and \(n\geq K_{2}\), and

\[|x_{n}y_{n} - xy| = |x_{n}y_{n} - x_{n}y+x_{n}y - xy| = |x_{n}(y_{n}-y) + (x_{n}-x)y|\]

\[\leq |x_{n}(y_{n}-y)| + |(x_{n}-x)y| = |x_{n}||y_{n}-y| + |x_{n}-x||y|\]

\[\leq M\frac{\varepsilon}{4M} + \frac{\varepsilon}{4(|y|+1)}|y| = \varepsilon\left(\frac{1}{4} + \frac{|y|}{4(|y|+1)}\right) \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2}<\varepsilon\]

\(\Box\)

Theorem 3. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) and \(Y=(y_{n})\) be sequences of real numbers with limits \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then, the sequence \(X\cdot Y\) has limit \(xy\).

Theorem 3. If \(X=(x_{n})\) is a real sequence with limit \(x\), and \(c\in\R\), then the sequence \(cX\) has limit \(cx\).

Proof. Note that if \(c=0\), then \(cX\) is the constant sequence with each term equal to zero. We have already seen that \(\lim(0)=0\). Thus, we may assume \(c\neq 0\).

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Since \(\frac{\varepsilon}{|c|}>0\) we know that there exists \(K\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{|c|}\text{ for all }n\geq K.\]

Hence, for any \(n\geq K\) we have

\[|c||x_{n} - x|<\varepsilon.\]

To complete the proof, we let \(n\geq K\) be arbitrary, and we notice that

\[|cx_{n} - cx| = |c(x-x_{n})| = |c||x_{n} - x|<\varepsilon.\]

\(\Box\)

Practice Problem. Prove the following theorem:

End Lecture 21

Read Section 3.2 again

Lecture 21

By John Jasper

Lecture 21

- 272