Characterising the Variability of the Black Hole at the Centre of our Galaxy using Multi-Output Gaussian Processes

Shih Ching Fu

shihching.fu@postgrad.curtin.edu.au

Supervisors:

Dr Arash Bahramian, Dr Aloke Phatak,

Dr James Miller-Jones, Dr Suman Rakshit

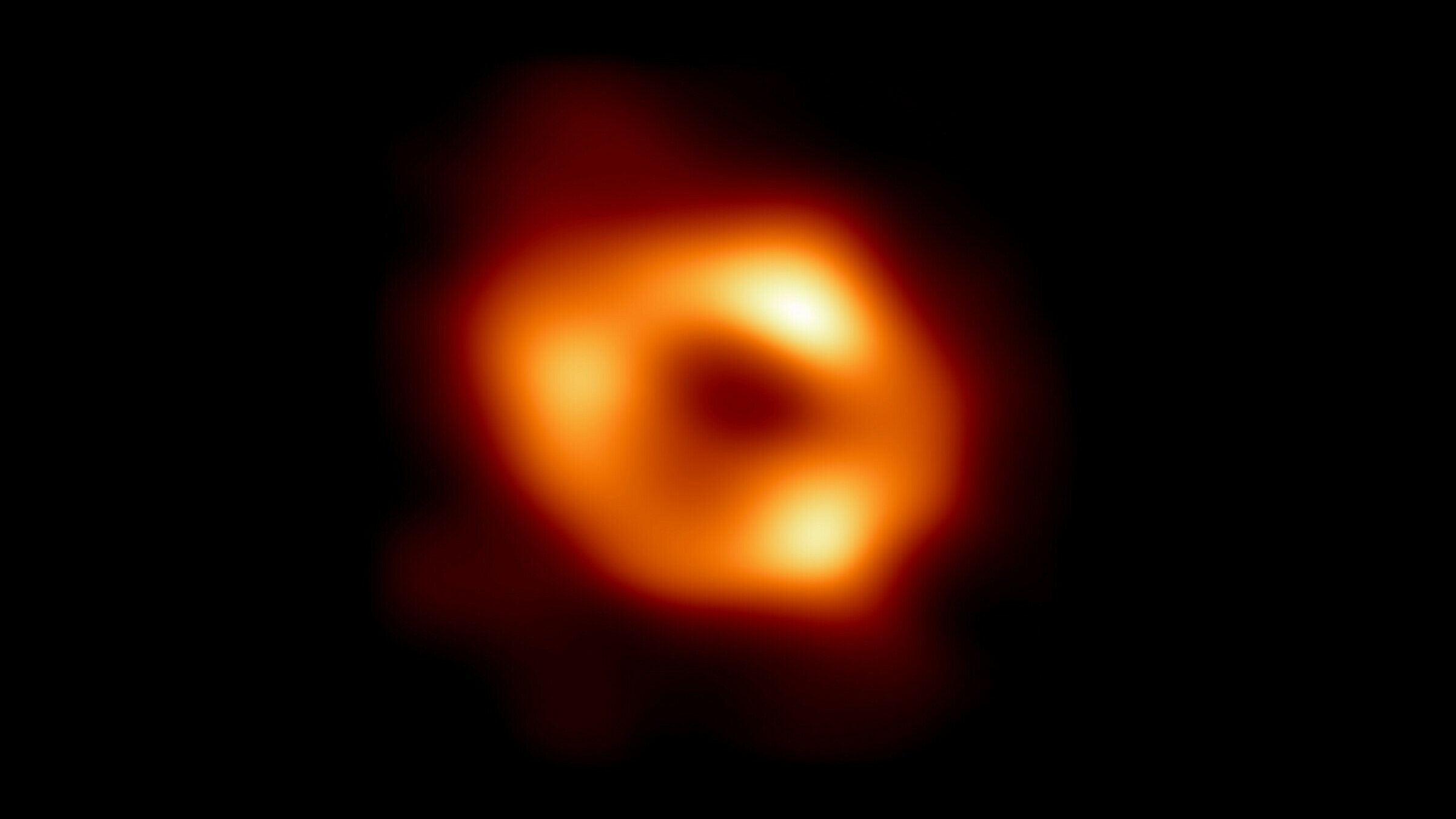

Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*)

- Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) at the centre of the Milky Way.

- 4 million solar masses.

- ~27,000 ly from Earth

- Image created from observations taken in 2017 by the Event Horizon Telesope (EHT) Collaboration.

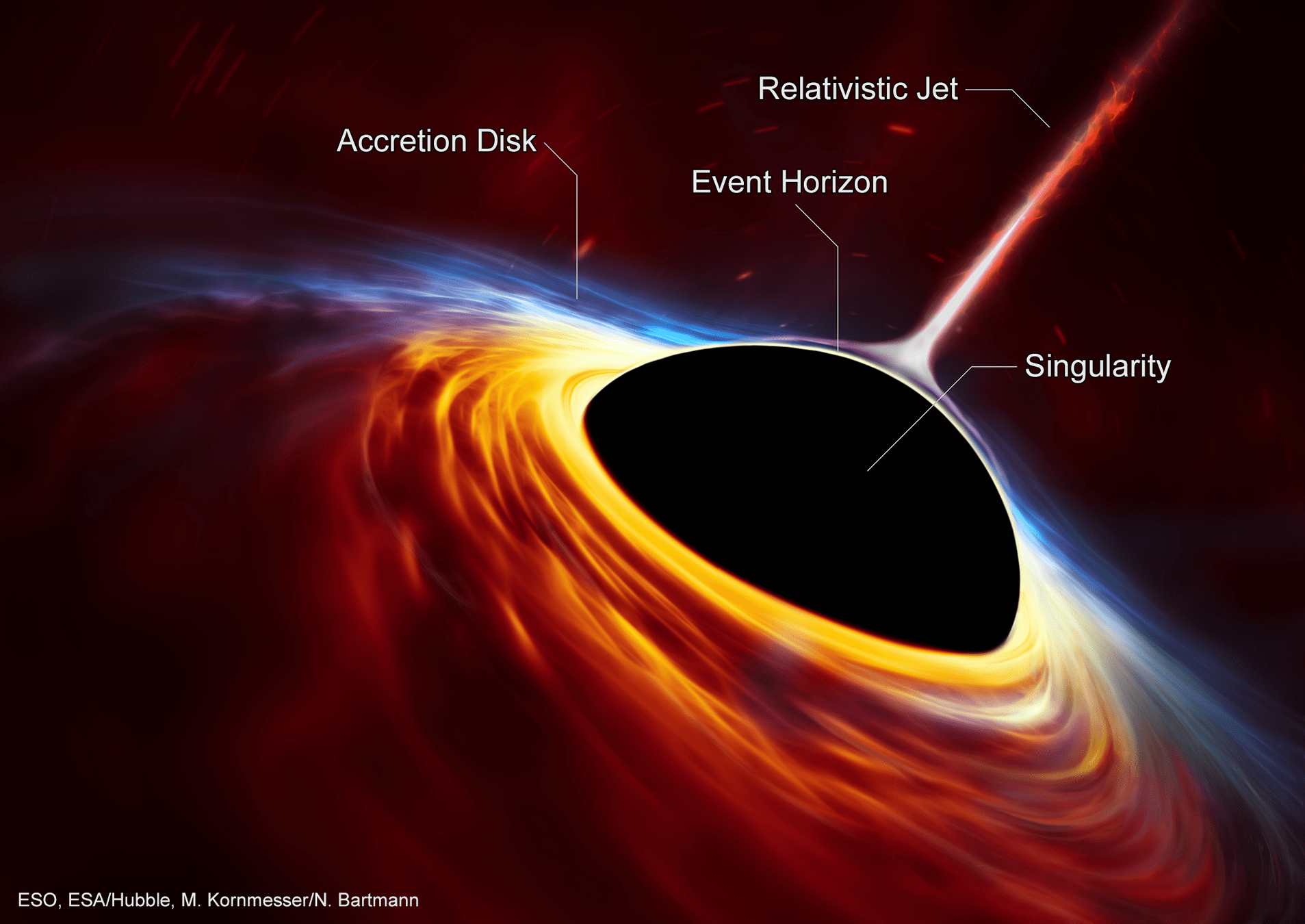

Anatomy of a Black Hole

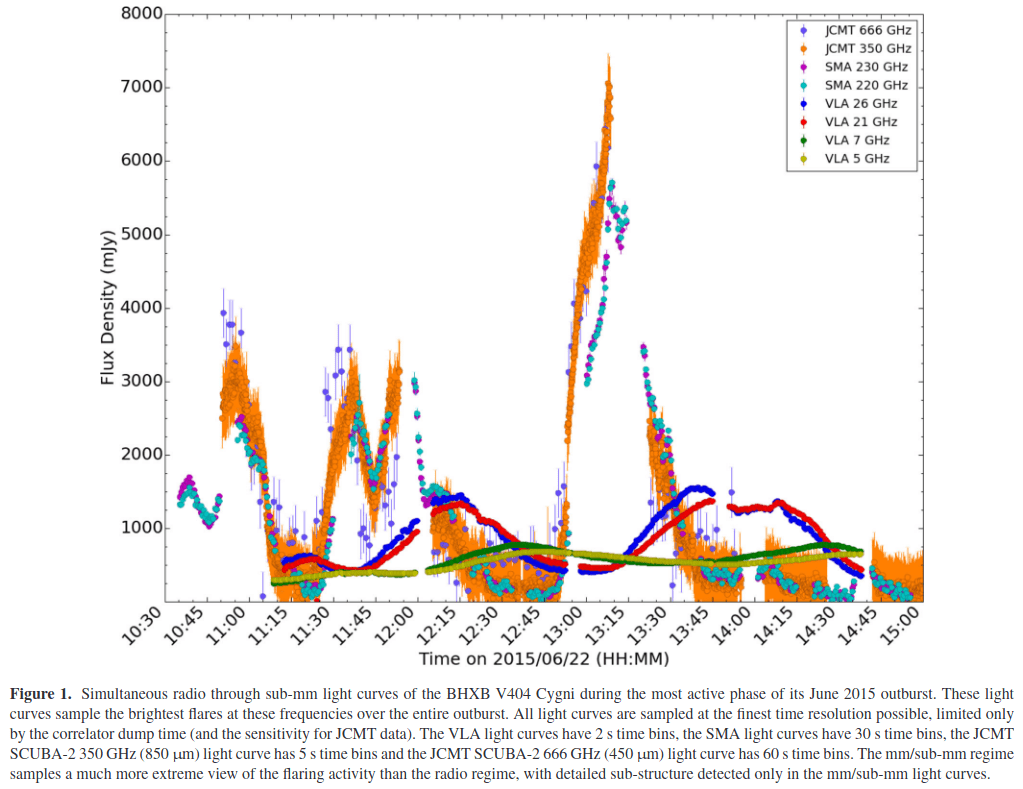

Time domain astronomy

- Estimate the characteristic timescales of the variability in the black hole emissions.

- Characterise the relationship between emissions of different wavelengths, e.g, time delay between bands.

Credit: Tetarenko et al. (2017)

Black hole X-ray binary

V404 Cygni

Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA)

- Chilean Atacama Desert at 5000m elevation.

- 66 high-precision dish antennas: 54 x 12m and 12 x 7m across.

- Radio and infrared.

- Member site of EHT Collaboration.

Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOH/NRAO)

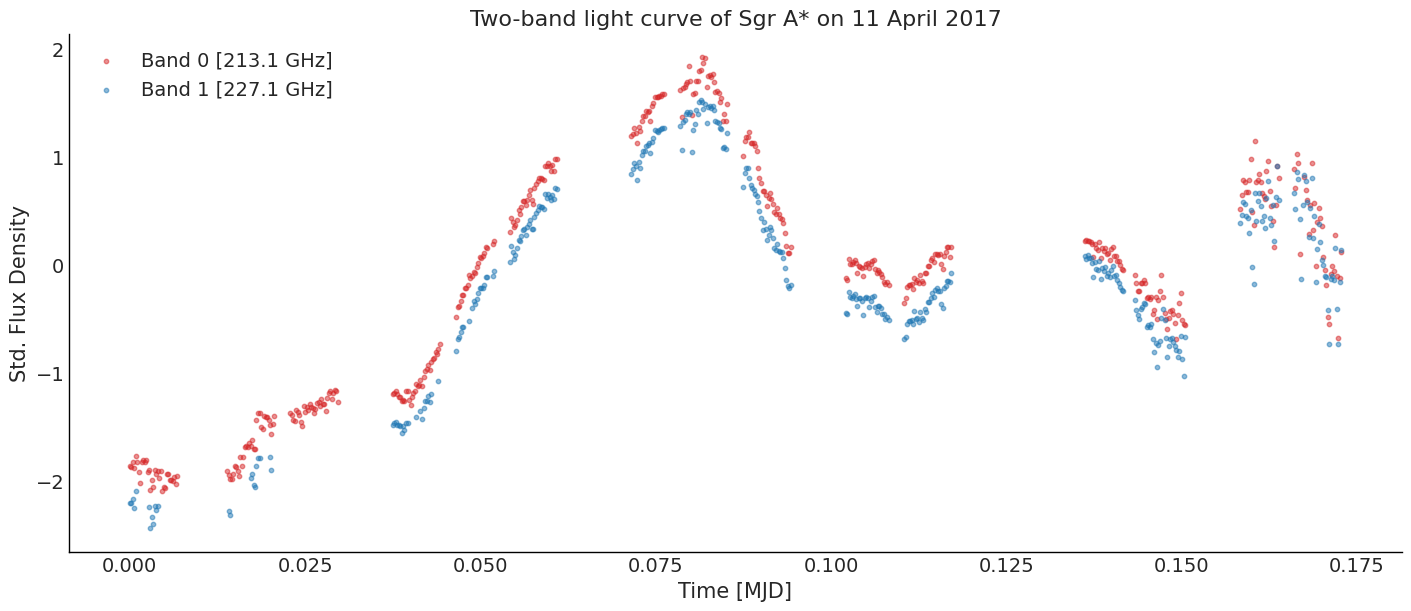

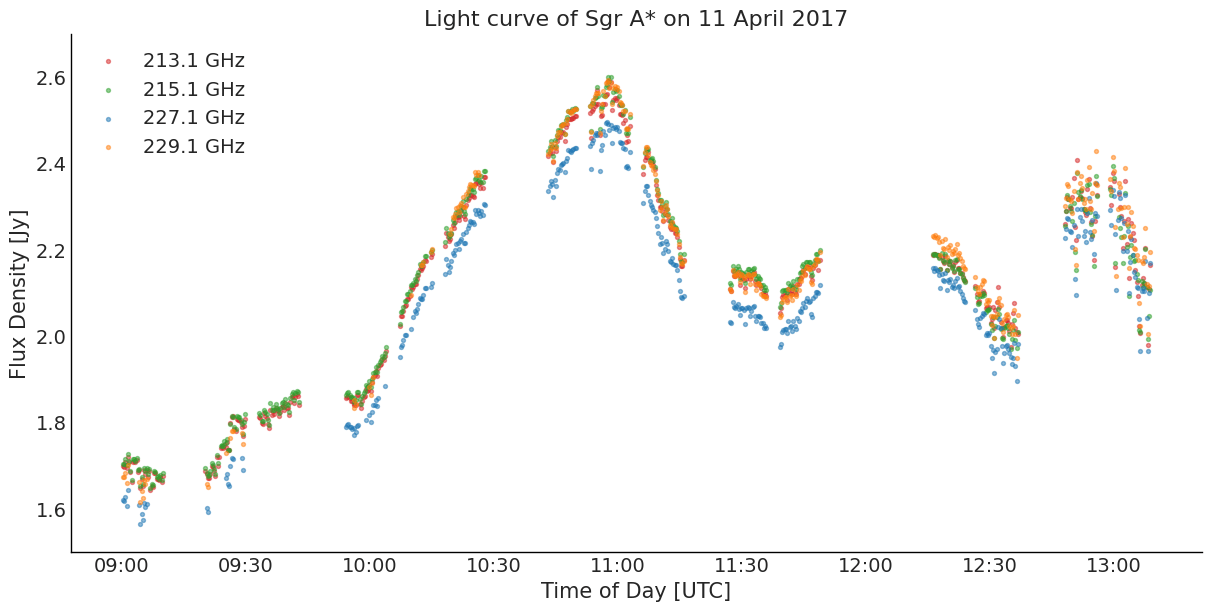

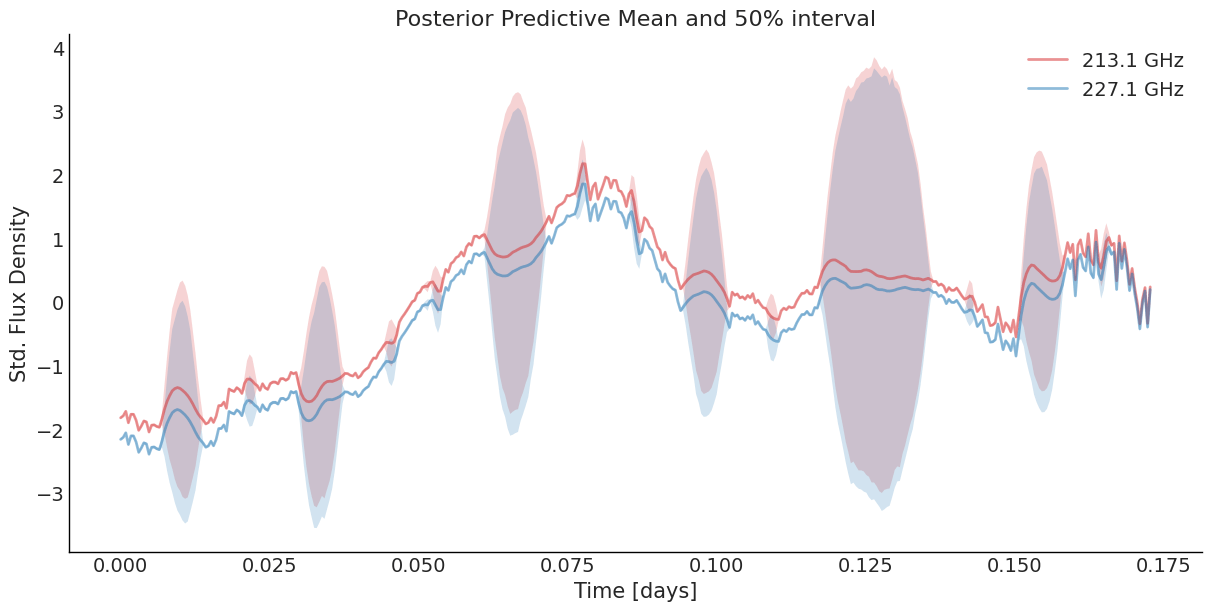

Multi-band Light Curve

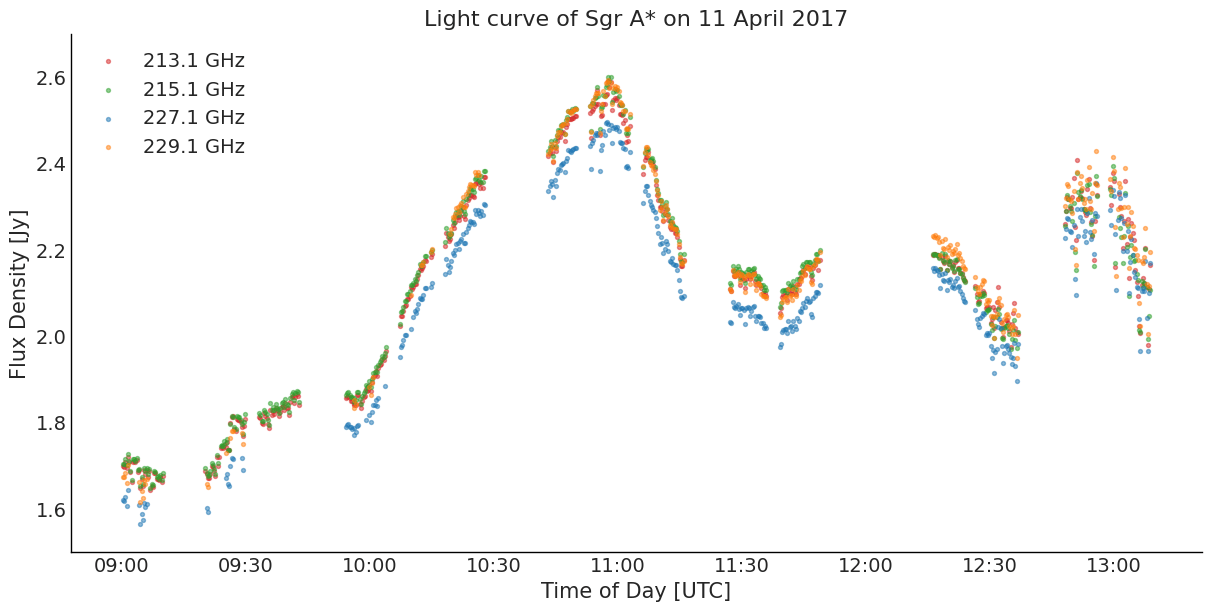

Two-band Light Curve

Gaussian Processes (GPs)

Extend multivariate Gaussian to 'infinite' dimensions.

- Mean function, \(\mu(t)\)

- Covariance or kernel function, \( \kappa(t,t'; \boldsymbol{\theta}) \)

where \(\mu = \mu(t)\) and \( K_{ij} = \kappa(t_i, t_j; \boldsymbol{\theta}) \), for \( i,j = 1, 2, \dots \)

Rather than specify a fixed covariance matrix with fixed dimensions, compute covariances using the kernel function.

Multivariate Normal

Y is a vector of n Gaussian distributed random variables.

where \(\boldsymbol\mu = (\mu_1, \dots, \mu_n)\) and \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\) is a \(n \times n \) covariance matrix.

- Symmetric, positive semi-definite matrix.

- Linear combinations are also valid covariance matrices.

"Single-output" GP

Multiple Output GP (MOGP)

\(1 \times (n_1 + n_2)\)

\((n_1 + n_2) \times (n_1 + n_2)\)

Cross-covariance

\(\boldsymbol{K}_{\boldsymbol{f},\boldsymbol{f}}\)

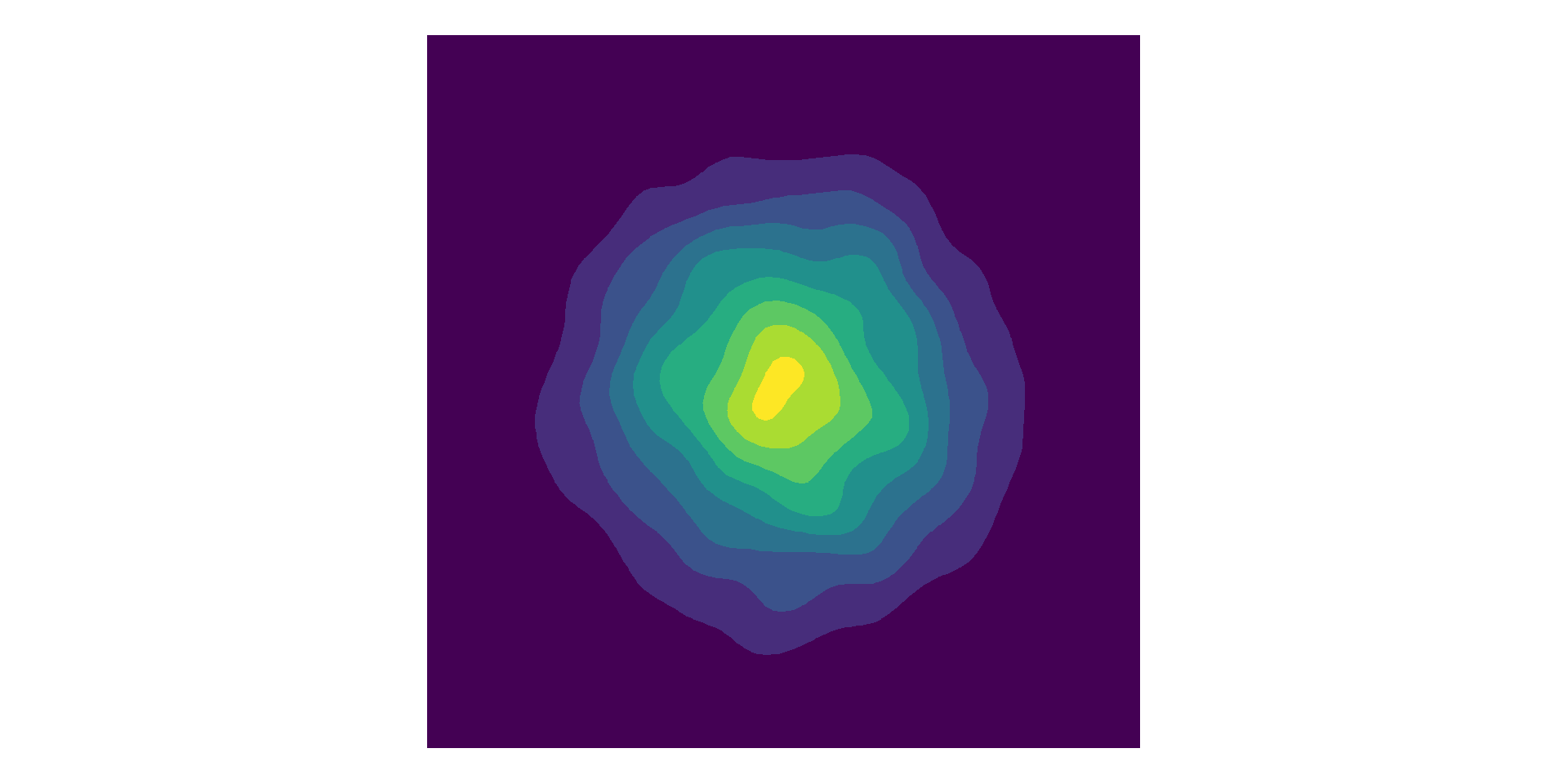

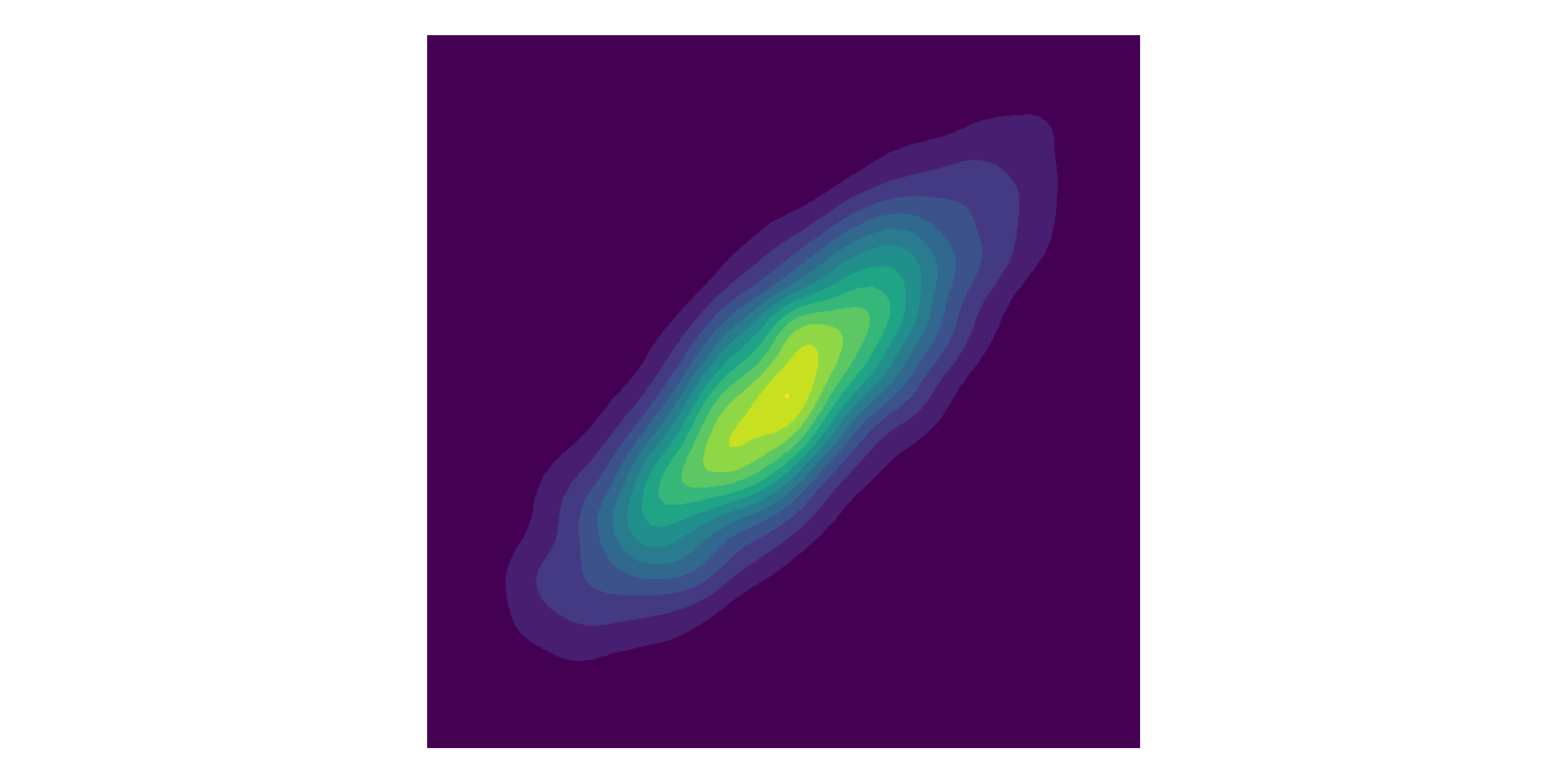

MOGP Kernels

- Choose a cross-covariance function \( \operatorname{cov}[f_1(\boldsymbol{x}),f_2(\boldsymbol{x}')]\) such that \( \boldsymbol{K}_{\boldsymbol{f},\boldsymbol{f}}\) is a valid covariance matrix, i.e., positive semi-definite.

- Start with "separable" kernels where \(\boldsymbol{K}_{\boldsymbol{f},\boldsymbol{f}}\) is decomposed into submatrices.

\(\boldsymbol{K}_{\boldsymbol{f},\boldsymbol{f}}\)

?

?

Semiparametric Latent Factor Model (SLFM)

Fit each band as a linear combination of two latent GPs,

where \(d = 1,2,3,4\) output bands and \(q = 1,2\) latent processes

Alternatively,

Semiparametric Latent Factor Model (SLFM)

Co-regionalisation Matrices

Kronecker product

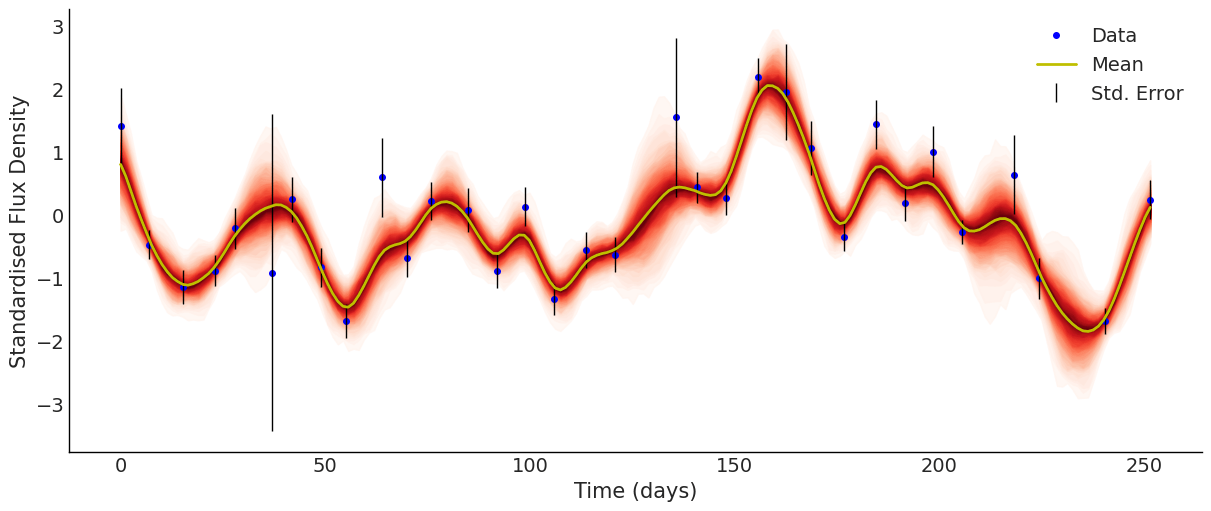

Latent Process Model

Parameter model

Matern 3/2

Squared Exponential

Interested in the length scale hyperparameters \(\ell_{\textrm{M32}}\) and \(\ell_{\textrm{SE}}\)

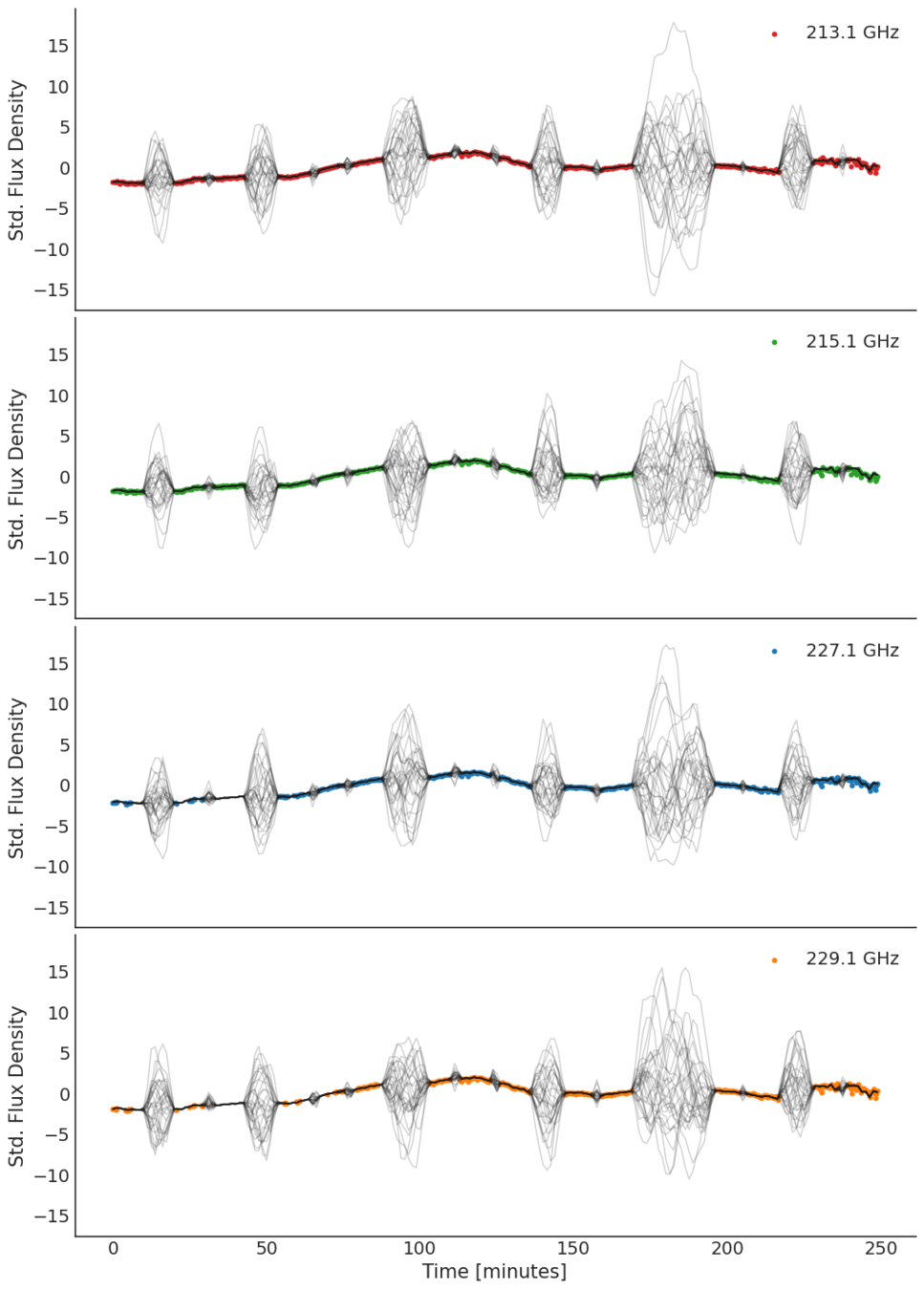

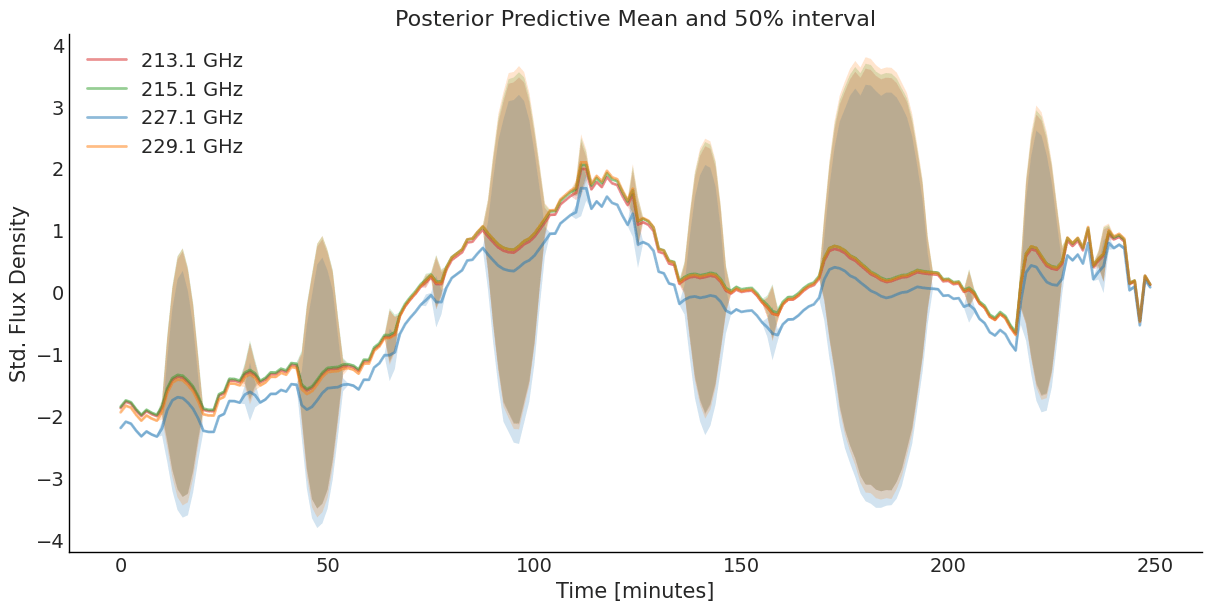

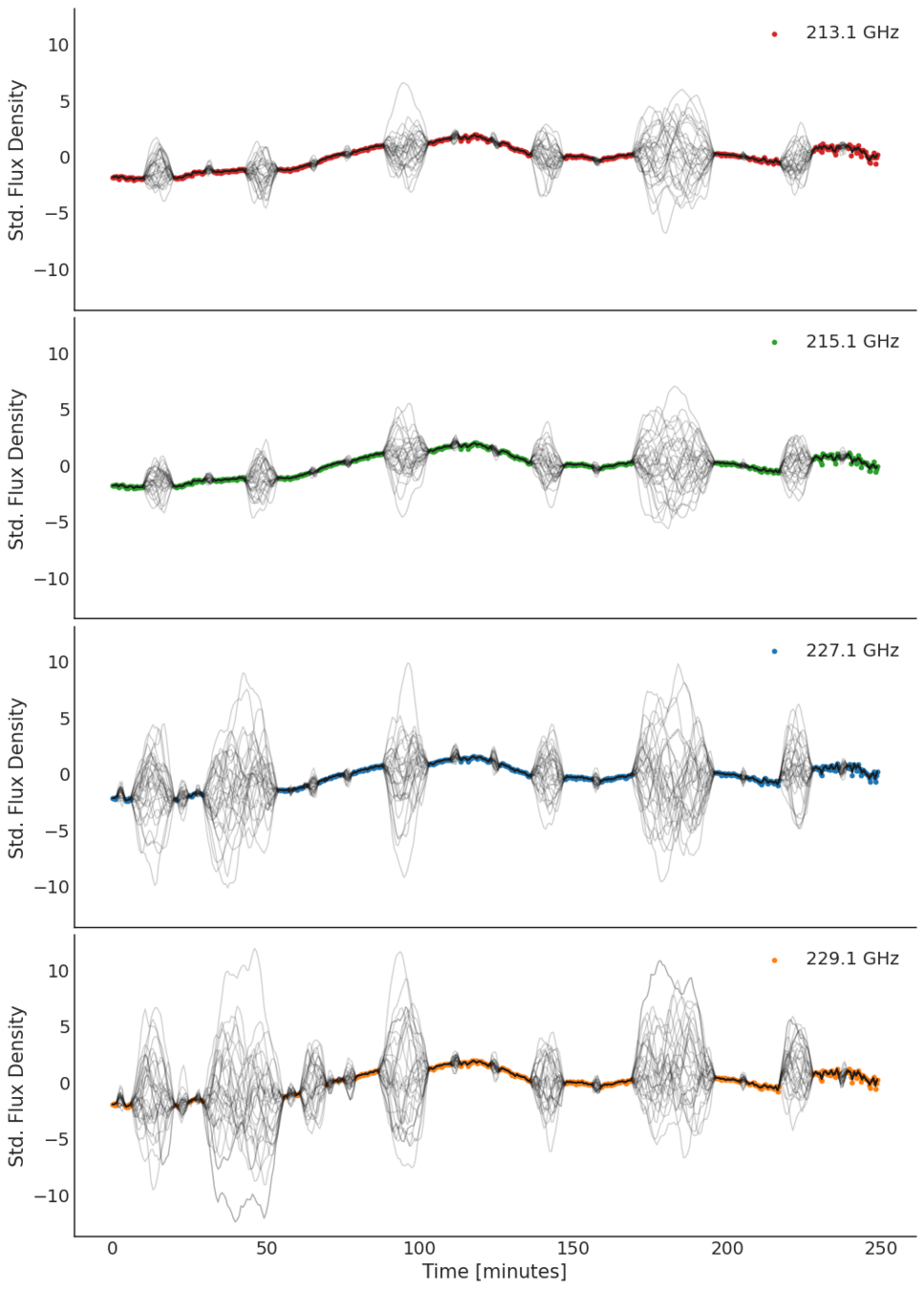

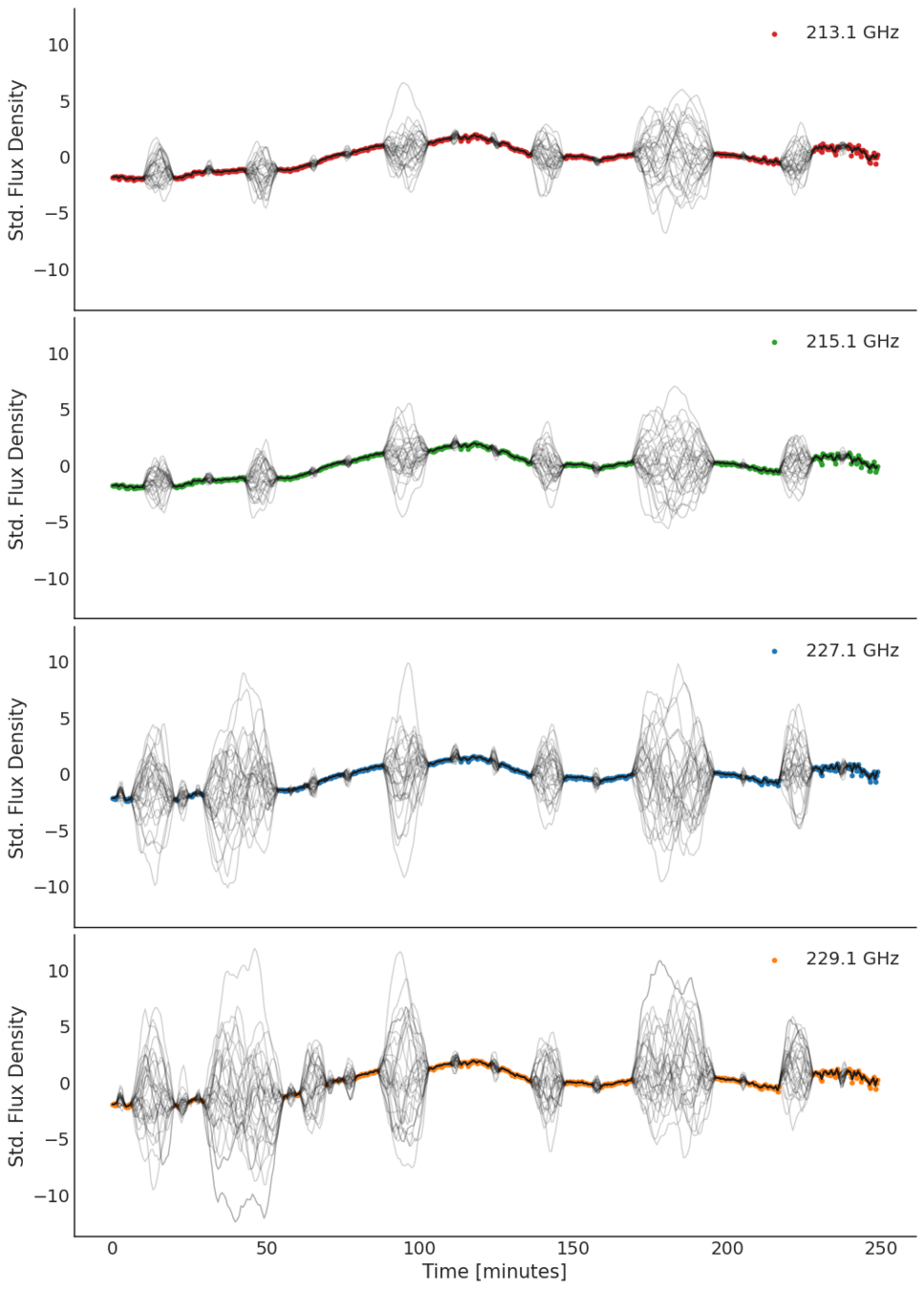

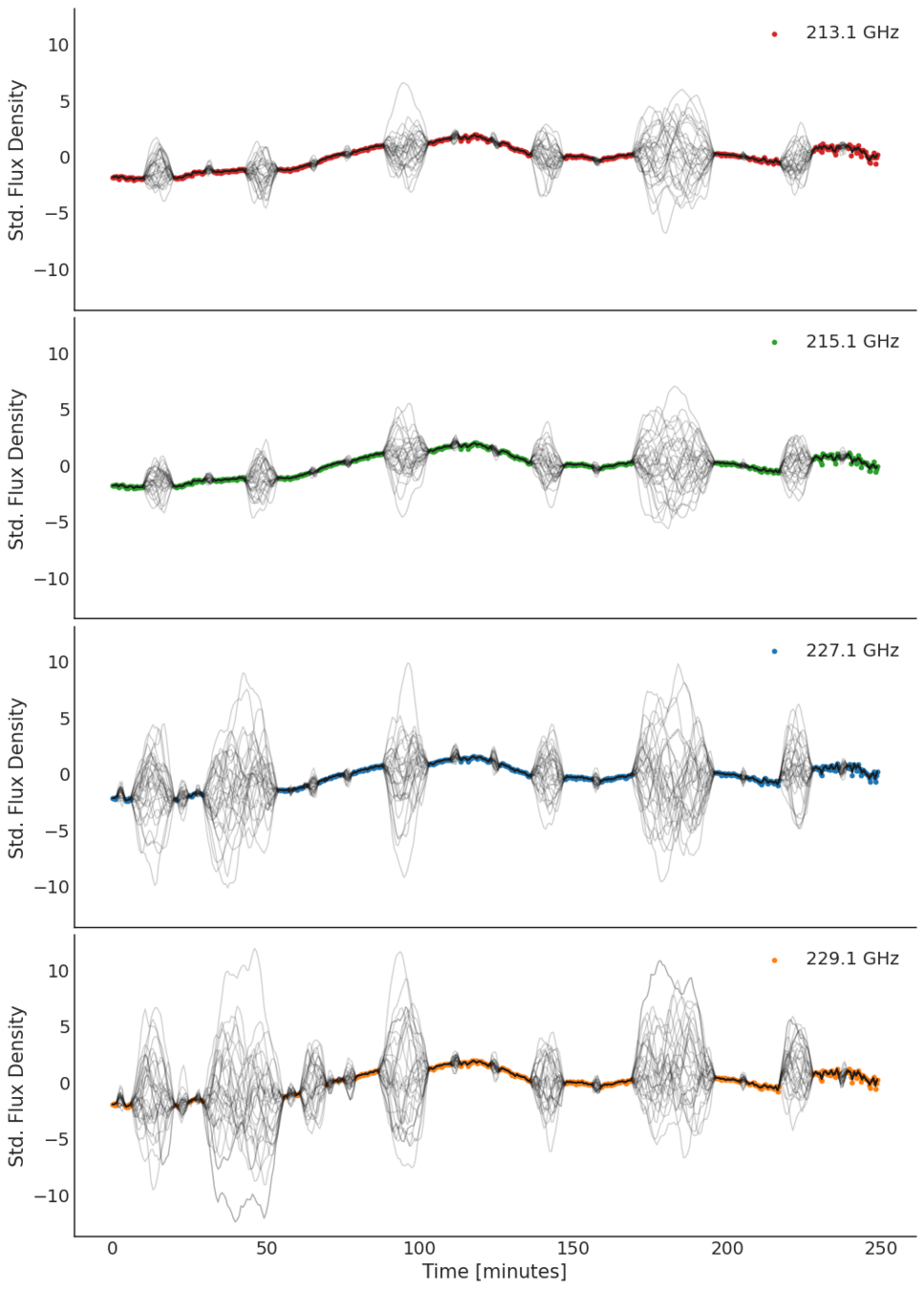

Four-band Light Curve

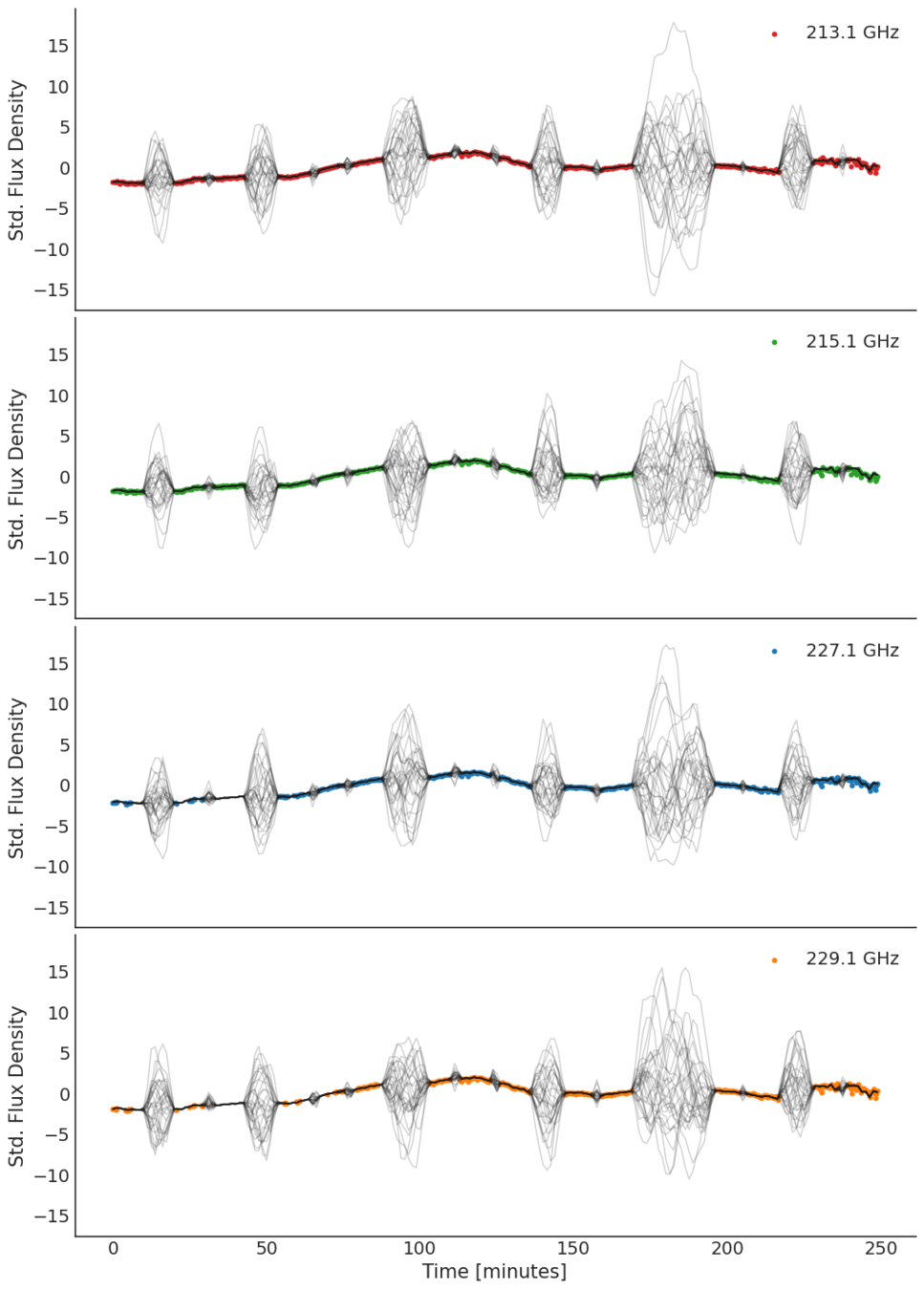

SLFM Fitting Result

\(\ell_{M32}\) = 7.20 minutes (94% HDI 4.32, 8.64)

\(\ell_{SE}\) = 33.1 minutes (94% HDI 27.4, 38.9)

NB: Fitted curves are perfectly aligned.

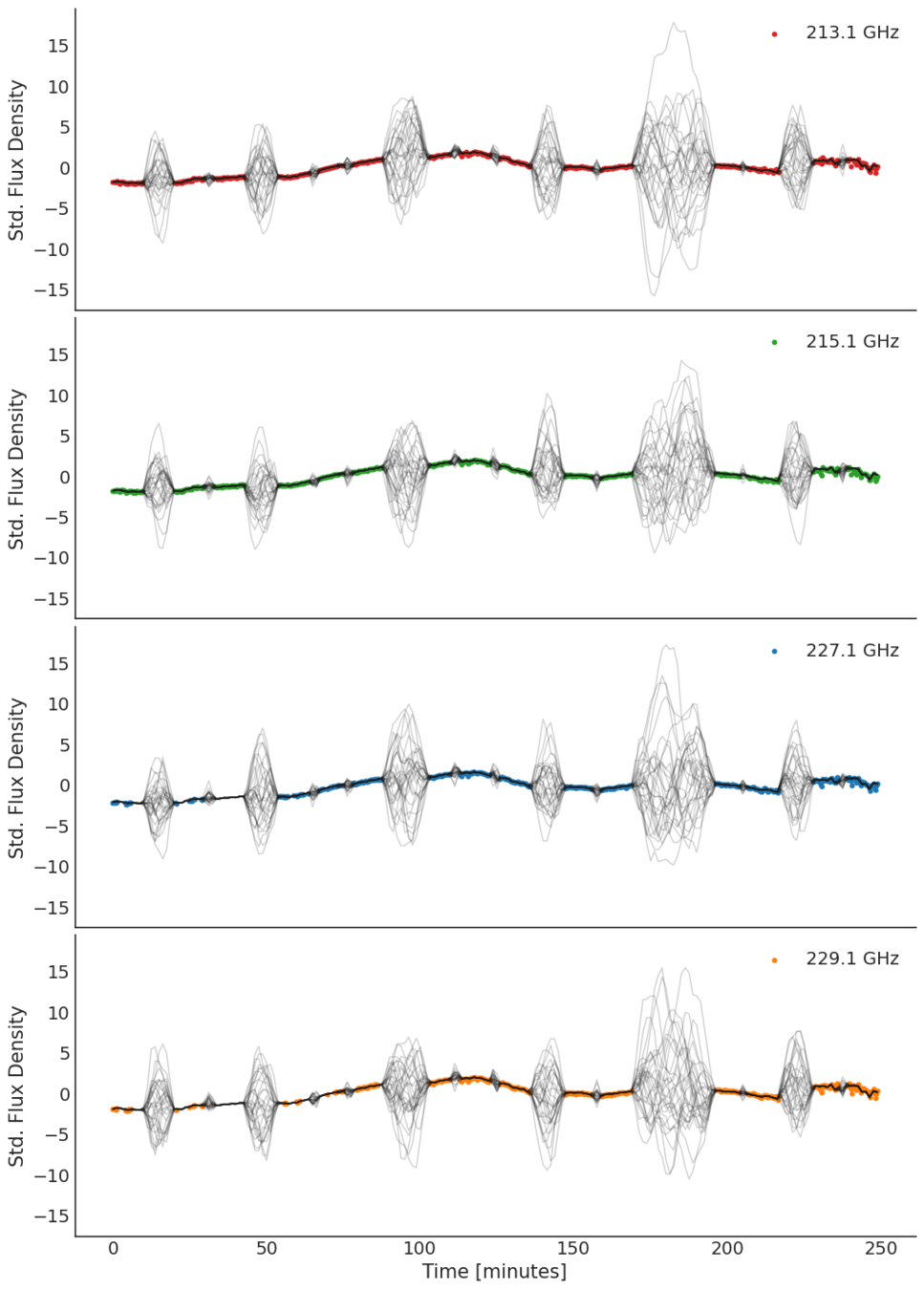

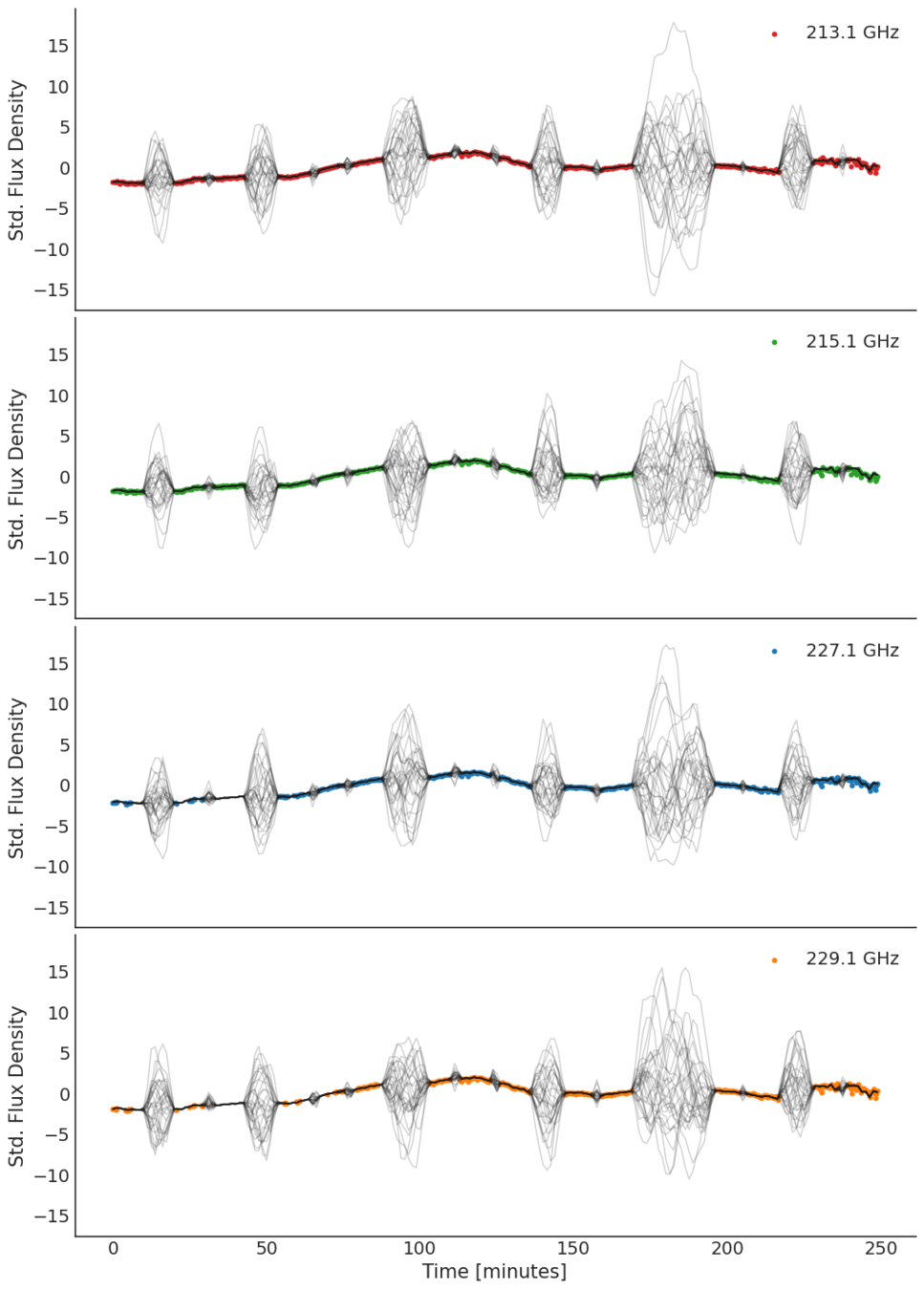

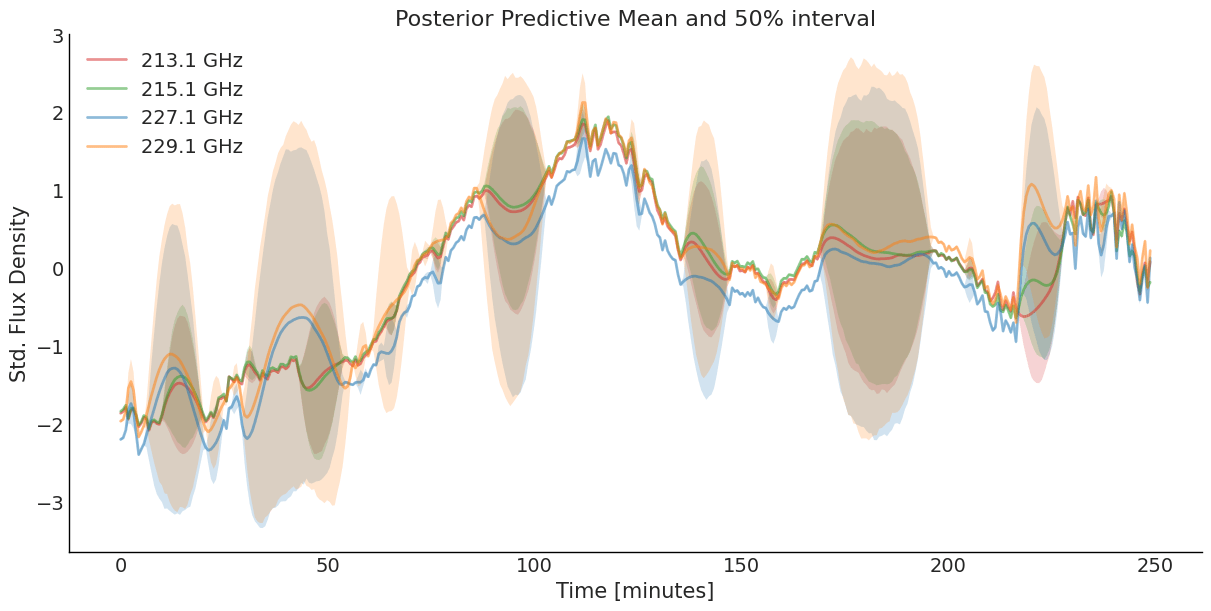

SLFM Result

\(\ell_{M32}\) = 7.23 minutes (94% HDI 5.04, 9.65)

\(\ell_{SE}\) = 25.6 minutes (94% HDI 18.9, 30.2)

NB: Fitted curves are perfectly aligned.

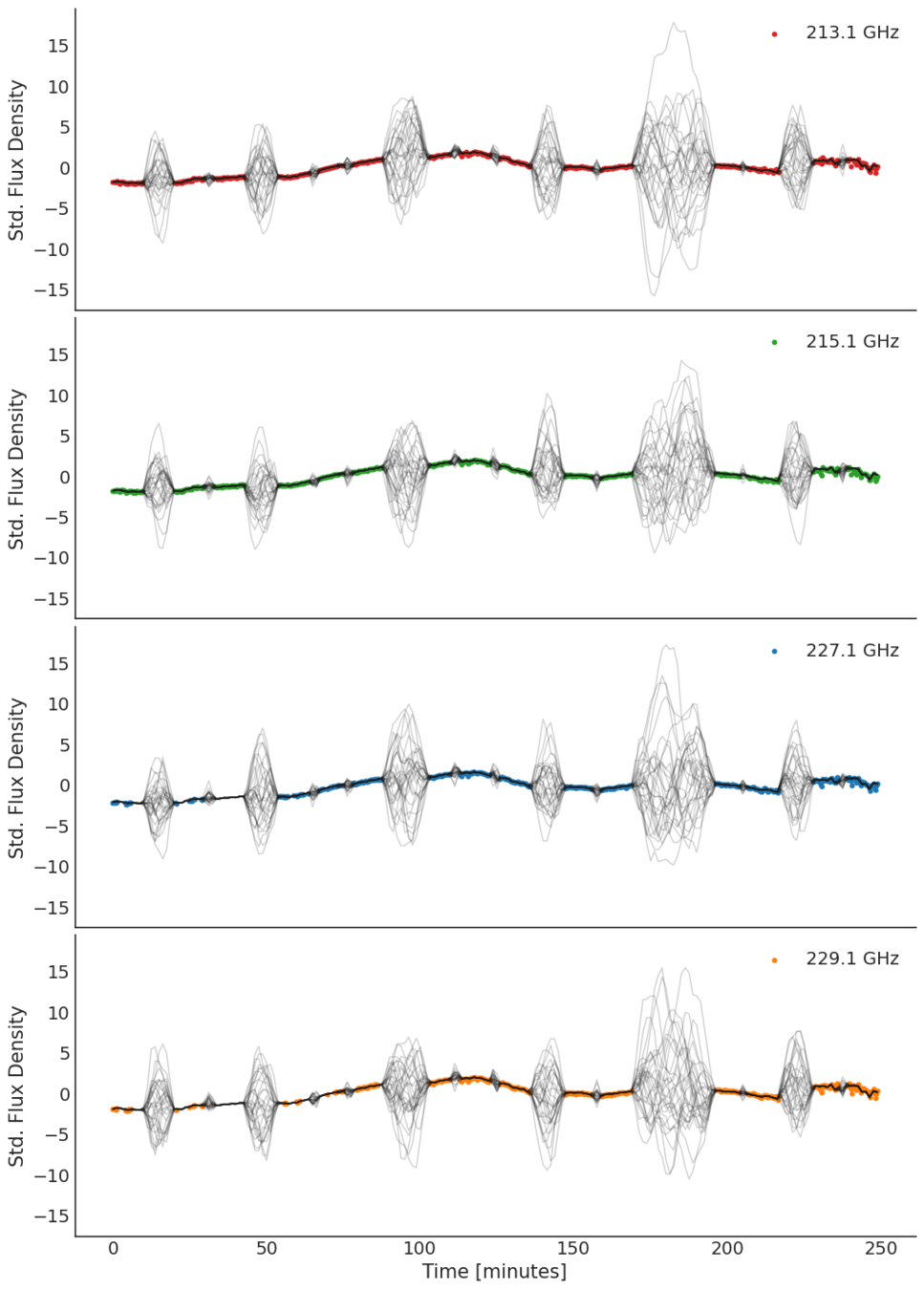

SLFM Fitting Result

\(\ell_{M32}\) = 7.20 minutes (94% HDI 4.32, 8.64)

\(\ell_{SE}\) = 33.1 minutes (94% HDI 27.4, 38.9)

NB: Fitted curves are perfectly aligned.

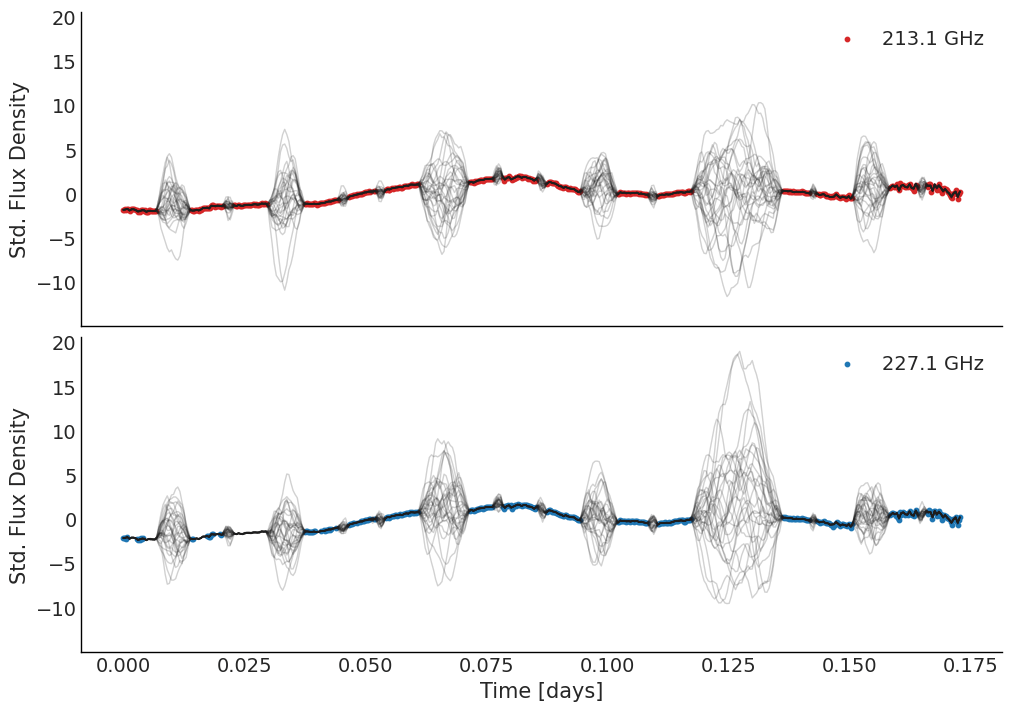

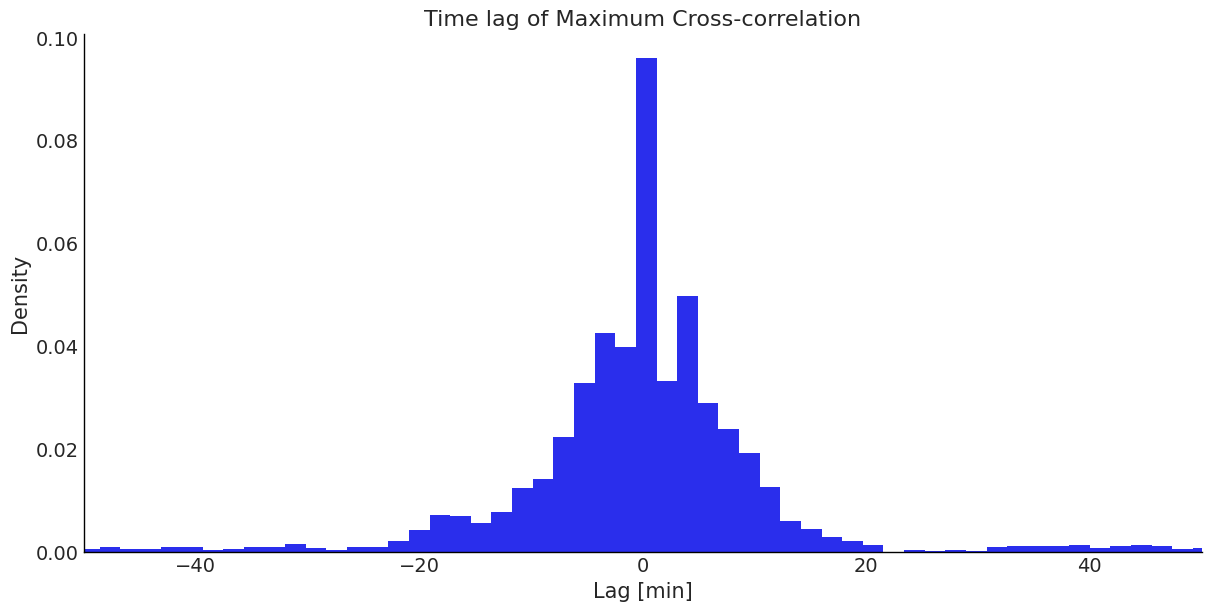

Naive Estimation of Band Delay

- Cross-correlation is a commonly used method to identify the lag between time series.

- But unevenly sampled data complicates this.

- Try resampling the data with a GP model and then compute cross-correlation between posterior predictive samples.

- Separable MOGPs obliterate time-delay information.

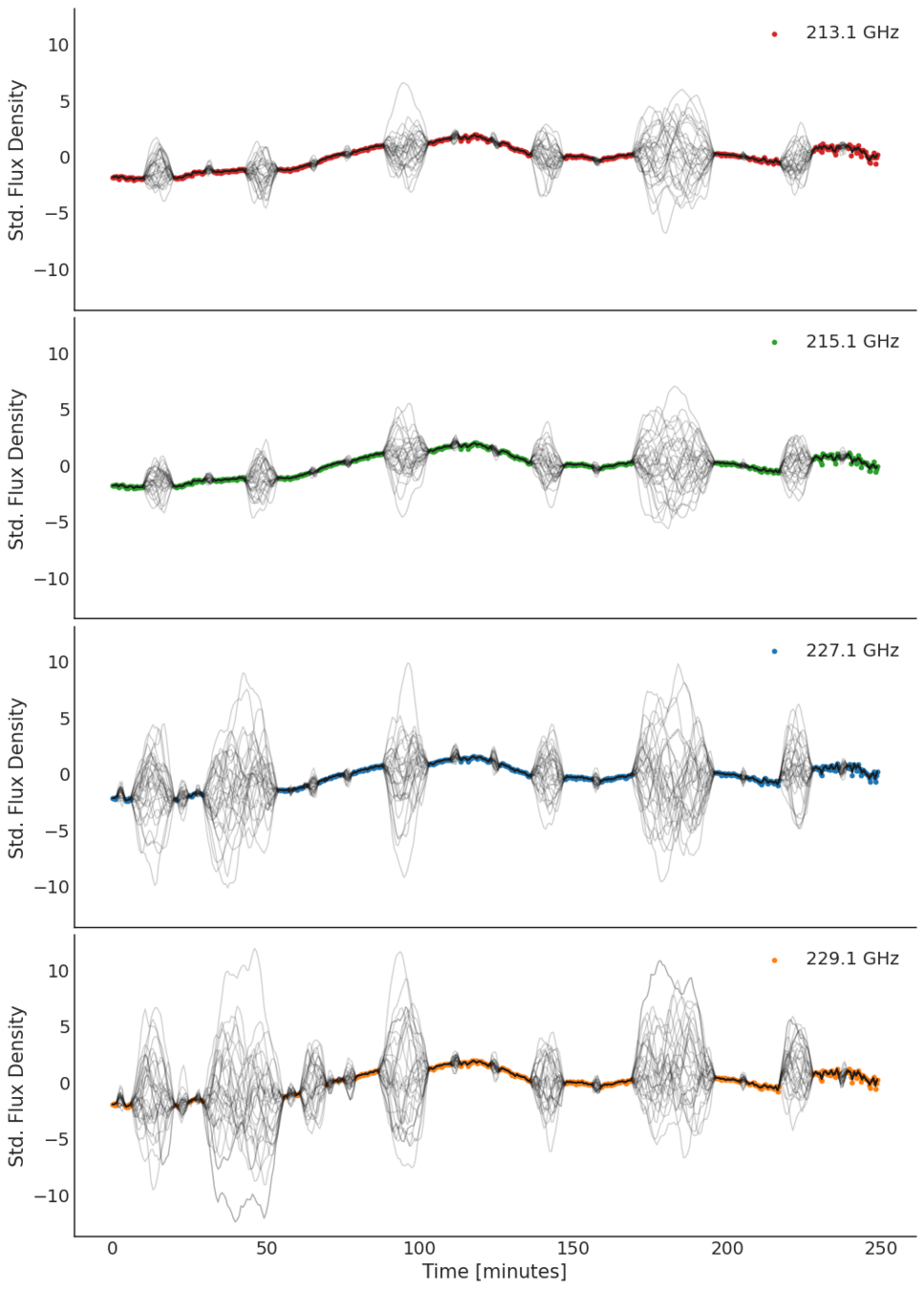

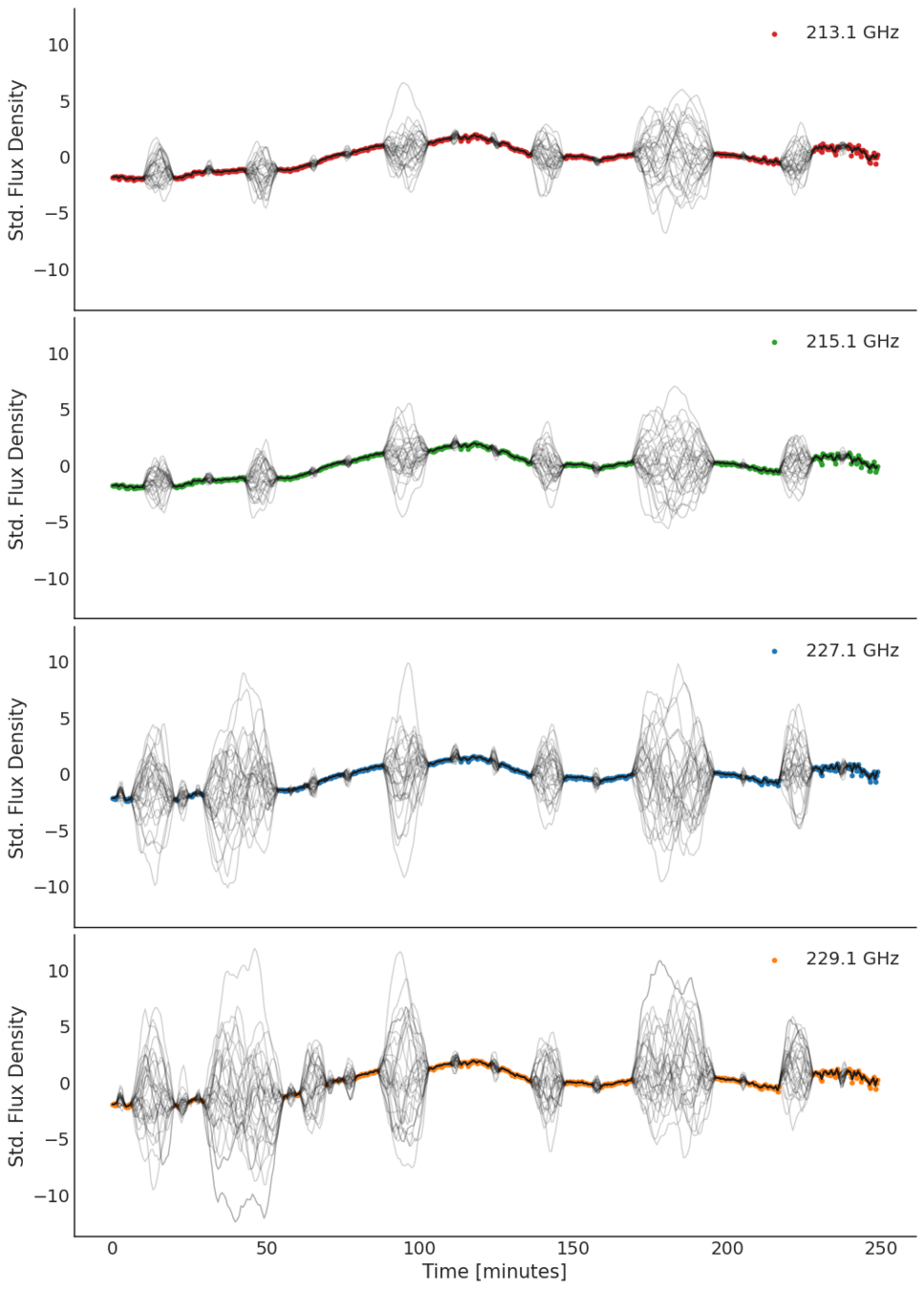

4-band

Light Curve

Fit 4 univariate GPs

Cross-correlation on posterior samples

Identify most likely time delay

Four Single-output GPs

Four Single-output GPs

Cross Correlation

- Results are poor, most lags at zero.

- Model the time-delay term explicitly!

- Considering Spectral Mixture Kernel MOGPs

"Stop using computer simulations as a substitute for thinking"

Quantitude Podcast, Season 4, Episode 7

Summary

- Multi-band light curves of Sgr A* with different sampling rates.

- Tried using MOGP regression to characterise the:

- time scale of variation, and

- time delays between bands.

- Found two characteristic time scales: 7.2 and 33.1 minutes.

- Separable kernels cannot be used to model the cross-band time delays; need to parameterise these explicitly.

- Navigating the literature between astronomy, astrophysics, statistics, and machine learning, has been tricky.

Characterising the Variability of the Black Hole at the Centre of our Galaxy using Multi-Output Gaussian Processes

By Shih Ching Fu

Characterising the Variability of the Black Hole at the Centre of our Galaxy using Multi-Output Gaussian Processes

The advent of large-scale surveys that observe thousands, if not millions, of sources puts the task of identifying novel candidates beyond the manual capability of astronomers. To automate the sifting of these sources at scale, a statistical approach can be used to characterise and classify promising candidates. Care must be taken, however, to not overfit to a particular object type or survey configuration so that processing can be applied across surveys without introducing statistical biases. In this work, I present a Gaussian process (GP) regression approach for statistically characterising light curves and demonstrate this approach on 5131 radio light curves from the ThunderKAT survey. The benefits of a GP approach include the implicit handling of data sparsity and irregular sampling, accommodating light curves of diverse shapes, and having astrophysically meaningful interpretations of the fitted model hyperparameters. Indeed, I found distinct regions in the amplitude hyperparameter space that point to a candidate's propensity to be a transient or variable source. Compared with variability metrics commonly used in radio astronomy, this approach has improved discriminatory power.

- 46