Lecture 30:

Limits of Functions

Definition 4.1.1. Let \(A\subseteq\R\). A point \(c\in\R\) is a cluster point of \(A\) if for every \(\delta>0\) there exists at least one point \(x\in A\) such that \(x\neq c\) and \(|x-c|<\delta.\)

Example. Show that \(0\) is a cluster point of the set \((-1,1)\).

Answer. Let \(\delta>0\) be given. Set \(x=\min\{\frac{\delta}{2},\frac{1}{2}\}.\) It is clear that \(x>0\) and \(x\leq\frac{1}{2}<1.\) Hence, \(x\in (-1,1)\) and \(x\neq 0\). Finally

\[|x-0| = |x| = x\leq\frac{\delta}{2}<\delta.\]

Thus, for any \(\delta>0\) we have produced a number \(x\in(-1,1)\) such that \(x\neq 0\) and \(|x-0|<\delta\).

Definition 4.1.4. Let \(A\subseteq\R\), and let \(c\) be a cluster point of \(A\). For a function \(f: A\to\R\), a real number \(L\) is said to be the limit of \(f\) at \(c\) if, given any \(\varepsilon>0\), there exists \(\delta>0\) such that if \(x\in A\) and \(0<|x-c|<\delta\), then \(|f(x)-L|<\varepsilon.\)

Example. Consider the function \(f:(0,1]\to\R\) given by \(f(x) = x.\)

Steps in a proof.

1) Take an arbitrary \(\varepsilon>0\): Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given.

2) Choose a \(\delta>0\) that works: Set \(\delta = \varepsilon\).

4) Show that \(|f(x)-L|<\varepsilon\). By our choice of \(\delta\) we have \(|x|<\varepsilon,\) and hence \[|f(x) - 0| = |x|<\varepsilon.\]

3) Take an arbitrary \(x\) in the domain such that \(0<|x-c|<\delta\):

Let \(x\in (0,1]\) such that \(0<|x-0|<\delta\) be given.

Claim. \(0\) is the limit of \(f\) at \(0.\)

Example. Consider the function \(f:(0,1]\to\R\) given by \(f(x) = x.\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \(\delta = \varepsilon\). Let \(x\in (0,1]\) such that \(0<|x-0|<\delta\) be given. By our choice of \(\delta\) we have \(|x|<\varepsilon,\) and hence

\[|f(x) - 0| = |x|<\varepsilon.\ \Box\]

Claim. \(0\) is the limit of \(f\) at \(0.\)

Example. Prove that \(\displaystyle{\lim_{x\to 2}x^2=4}\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \[\delta=\min\left\{\frac{\varepsilon}{10},1\right\}.\]

Let \(x\in \R\) such that \(0<|x-2|<\delta\) be arbitrary. Since \(|x-2|<1\) we see that

\[-1<x-2<1\]

and hence

\[3<x+2<5.\]

This implies \(|x+2|<5\), and hence

\[\left|x^2-4\right| = |x+2||x-2|\leq 5\delta \leq 5\cdot\frac{\varepsilon}{10} = \frac{\varepsilon}{2} <\varepsilon.\]

Claim. \(\displaystyle{\lim_{x\to 0} \frac{2x}{x(x-3)}=-\frac{2}{3}}.\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \[\delta=\min\left\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2},1\right\}.\] Let \(x\in (-\infty,0)\cup(0,3)\cup(3,\infty)\) such that \(0<|x-0|<\delta\). By our choice of \(\delta\) we have \(|x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\) We also see that \(|x|<1\) and hence \(|x-3|>2.\) Using this we have

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}<\frac{1}{2}.\]

Finally, we compute

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right| = \left|\frac{2}{x-3} +\frac{2}{3}\right| = \left|\frac{6}{3(x-3)} +\frac{2(x-3)}{3(x-3)}\right|= \left|\frac{2x}{3(x-3)}\right|\]

\[ = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\leq \frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon}{2} = \frac{\varepsilon}{6}<\varepsilon.\]

How did we figure that out?

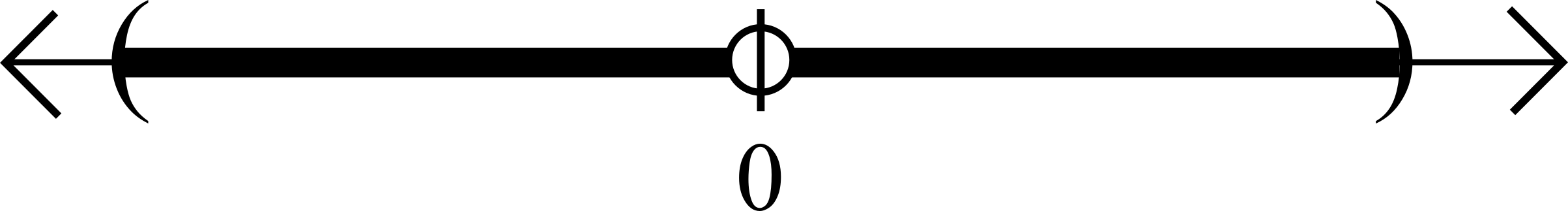

We know that for each \(\varepsilon>0\) we have to find a \(\delta>0\) such that every \(x\) in

\[-\delta\]

\[\delta\]

That is, every \(x\) that satisfies \(0<|x-0|<\delta\) we must have

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right|<\varepsilon\]

Thus, we look closely at the expression on the left above:

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right|= \left|\frac{2x}{3(x-3)}\right| = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\]

What can we say about \(\dfrac{1}{|x-3|}\) and \(|x|\) when \(\delta\) is small?

If \(\delta\) is very small, then \(x\approx 0\) and hence

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}\approx\frac{1}{3}\quad\text{ and }\quad|x|\approx 0.\]

Let's actually be precise: If \(\delta<1\) then \(|x|<\delta\) implies that \(-1<x<1.\)

This implies \(-4<x-3<-2\), and hence \(|x-3|>2\). Rearranging this inequality we have

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}<\frac{1}{2}.\]

Thus, if we choose our \(\delta\) to be less than \(1\) then we will have

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right|= = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\leq \frac{1}{3}|x|\]

From here, we see that it is enough to choose \(\delta\) to be less than \(\varepsilon\).

Claim. \(\displaystyle{\lim_{x\to 0} \frac{2x}{x(x-3)}=-\frac{2}{3}}.\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \[\delta=\min\left\{\frac{\varepsilon}{2},1\right\}.\] Let \(x\in (-\infty,0)\cup(0,3)\cup(3,\infty)\) such that \(0<|x-0|<\delta\). By our choice of \(\delta\) we have \(|x|<\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\) We also see that \(|x|<1\) and hence \(|x-3|>2.\) Using this we have

\[\frac{1}{|x-3|}<\frac{1}{2}.\]

Finally, we compute

\[\left|\frac{2x}{x(x-3)} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)\right| = \left|\frac{2}{x-3} +\frac{2}{3}\right| = \left|\frac{6}{3(x-3)} +\frac{2(x-3)}{3(x-3)}\right|= \left|\frac{2x}{3(x-3)}\right|\]

\[ = \frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{|x-3|}|x|\leq \frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon}{2} = \frac{\varepsilon}{6}<\varepsilon.\]

Example. Prove that \(\displaystyle{\lim_{x\to 3}(x^2-2x)=3}\)

Proof. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. Set \[\delta=\min\left\{\frac{\varepsilon}{10},1\right\}.\]

Let \(x\in \R\) such that \(0<|x-3|<\delta\) be arbitrary. Since \(|x-3|<1\) we see that

\[-1<x-3<1\]

and hence

\[3<x+1<5.\]

This implies \(|x+1|<5\), and hence

\[\left|x^2-2x-3\right| = |x+1||x-3|\leq 5\delta \leq 5\cdot\frac{\varepsilon}{10} = \frac{\varepsilon}{2} <\varepsilon.\]

Lecture 30

By John Jasper

Lecture 30

- 228