Lecture 24:

Subsequences

Definition. Let \(X = (x_{n})\) be a sequence of real numbers, and let \(n_{1}<n_{2}<n_{3}<\cdots<n_{k}<\cdots\) be a strictly increasing sequence of natural numbers. Then, the sequence

\[X' = (x_{n_{1}},x_{n_{2}},x_{n_{3}},\ldots,x_{n_{k}},\ldots)\]

is called a subsequence of \(X\).

Examples. Let \(X = (\frac{1}{n})\). Each of the following is a subsequence of \(X\):

\[\left(\frac{1}{3n}\right) = \left(\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{6},\frac{1}{9},\frac{1}{12},\ldots\right)\]

\[\left(\frac{1}{n^2}\right) = \left(\frac{1}{1},\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{9},\frac{1}{16},\ldots\right)\]

\[\left(\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{5},\frac{1}{7},\frac{1}{11},\frac{1}{13},\frac{1}{17},\ldots\right)\]

But

\[\left(\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{5},\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{7},\frac{1}{6},\ldots\right)\quad\text{and}\quad \left(\frac{2}{3},\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{5},\frac{1}{6},\ldots\right)\]

are not subsequences

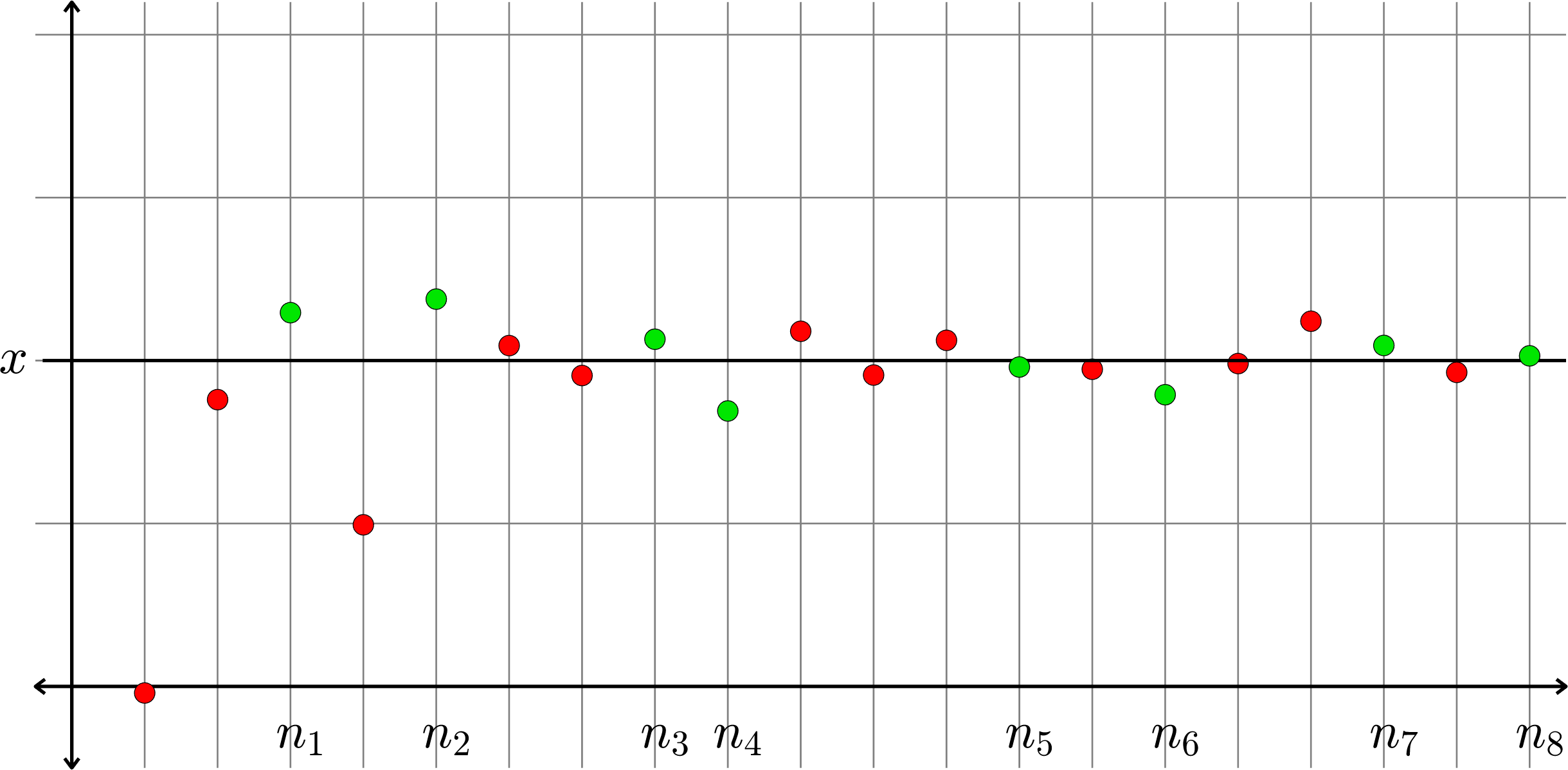

Consider a sequence \(X = (x_{n})\), graphed below in red, with limit \(x.\)

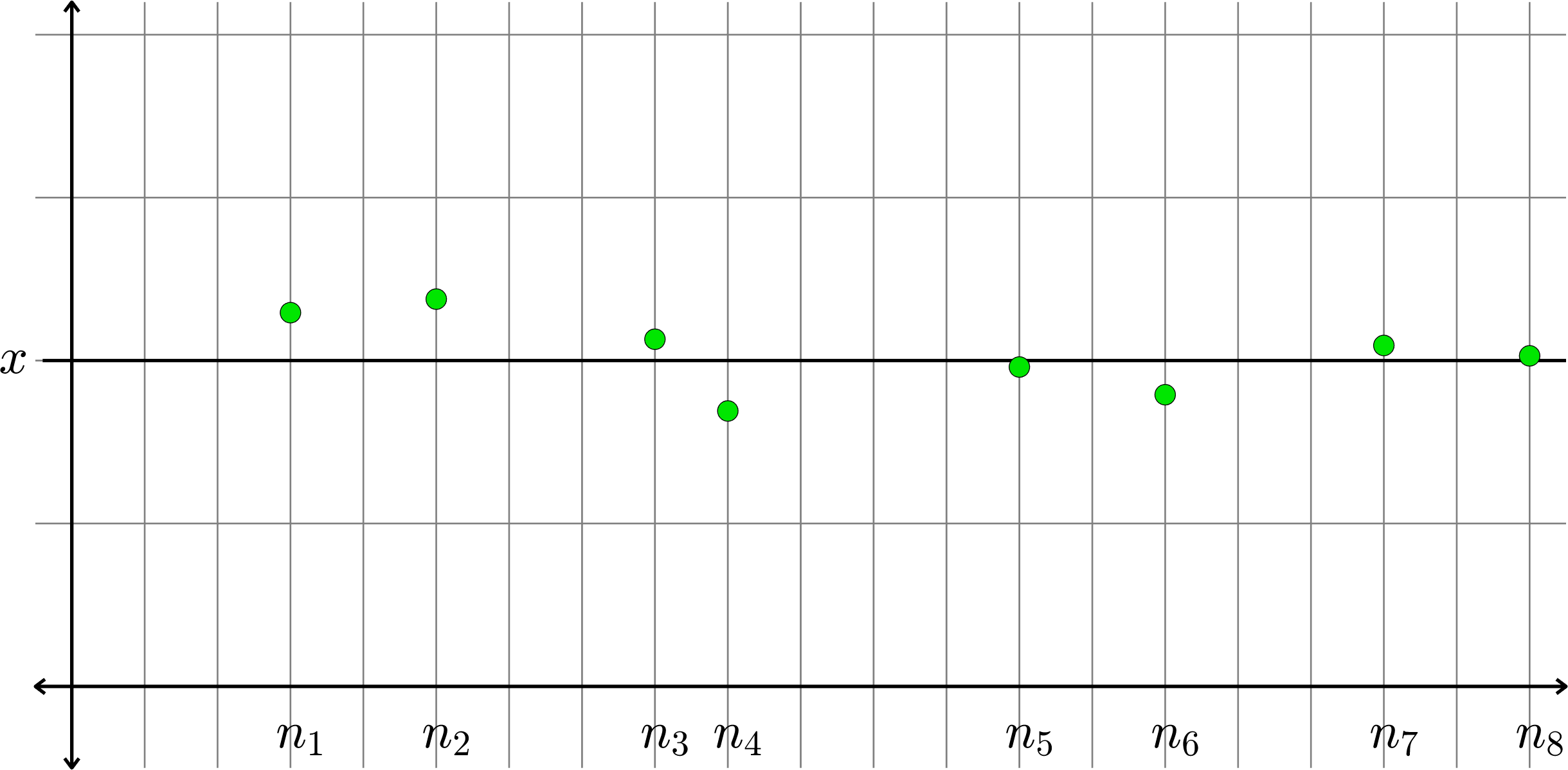

The sequence \(X'=(x_{n_{k}}) = (x_{n_{1}},x_{n_{2}},\ldots)\) graphed below in green, is a subsequence of \(X\).

But \(X'\) is a sequence in it's own right! And it looks like \(\lim X'=x\) too!

Theorem 3.4.2 If a sequence \(X = (x_{n})\) of real number converges to a real numbers \(x\), then any subsequence \(X'=(x_{n_{k}})\) also converges to \(x.\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. There exists \(K\in\N\) such that

\[|x_{n} - x|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq K.\]

Since \(n_{1}<n_{2}<\cdots<n_{k}<\cdots,\) we can easily prove (by induction) that \(n_{K}\geq K\). Therefore, if \(k\geq K\), then \(n_{k}\geq n_{K}\geq K\), and hence

\[|x_{n_{k}} - x|<\varepsilon.\]

Thus, for any \(\varepsilon>0\) we have found a natural number \(K\) such that

\[|x_{n_{k}}-x|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }k\geq K.\]

Therefore, the subsequence \((x_{n_{k}})\) converges to \(x\). \(\Box\)

Proposition. If \(0<b<1\), then \(\lim(b^{n})=0\).

Proof. Since \(b<1\) and \(b>0\) we see (by induction) that \(b^{n+1}<b^{n}\) for every \(n\in\N\). This shows that \((b^{n})\) is a decreasing sequence. Since \(b^n>0\) for all \(n\in\N\), the sequence is bounded below. By the monotone convergence theorem \((b^{n})\) has a limit, call it \(x\).

Set \(X = (b^{n})\). By Theorem 3.2.3 (a), the sequence \(X\cdot X = ((b^{n})^2) = (b^{2n})\) converges to \(x^2\). However, \(X\cdot X\) is a subsequence of \(X\). From Theorem 3.4.2 we see that \(x=x^2\). This means that either \(x=0\) or \(x=1\). Since \(b^{n}<1\) for all \(n\in\N\), and \((b^{n})\) is decreasing, we deduce that \(x=0\). \(\Box\)

Theorem (Divergence Criteria (i)). Assume \(X=(x_{n})\) is a sequence of real numbers. If there exist two convergent subsequences \(X'=(x_{n_{k}})\) and \(X'' = (x_{m_{k}})\) such that

\[\lim X' \neq \lim X''\]

then \(X\) is divergent.

Proof. If \(X\) is convergent, then any two subsequences must have the same limit by Theorem 3.4.2. \(\Box\)

Contrapositive: Assume \(X=(x_{n})\) is a sequence of real numbers. If \(X\) is convergent, then any two convergent subsequences \(X'\) and \(X''\) have the same limit.

Theorem (Divergence Criteria (ii)). Assume \(X=(x_{n})\) is a sequence of real numbers. If \(X\) is unbounded, then \(X\) is divergent.

Proof. We proved that convergent sequences are bounded. This is the contrapositive of that statement. \(\Box\)

Practice problem. Use the Divergence Criteria to show that \(\big((-1)^{n}\big)\) is divergent.

Consider the subsequences \(X' = \big((-1)^{2n}\big)\) and \(X'' = \big((-1)^{2n-1}\big)\). Notice that

\[X' = (1,1,1,\ldots)\]

and

\[X'' = (-1,-1,-1,\ldots)\]

Hence \(\lim X' = 1\neq -1 = \lim X''\). By the Divergence Criteria \(\big((-1)^{n}\big)\) is divergent.

Lecture 24

By John Jasper

Lecture 24

- 287