Lecture 6:

Distance and the real line

The real line

A useful way to visualize the set of real numbers is to consider a line, extending infinitely far in both directions, then associate each point on the line with a real number.

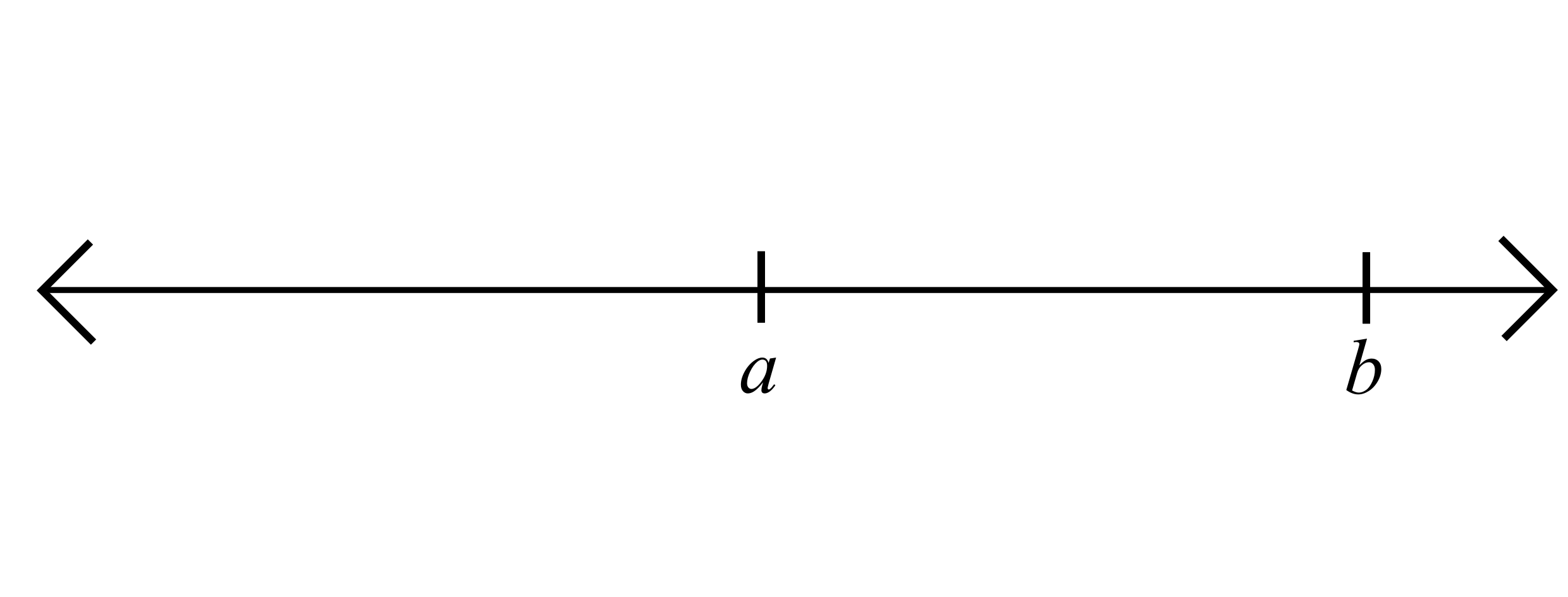

This is possible, since we now have a notion of the order of the real numbers, that is, given two real numbers \(a\) and \(b\), if \(a<b\), then we put \(a\) to the left of \(b\) on the number line.

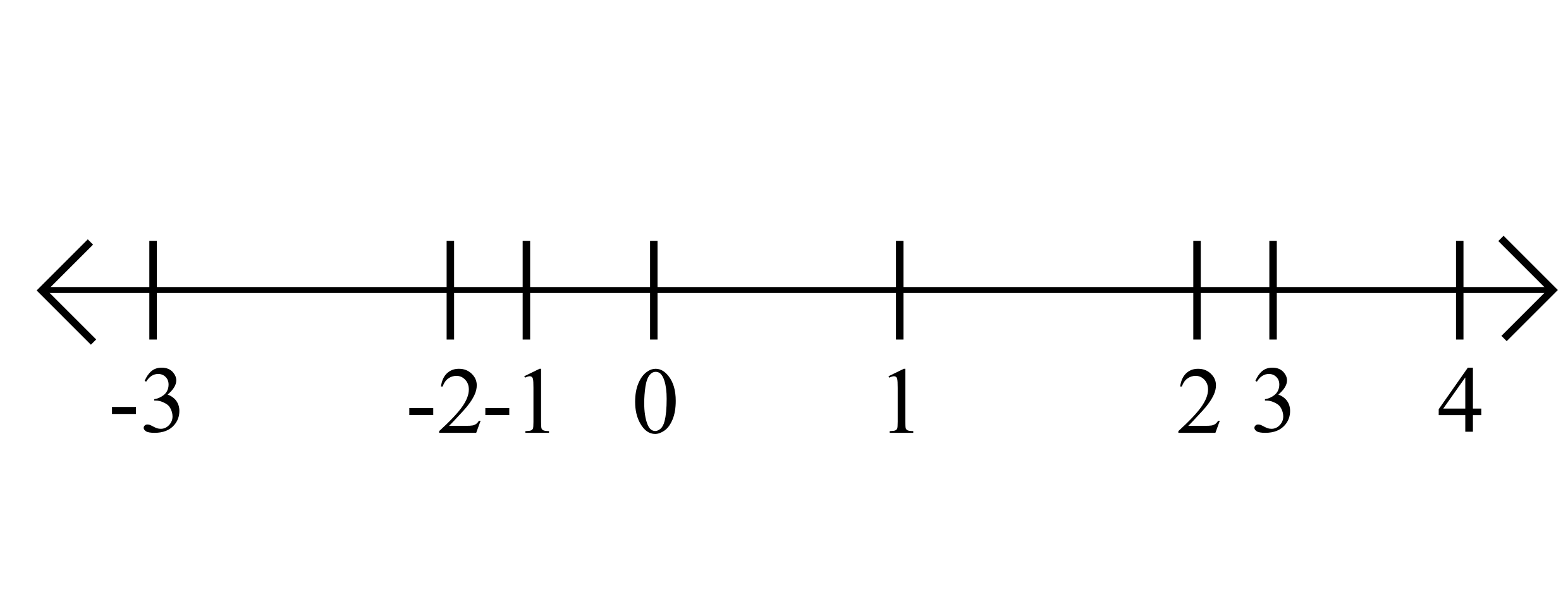

However, with just an order, we would have no notion of how far apart the numbers should be. We'd have no reason not to label our number line as follows:

The real line

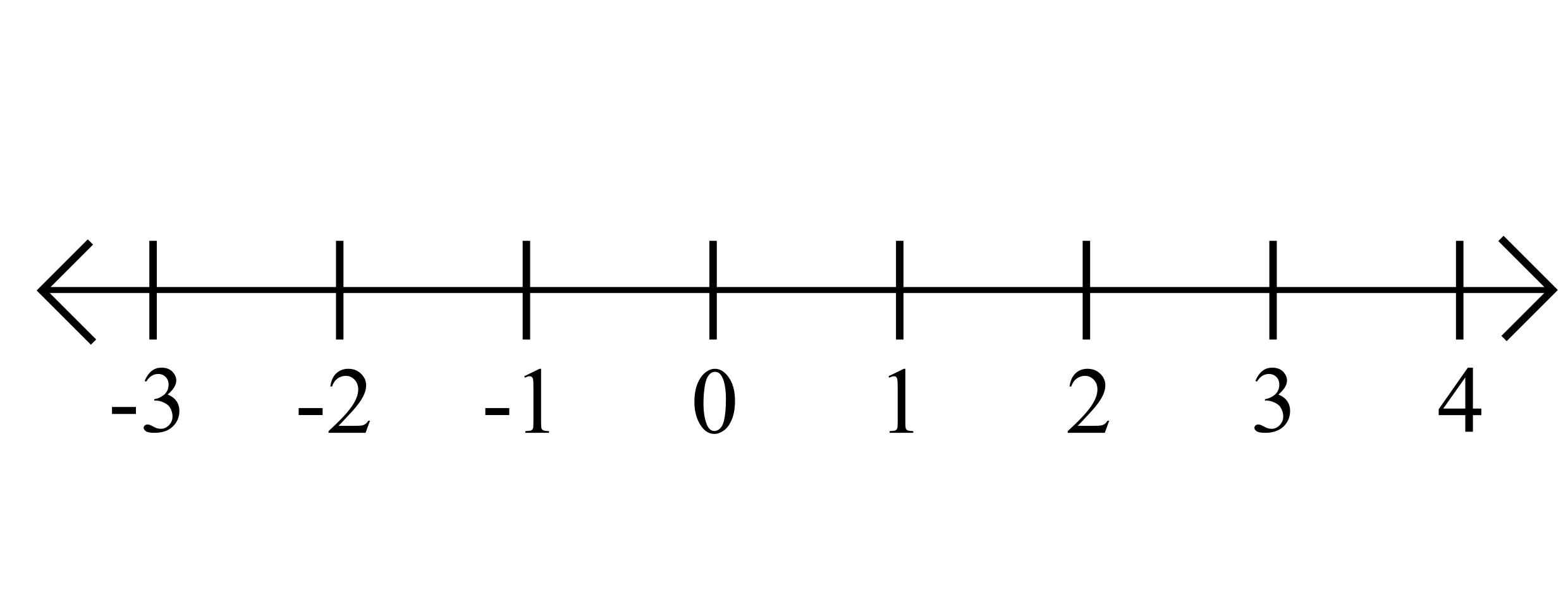

Why do we usually draw the number line like this?

Because absolute value gives us a notion of distance between numbers.

Definition. Given \(a,b\in\mathbb{R}\), the distance between \(a\) and \(b\) is defined to be the number \(|a-b|\). (Note that this is equal to \(|b-a|\).)

Example. \(|1-2|=1,\ |2-3|=1,\ |3-4|=1,\ldots\)

Which is why the integers are equally spaced on the number line!

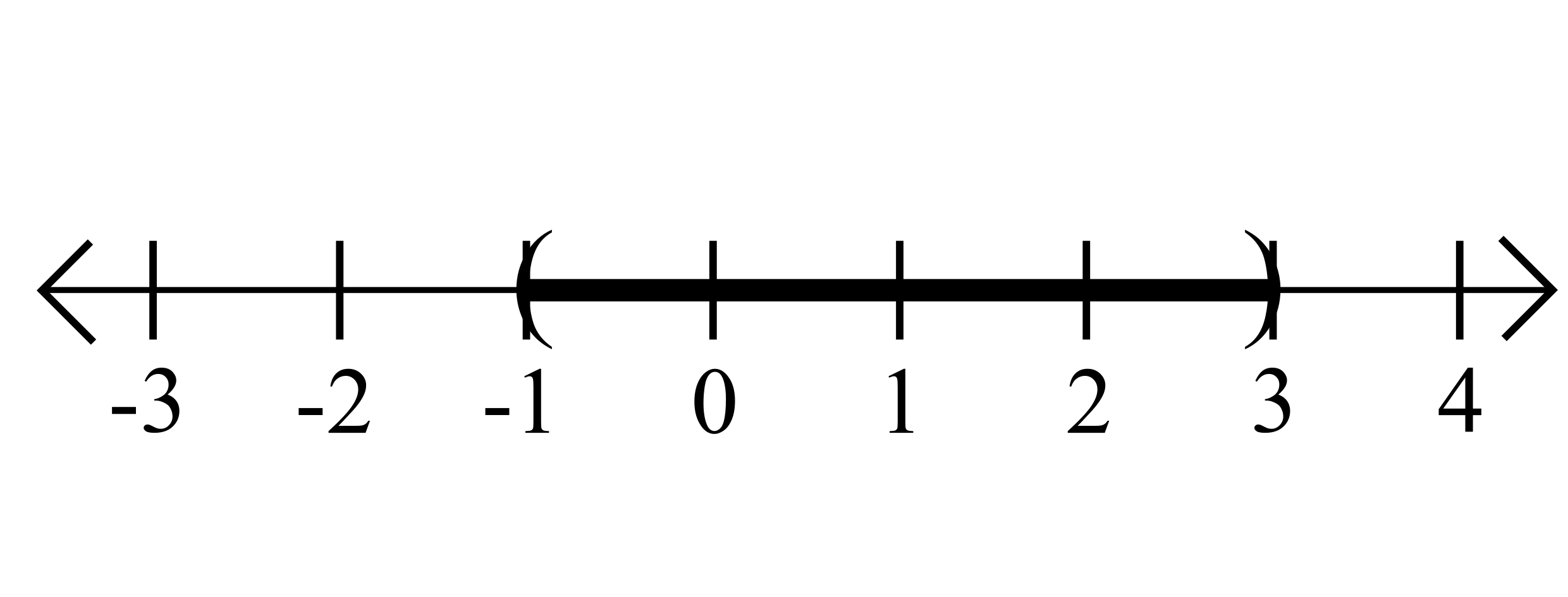

This gives us a way to visualize sets such as

\[A = \{x\in \mathbb{R} : |x-1|<2\}\]

This is the set of all real numbers \(x\) such that the distance between \(x\) and \(1\) is strictly less than \(2\).

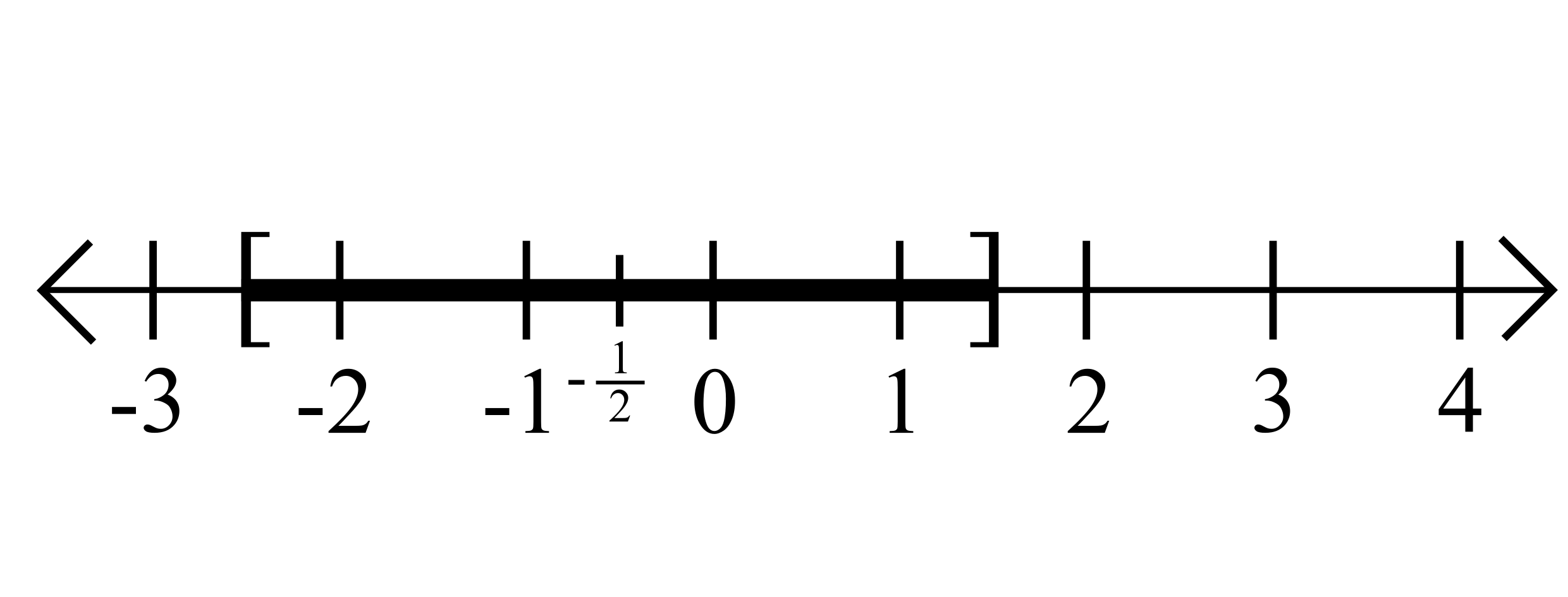

Consider the set

\[B = \{x\in \mathbb{R} : |2x+1|\leq 4\}\]

We can rewrite

\[|2x+1|\leq 4\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad 2\left|x-\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)\right|\leq 4 \quad\Leftrightarrow\quad \left|x-\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)\right|\leq 2\]

Hence, \(B\) is the set of all numbers \(x\) such that the distance between \(x\) and \(-\frac{1}{2}\) is less than or equal to \(2\).

\[=(-1,3)\]

\[=[-\tfrac{5}{2},\tfrac{3}{2}]\]

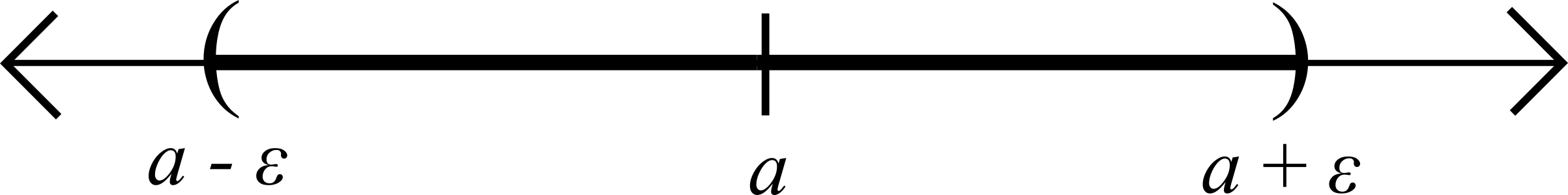

Definition. Let \(a\in\R\) and \(\varepsilon>0\). Then the \(\varepsilon\)-neighborhood of \(a\) is the set

\[V_{\varepsilon}(a) = \{x\in\R : |x-a|<\varepsilon\}.\]

In interval notation \(V_{\varepsilon}(a) = (a-\varepsilon,a+\varepsilon)\).

Proof. Suppose \(x\in V_{\delta}(a)\). By definition \(|x-a|<\delta\). Since \(\delta\leq \varepsilon\), we see that \(|x-a|<\varepsilon\), that is, \(x\in V_{\varepsilon}(a)\). Since we have shown that for an arbitrary element \(x\in V_{\delta}(a)\), it follows that \(x\in V_{\varepsilon}(a)\), this shows that \(V_{\delta}(a)\subset V_{\varepsilon}(a)\), as desired. \(\Box\)

Proposition . If \(\varepsilon\geq \delta>0\), then \(V_{\delta}(a)\subset V_{\varepsilon}(a)\).

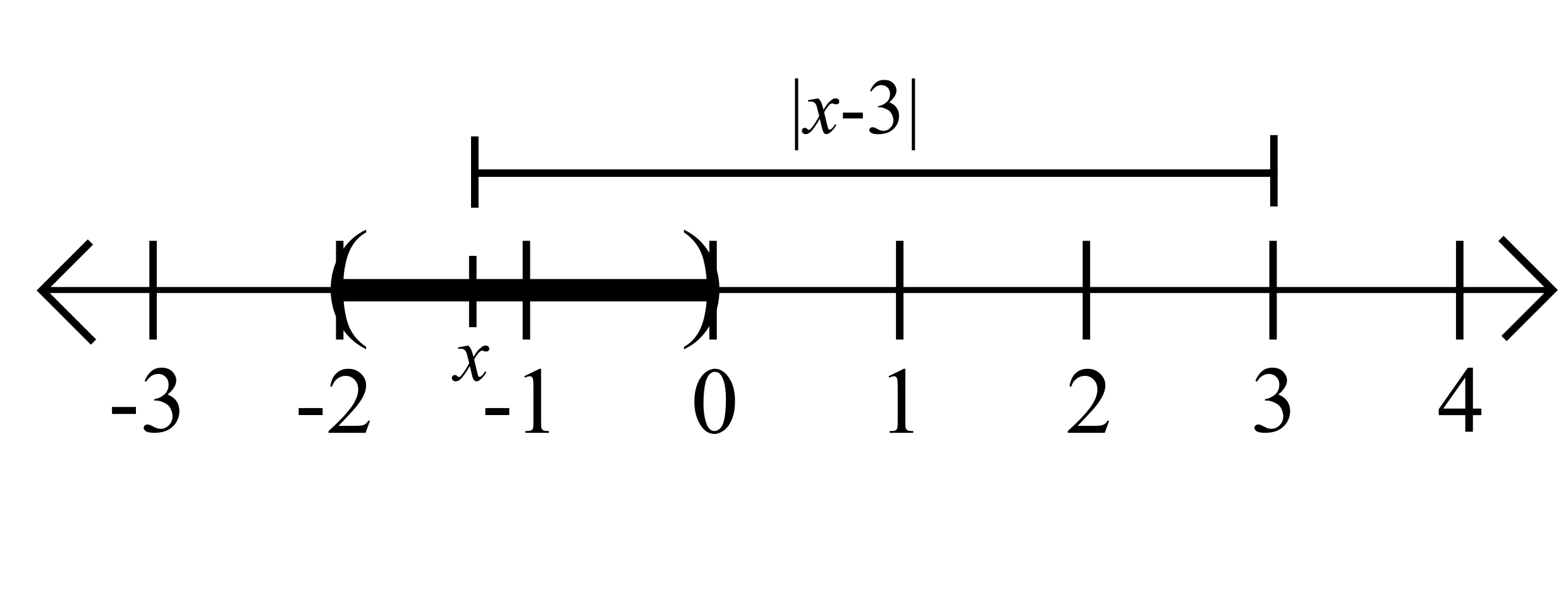

Practice problem:

Write out the following set in interval notation.

\[D=\{|x-3| : x\in V_{1}(-1)\}\]

The set \(D\) is the set of all distances between numbers in \(V_{1}(-1) = (-2,0)\) and the number \(3\).

Hence, it appears that \(D = (3,5)\). Let's prove it! (Go to next slide)

End Lecture 6

Read Section 2.2 again

Proposition. \(\{|x-3| : x\in V_{1}(-1)\} = (3,5).\)

Proof. First, we will show that \(\{|x-3| : x\in V_{1}(2)\} \subset (3,5)\).

Let \(y\in\{|x-3|:x\in V_{1}(-1)\}\). Therefore, \(y=|x-3|\) for some number in \(x\in V_{1}(-1)=(-2,0)\). Note that \(-2<x<0\) and thus \(-5<x-3<-3\). In particular, \(x-3\) is negative, and thus

\[y=|x-3|=-(x-3)=3-x.\]

From the fact that \(-2<x<0\) we can deduce that \(3<3-x<5\), and thus \(y=3-x\in (3,5)\).

Next, we will show that \((3,5)\subset \{|x-3| : x\in V_{1}(2)\} \). Let \(y\in (3,5)\), that is, \(3<y<5\). Set \(x=3-y\). Our assumptions about \(y\) imply that \(-2<x<0\), that is, \(x\in V_{1}(-1)\). Finally, we see that

\[|x-3| = |(3-y)-3|=|-y| = y.\]

This shows that \(y\in \{|x-3| : x\in V_{1}(-1)\}\) and this completes the proof. \(\Box\)

Lecture 6

By John Jasper

Lecture 6

- 209