Lecture 29:

Functions

Functions

Definition. Given two sets \(X\) and \(Y\), a function is a subset \(f\) of the cartesian product \(X\times Y\) with the property that if \((a,b)\in f\), \((c,d)\in f\), and \(a=c\), then \(b=d\). The set \(X\) is called the domain of \(f\), the set \(Y\) is called the codomain of \(f\). The set \(\{y : \exists\, x\in X,\ (x,y)\in f\}\) is called the range of \(f\).

Notation:

To write the statement "\(f\) is a function with domain \(X\) and codomain \(Y\)" we write

\[f:X\to Y.\]

Given \(f:X\to Y\), instead of writing \((a,b)\in f\) we usually write

\[f(a)=b.\]

The most common way to define a function is to say something like

"Let \(f:X\to Y\) be given by

\[f(x) = (\text{formula involving }x)"\]

Example 1. Let \(f:(0,1)\to\R\) be given by \(f(x) = 2x^2-1\). The domain of \(f\) is \((0,1)\). Note that \(f(0)\) is not defined, nor is \(f(1)\).

Example 2. Consider the function \(g\) given by

\[g(x) = \frac{2x}{x(x-3)}.\]

When the domain is not specified, it is the set of real numbers \(x\) such that \(g(x)\) is defined. So, the domain of \(g\) is \((-\infty,0)\cup(0,3)\cup(3,\infty)\).

Example 3. Let \(h:\R\to\R\) be given by

\[h(z) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } z>1,\\ \dfrac{z}{z-2} & \text{if }z\leq 1.\end{cases}\]

Note that \(h(1)=\dfrac{1}{1-2}=-1\).

Defining Functions

Example 4. Let \(S:\R\to\R\) be given by

\[S(x) = |\{a\in\R : a^2+xa+1=0\} |\]

Where for a set \(X\), the symbol \(|X|\) is the number of elements in the set \(X\). For example,

\[S(2) = |\{a\in\R : a^2+2a+1=0\}|\]

Since

\[\{a\in\R : a^2+2a+1=0\} = \{-1\}\]

we see that \(S(2) = 1\). Can you find \(S(-1)\)?

Function Notation

Let \(f:\R\to \R\) be given by

\[f(x) = x^2+2x-5.\]

We can plug any number into the function \(f\):

\[f(x) = x^2+2x-5\]

\[f(z) = z^2+2z-5\]

\[f(\varepsilon) = \varepsilon^2+2\varepsilon-5\]

\[f(x+h) = (x+h)^2+2(x+h)-5\]

Remember, \(f(w)\) and \(w^2+2w-5\) are THE SAME THING. Hence, we can write things like

\[r^2+r = f(r) -r+5,\]

\[f(x+h) - f(x) = 2xh+h^2+2h,\]

and

\[ 1= f(-3)+3.\]

Graphs of functions

Definition. Given a function \(f:X\to Y\) the graph of the function \(f\) is the set \(\{(x,f(x)) : x\in X\}\).

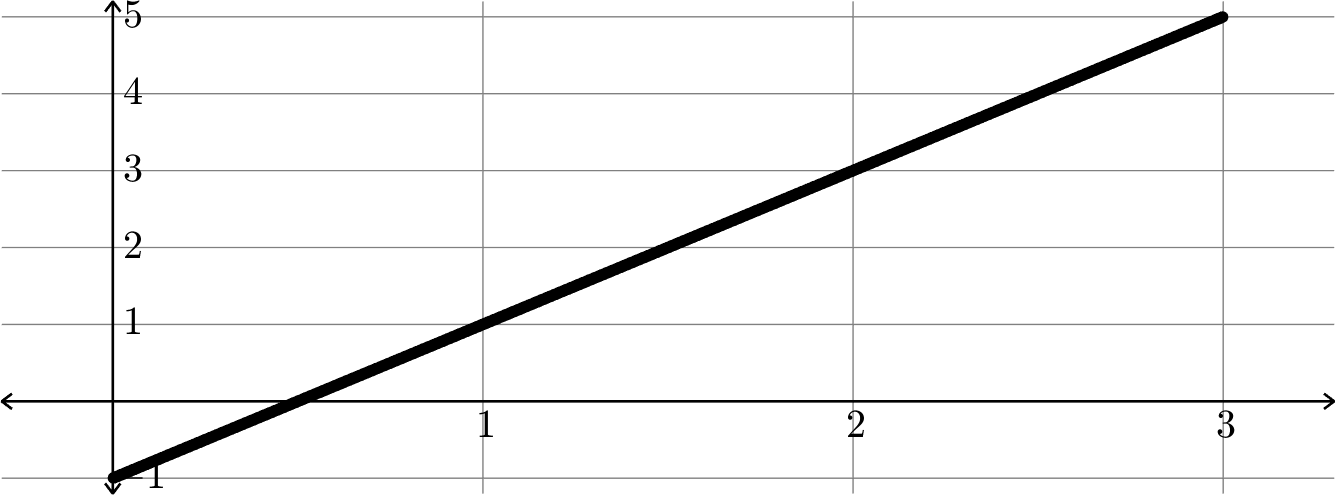

Example. If \(f:\R\to\R\) is given by \(f(x) = 2x-1\), then the graph of \(f\) is the set

\[\{(x,2x-1) : x\in\R\}.\]

If we start plotting the points in the plane, then we can get a picture of the graph of \(f\).

Graphs of functions

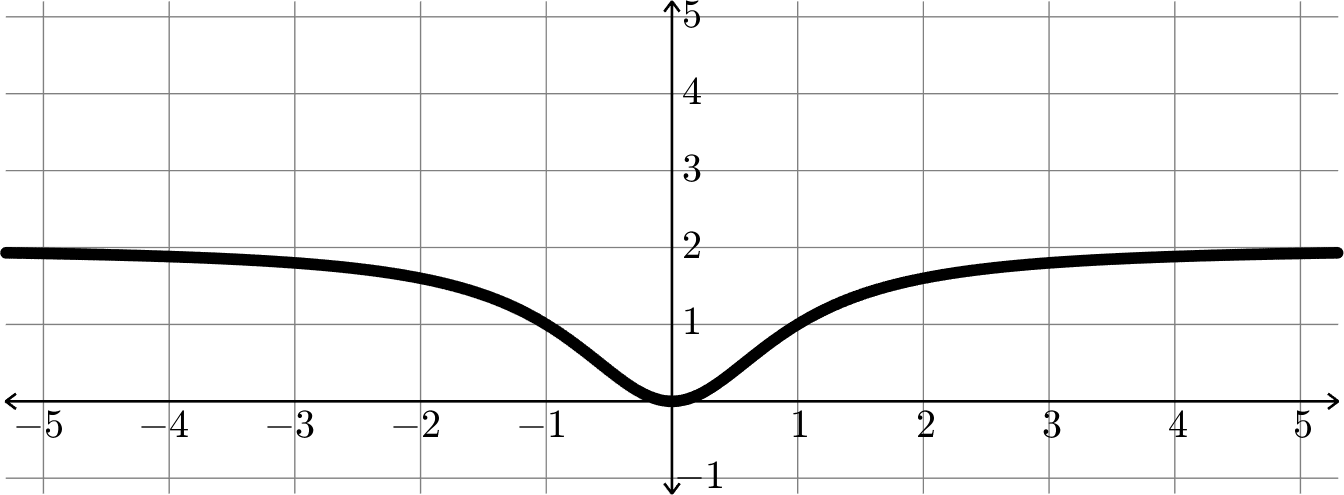

Example. If \(g:\R\to\R\) is given by \(g(x) = \dfrac{2x^2}{x^2+1}\), then the graph of \(g\) is the set

\[\left\{\left(x,\dfrac{2x^2}{x^2+1}\right) : x\in\R\right\}.\]

If we start plotting the points in the plane, then we can get a picture of the graph of \(g\).

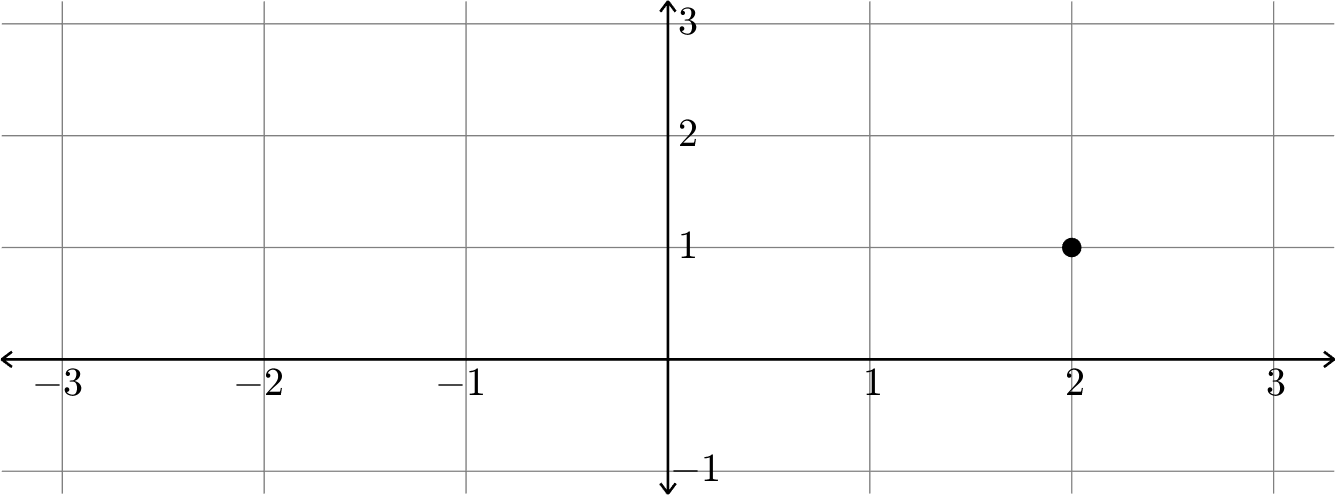

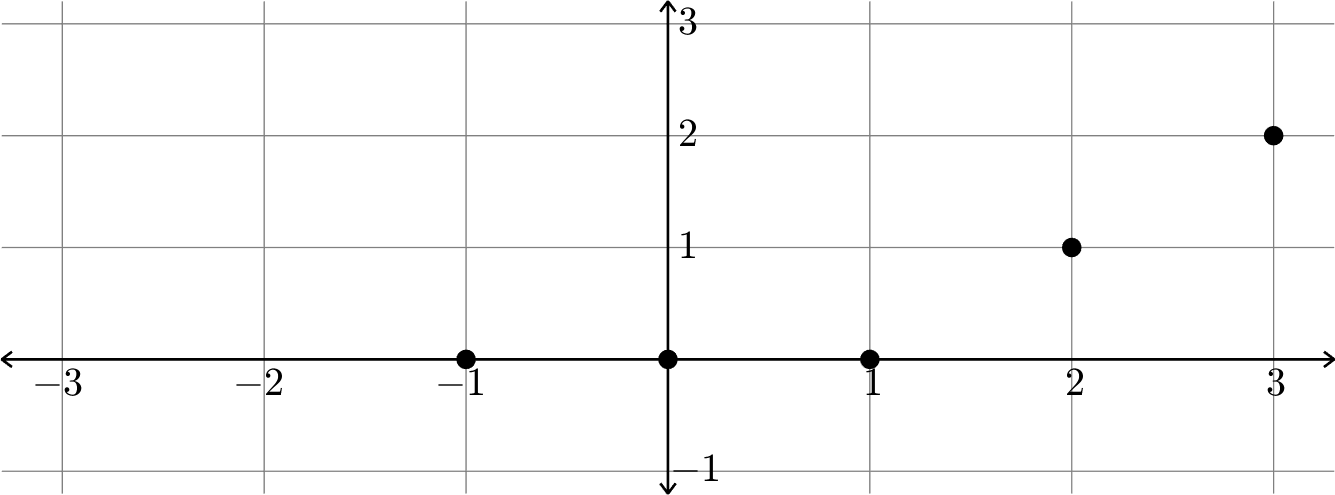

Practice Problem. Let \(S:\R\to\R\) be the function from Example 4. Draw the graph of \(S\). Start by plotting at least 5 points of the graph.

\[S(2) = |\{a\in\R : a^2+2a+1=0\}|\]

Since

\[\{a\in\R : a^2+2a+1=0\} = \{-1\}\]

we see that \(S(2) = 1\). Thus, \((2,1)\) is a point of the graph of \(S\).

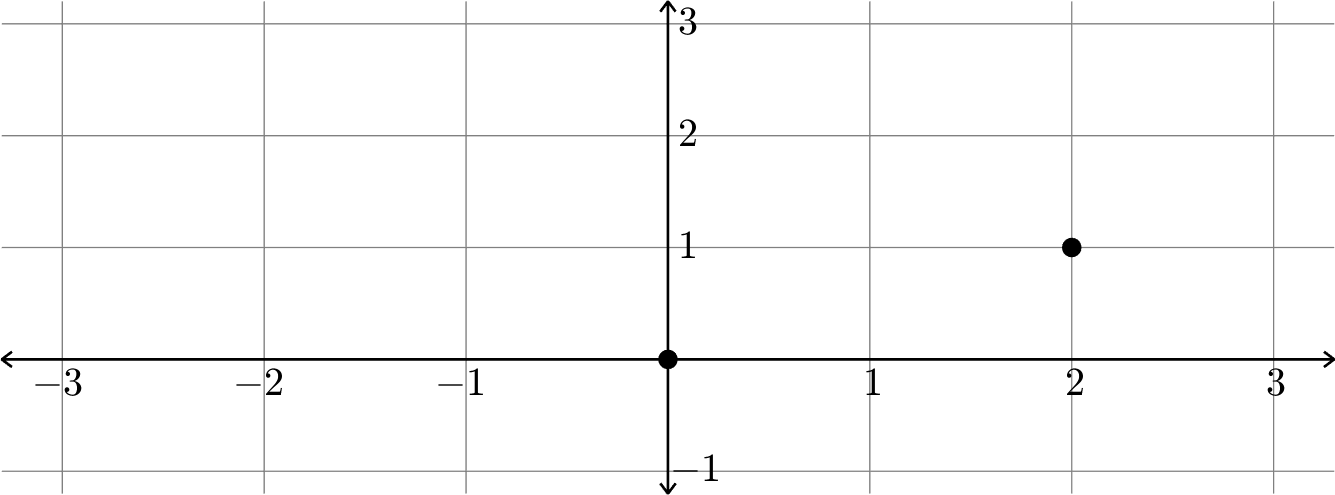

Practice Problem. Let \(S:\R\to\R\) be the function from Example 4. Draw the graph of \(S\). Start by plotting at least five points of the graph.

\[S(0) = |\{a\in\R : a^2+1=0\}|\]

Since

\[\{a\in\R : a^2+1=0\} = \varnothing\]

we see that \(S(0) = 0\). Thus, \((0,0)\) is a point of the graph of \(S\).

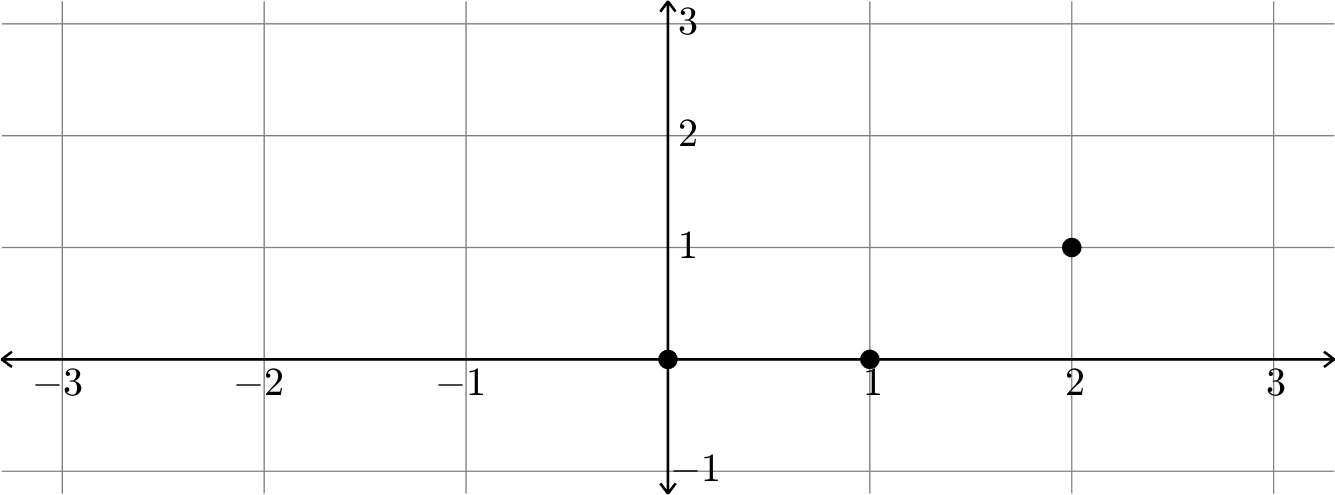

Practice Problem. Let \(S:\R\to\R\) be the function from Example 4. Draw the graph of \(S\). Start by plotting at least five points of the graph.

\[S(1) = |\{a\in\R : a^2+a+1=0\}|\]

Since

\[\{a\in\R : a^2+a+1=0\} = \varnothing\]

we see that \(S(1) = 0\). Thus, \((1,0)\) is a point of the graph of \(S\).

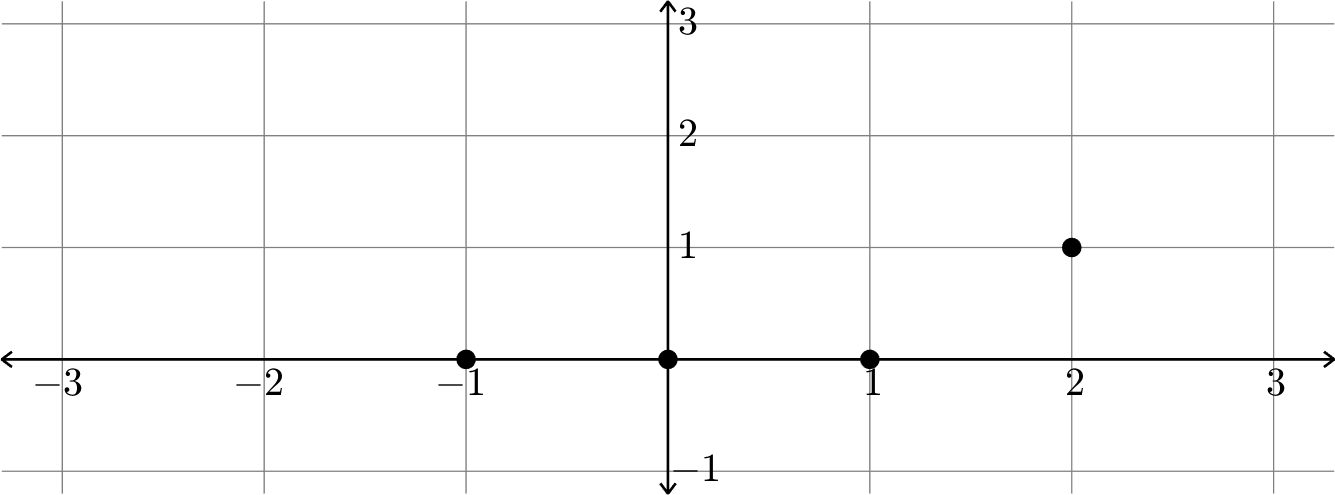

Practice Problem. Let \(S:\R\to\R\) be the function from Example 4. Draw the graph of \(S\). Start by plotting at least five points of the graph.

\[S(-1) = |\{a\in\R : a^2-a+1=0\}|\]

Since

\[\{a\in\R : a^2-a+1=0\} = \varnothing\]

we see that \(S(-1) = 0\). Thus, \((-1,0)\) is a point of the graph of \(S\).

Practice Problem. Let \(S:\R\to\R\) be the function from Example 4. Draw the graph of \(S\). Start by plotting at least five points of the graph.

\[S(3) = |\{a\in\R : a^2+3a+1=0\}|\]

Since \[\{a\in\R : a^2+3a+1=0\} = \left\{\frac{-3+\sqrt{5}}{2},\frac{-3-\sqrt{5}}{2}\right\}\]

we see that \(S(3) = 2\). Thus, \((3,2)\) is a point of the graph of \(S\).

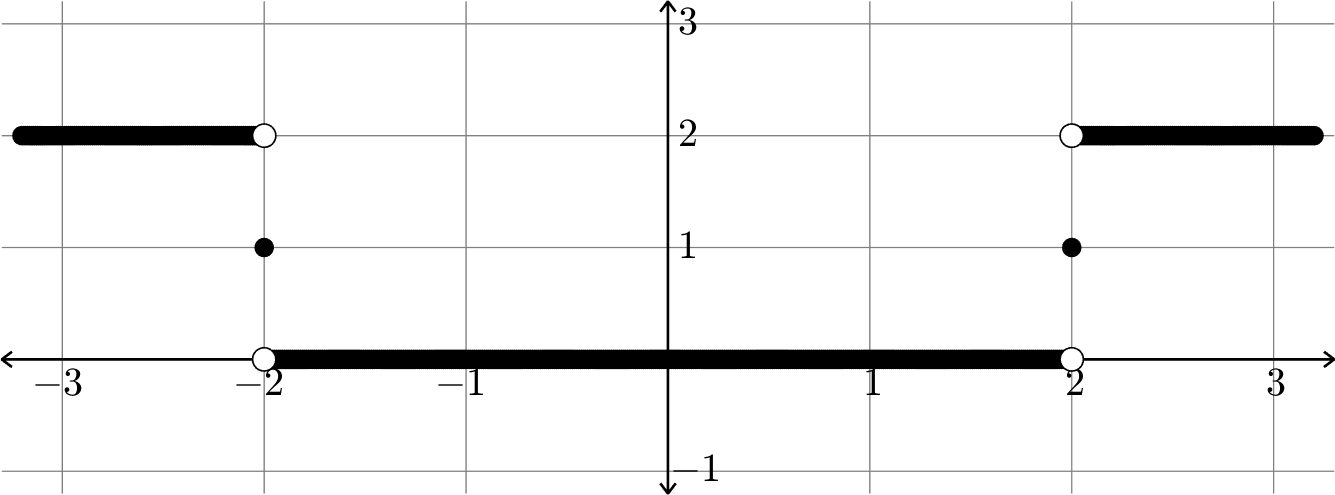

Practice Problem. Let \(S:\R\to\R\) be the function from Example 4. Draw the graph of \(S\). Start by plotting at least five points of the graph.

Note that \(S(x)\) is the number of solutions to the equation \(a^2+xa+1=0\) (where \(a\) is the variable we are solving for). This is a quadratic equation, so the number of solutions is determined by the discriminant

\[x^2-4\]

If the discriminant is negative, then the equation has no solutions. If the discriminant is zero, then the equation has exactly one solution. If the discriminant is positive, then the equation has two solutions, hence

Definition 4.1.4. Let \(A\subseteq\R\), and let \(c\) be a cluster point of \(A\). For a function \(f: A\to\R\), a real number \(L\) is said to be the limit of \(f\) at \(c\) if, given any \(\varepsilon>0\), there exists \(\delta>0\) such that if \(x\in A\) and \(0<|x-c|<\delta\), then \(|f(x)-L|<\varepsilon.\)

Example. Consider the function \(f:(0,1]\to\R\) given by \(f(x) = x.\)

Steps in a proof.

1) Take an arbitrary \(\varepsilon>0\): Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given.

2) Choose a \(\delta>0\) that works: Set \(\delta = \varepsilon\).

4) Show that \(|f(x)-L|<\varepsilon\). By our choice of \(\delta\) we have \(|x|<\varepsilon,\) and hence \[|f(x) - 0| = |x|<\varepsilon.\]

3) Take an arbitrary \(x\) in the domain such that \(0<|x-c|<\delta\):

Let \(x\in (0,1]\) such that \(0<|x-0|<\delta\) be given.

Claim. \(0\) is the limit of \(f\) at \(0.\)

Claim. \(\displaystyle{\lim_{x\to 0} \frac{2x}{x(x-3)}=-\frac{2}{3}}.\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \[\delta=\min\left\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2},1\right\}.\] Let \(x\in (-\infty,0)\cup(0,3)\cup(3,\infty)\) such that \(0<|x-0|<\delta\). By our choice of \(\delta\) we have \(|x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\) We also see that \(|x|<1\) and hence \(|x-3|>2.\) Using this we have

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}<\frac{1}{2}.\]

Finally, we compute

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right| = \left|\frac{2}{x-3} +\frac{2}{3}\right| = \left|\frac{6}{3(x-3)} +\frac{2(x-3)}{3(x-3)}\right|= \left|\frac{2x}{3(x-3)}\right|\]

\[ = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\leq \frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon}{2} = \frac{\varepsilon}{6}<\varepsilon.\]

How did we figure that out?

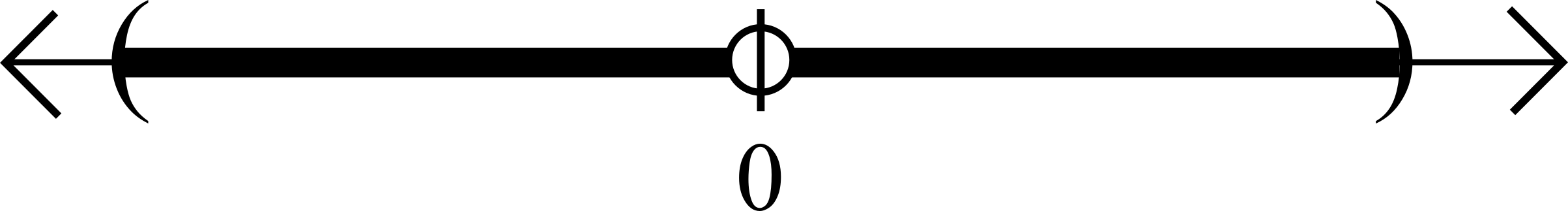

We know that for each \(\varepsilon>0\) we have to find a \(\delta>0\) such that every \(x\) in

\[-\delta\]

\[\delta\]

That is, every \(x\) that satisfies \(0<|x-0|<\delta\) we must have

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right|<\varepsilon\]

Thus, we look closely at the expression on the left above:

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right|= \left|\frac{2x}{3(x-3)}\right| = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\]

What can we say about \(\dfrac{1}{|x-3|}\) and \(|x|\) when \(\delta\) is small?

If \(\delta\) is very small, then \(x\approx 0\) and hence

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}\approx\frac{1}{3}\quad\text{ and }\quad|x|\approx 0.\]

Let's actually be precise: If \(\delta<1\) then \(|x|<\delta\) implies that \(-1<x<1.\)

This implies \(-4<x-3<-2\), and hence \(|x-3|>2\). Rearranging this inequality we have

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}<\frac{1}{2}.\]

Thus, if we choose our \(\delta\) to be less than \(1\) then we will have

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right|= = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\leq \frac{1}{3}|x|\]

From here, we see that it is enough to choose \(\delta\) to be less than \(\varepsilon\).

Claim. \(\displaystyle{\lim_{x\to 0} \frac{2x}{x(x-3)}=-\frac{2}{3}}.\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \[\delta=\min\left\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2},1\right\}.\] Let \(x\in (-\infty,0)\cup(0,3)\cup(3,\infty)\) such that \(0<|x-0|<\delta\). By our choice of \(\delta\) we have \(|x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\) We also see that \(|x|<1\) and hence \(|x-3|>2.\) Using this we have

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}<\frac{1}{2}.\]

Finally, we compute

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right| = \left|\frac{2}{x-3} +\frac{2}{3}\right| = \left|\frac{6}{3(x-3)} +\frac{2(x-3)}{3(x-3)}\right|= \left|\frac{2x}{3(x-3)}\right|\]

\[ = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\leq \frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon}{2} = \frac{\varepsilon}{6}<\varepsilon.\]

Practice Problem. Prove that \(\displaystyle{\lim_{x\to 2}x^2=4}\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \[\delta=\min\left\{\frac{\varepsilon}{10},1\right\}.\]

Let \(x\in \R\) such that \(0<|x-2|<\delta\) be arbitrary. Since \(|x-2|<1\) we see that

\[-1<x-2<1\]

and hence

\[3<x+2<5.\]

This implies \(|x+2|<5\), and hence

\[\left|x^2-4\right| = |x+2||x-2|\leq 5\delta \leq 5\cdot\frac{\varepsilon}{10} = \frac{\varepsilon}{2} <\varepsilon.\]

Lecture 29

By John Jasper

Lecture 29

- 213