Applied

Microeconomics

Lecture 21

BE 300

Plan for Today

Price discrimination

Multi-part pricing

Coming Up

"Threat to Scholarly Communication" Case Due

Textbook reading 10.5-10.7

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination: when firms charge different prices to different customers for the same good, where the different prices are not based on cost differentials

Price Discrimination

The goal is to extract more consumer surplus.

For any given level of costs, this generate higher revenues (and thus higher profit).

Price Discrimination

For firms to be able to price discriminate, they MUST:

- Have some market power.

- Be able to infer consumers' willingness to pay (which must also be different across customers).

- Prevent arbitrage (re-sale among consumers).

Sometimes preventing arbitrage is very difficult or impossible.

Examples of price discrimination (successful or unsuccessful):

How do firms infer willingness to pay and prevent arbitrage?

Price Discrimination

Legal treatment in the US:

In the US, the Robinson Patman Act (1936) makes price discrimination from manufacturer to reseller or from distributor to retailer illegal under certain conditions.

Two main defenses:

- Cost justification (in which case it is not price discrimination)

- Meeting competition "in good faith"

The Robinson Patman Act has not been very popular with its enforcers (FTC, Justice) over the last decades

However, private suits continue...

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination to ultimate consumers is legal.

Only illegal aspects arise from “social” discrimination rules (based on race, age, gender, etc.)

Even here, there's a lot of flexibility.

Examples?

Price Discrimination

First degree ("perfect") price discrimination involves charging a different price to every consumer based on his or her exact willingness to pay.

This extracts all consumer surplus for the firm.

Any examples?

Price Discrimination

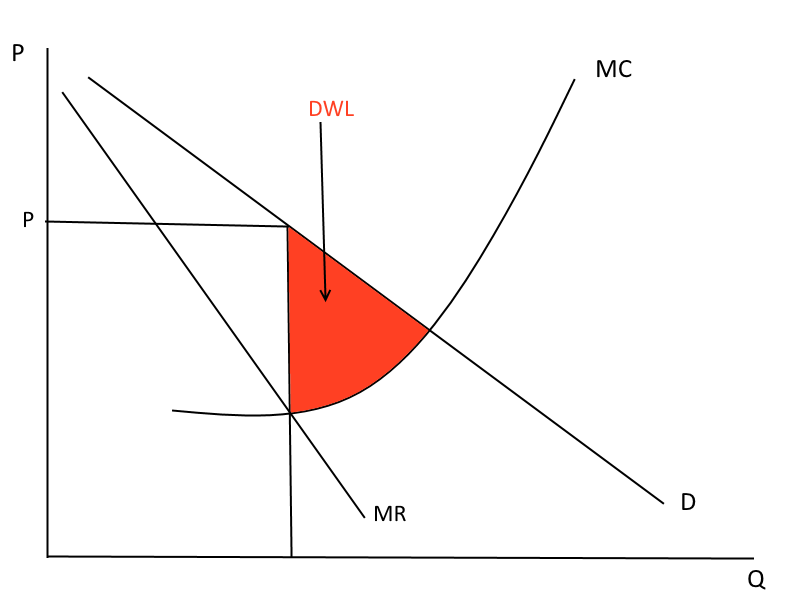

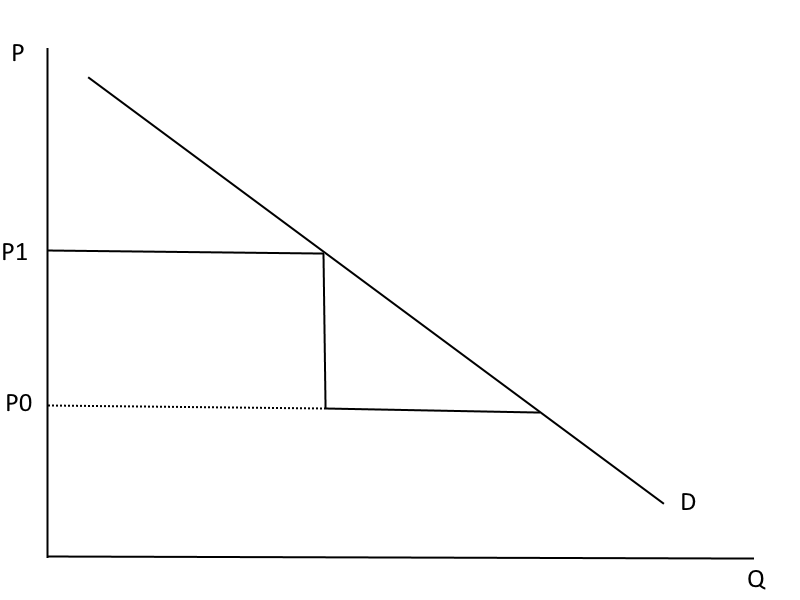

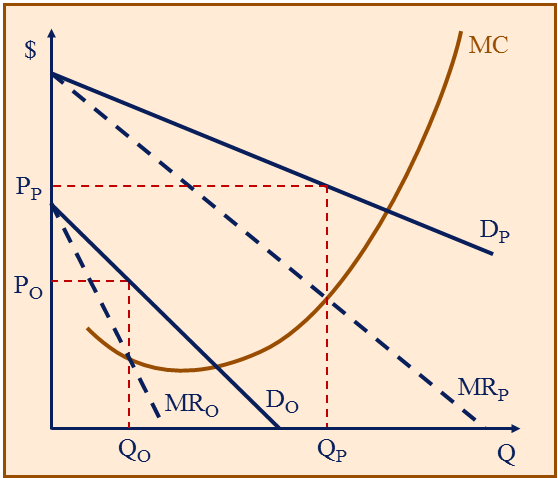

Imagine a monopolist can charge each consumer their willingness to pay. What would their marginal revenue be?

Price Discrimination

At what quantity would the monopolist choose to produce?

Is there deadweight loss?

Price Discrimination

A monopolist who charges only a single price produces deadweight loss... perfectly price discriminating monopolists do not produce DWL -- keep producing until marginal willingness to pay=marginal cost, i.e. the efficient (competitive) outcome

Price Discrimination

Where is consumer surplus?

Price Discrimination

Ginny’s Model Gas station is the only gas station in a small isolated town in Montana. She has estimated the monthly demand for gasoline in this town to be (where Q is in gallons):

Her total monthly cost is

And marginal cost is

A local market research firm comes to Ginny with a proposition. They tell her that if she contracts with them, they have a computer program that will analyze each customer that comes to her gas station, and can determine each customer’s willingness to pay for gasoline by the time they come to the cash register to pay. Assuming they could really do that and Ginny could then charge each customer his or her willingness to pay, what is the maximum monthly fee that Ginny should be willing to pay for these services? (Assume that the market demand is unaffected)

Price Discrimination

Second degree price discrimination (or block pricing/ "volume discounts"): used when each customer buys multiple units of a good.

The first X units cost more than the next X units.

Remember: it is only price discrimination if the discount is not cost justified

Price Discrimination

Captures some, but not all, of the consumer surplus. Some examples?

Why do firms do this instead of 1st degree?

Price Discrimination

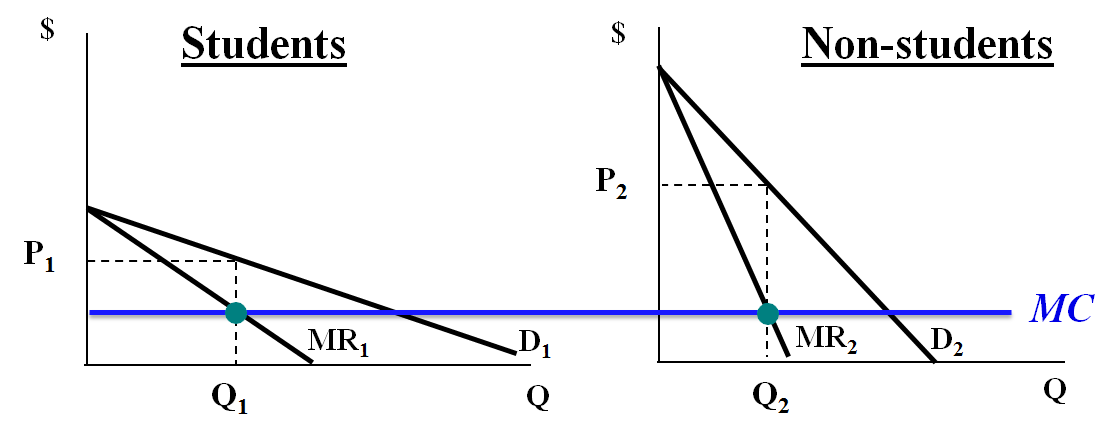

Third degree price discrimination ("market segmentation"):

Used when different groups of customers have different demands for the product.

Charge a different price in each segment:

- Vary prices to match customers’ willingness to pay

- Higher price charged to relatively less elastic segment (less price sensitive at current P and Q

Price Discrimination

Market segmentation:

Can be based on observables. Examples?

Or unobservables & self-selection. Examples?

Price Discrimination

Make marginal revenue equal across the two groups: students (more price-sensitive group) get lower price

Price Discrimination

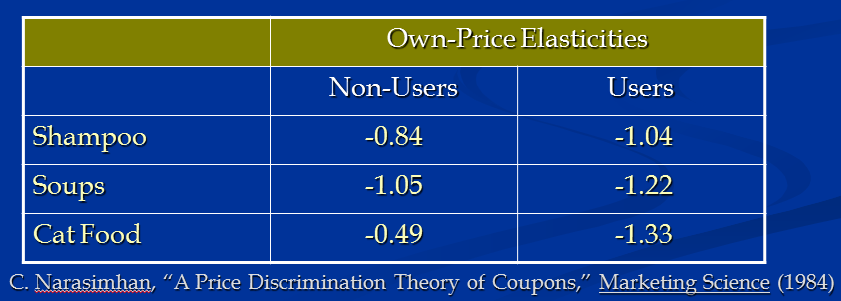

Coupons: some evidence?

Why use coupons/mail-in rebates? Why not simply discount the price (save costs of issuing and processing coupons)?

Coupons are a strategy to segment the market.

Users of coupons should have a more elastic demand.

Price Discrimination

Elasticities of coupon users vs. non-users

Price Discrimination

Inter-temporal Price Discrimination: Charge a high price early on, then drop the price later.

- Computer hardware, electronics

- Movie Premieres (big theatres initially; then 2nd run theaters)

- Books (hard covers first, then paperbacks)

- Sales (Filene’s Basement and automatic markdowns)

All of these strategies work by consumer self-selection

Price Discrimination

A pharmaceutical company sells drugs domestically and overseas. Although the world can be divided into a number of separate markets, for simplicity lets consider the U.S. and the “rest of the world” (RW). (Note: All values are expected present discounted

values.) Suppose that the demand for a drug in each of these markets is

here Q represents the number of daily doses (in millions) and P is the price per daily dose. Production costs are constant at $0.25 per daily dose. Given the information above, and assuming a monopoly pharmaceutical company, what would be the profit-maximizing quantity and price of a new successful drug in the U.S. and in the rest of the world (RW) if the two markets are separate? What would be the consumer surplus in the U.S. from such a drug? If the (fixed) development costs are 1.7 billion, what is the firm's (long term) profit?

Versioning

Price discrimination by versioning:

Offer a product line, and let consumers self-select based on convenience, ease of user interface, etc.

Needs based segmentation

Intuit sells several versions of Quicken, e.g., Starter for $29.99, Deluxe for $59.99, Premier for $89.99, Home & Business for $99.99

Versioning

Risk of cannibalization: Don’t make the low-end version too appealing, or it may attract some customers who otherwise would pay a premium for the high-end version.

e.g., IBM knew how to avoid this for home-office laser printers. Home version of IBM Laser Printer was a “value-subtracted” version. Home version printed 5 pages per minute versus business version, which printed 10 pages per minute.

(Carl Shapiro & Hal Varian, “Versioning: The Smart way to Sell Information, Harvard Business Review (Nov.-Dec. 1998), p. 112.

Versioning

Consider adding a premium option to the product line, even if it doesn’t sell well.

Experiment conducted with sales of microwave ovens:

Low-end Mid-range High-end

$109.99 $179.99 (45%)

$109.99 $179.99 (60%) $199.99

Consumers shy away from extremes. High-end product exists to push consumers to buy middle product.

(Carl Shapiro & Hal Varian, “Versioning: The Smart way to Sell Information, Harvard Business Review (Nov.-Dec. 1998), p. 112.

Price Discrimination

Some pitfalls of price discrimination:

Consumers may get "addicted" to coupons/discounts.

Could start a price war (e.g., if another company accepts your coupons).

Perception of price gouging/unfairness.

- Coke's "smart" vending machines (1999).

- Apple's $200 iPhone price drop in 2008

Price Discrimination

In a lot of ways, the Internet has made price discrimination both easier and harder.

Price Discrimination

"It was the same Swingline stapler, on the same Staples.com website. But for Kim Wamble, the price was $15.79, while the price on Trude Frizzell's screen, just a few miles away, was $14.29.

A key difference: where Staples seemed to think they were located.

A Wall Street Journal investigation found that the Staples Inc. website displays different prices to people after estimating their locations. More than that, Staples appeared to consider the person's distance from a rival brick-and-mortar store, either OfficeMax Inc. or Office Depot Inc. If rival stores were within 20 miles or so, Staples.com usually showed a discounted price."

Websites Vary Prices, Deals Based on Users' Information Wall Street Journal December 2012

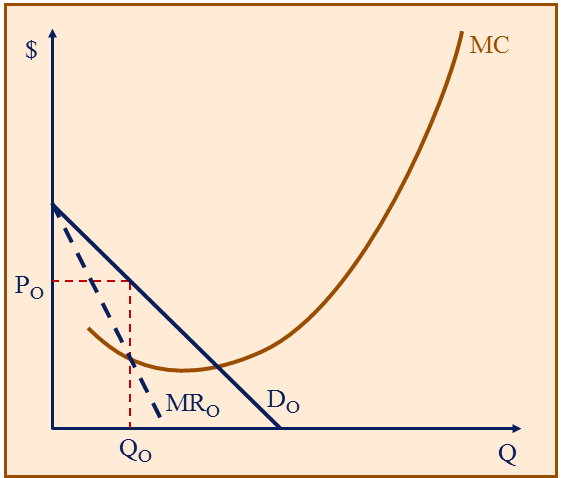

Peak Load Pricing

Peak-load pricing: Charging higher prices in high-demand periods than in low-demand periods because of differences in marginal cost (due to capacity constraints) at different output levels.

Business Practice: The intertemporal price differences we observe are often rooted in both peak-load and 3rd degree price discrimination (e.g., hotels, ski resorts, airlines … )

Peak Load Pricing

Low demand period

Peak Load Pricing

High demand period ("peak")

Peak Load Pricing

- Peak-load pricing is not price discrimination because price differences are cost based.

- Even firms in a competitive industry would want different peak and non-peak prices.

- Demand-based (price discrimination) and cost-based reasons for differential pricing are not mutually exclusive

Peak Load Pricing

Peak load pricing is NOT price discrimination: the prices vary because costs vary from peak to non-peak

- Peak-load pricing allows firms to operate more efficiently: they can serve their markets with a smaller installed base

- When firms don’t use high peak price, often have to have customers bear extra time cost (wait in line at restaurant, Disney) or face unavailability (full theater)

- Applies to non-firms too => Stockholm’s road infrastructure and pollution level

Peak Load Pricing

Peak load pricing or price discrimination?

How has Uber's surge policy worked out for them?

Two Part Pricing

Nespresso coffee machines & pods: “At 55 cents for a 4-g capsule, Nespresso coffee works out to a nerve-jangling $62 per lb….Nestlé doesn’t break out profits, but a former executive puts gross margins at about 85%...” (“Pod of Gold” Time.com, 7 Mar. 2011)

Examples of other products like this?

Two Part Pricing

Pricing for some products can be separated into two charges because the consumer has two decisions:

- whether to purchase the good or sign-up for the service; this is the entry fee (an up-front lump-sum fixed fee)

and

- how much of the good or service to buy (the intensity of use); this is the usage price or charge per additional unit … what we call “P”

Goal: Design a pricing strategy to capture as much consumer surplus as possible

Two Part Pricing

Trade-offs are:

- high entry fee reduces the number of customers

- charging mostly per unit which means you extract less CS per customer you get

Two Part Pricing

Illustrate concepts with a specific numerical example. Start with one type of consumers that are the same and progress to case where there are two market segments.

A typical individual has a demand curve for a product or service of:

P = 5 - 0.25Q.

Let P = price per unit (“usage price”), T = up-front fixed fee (“entry fee”), and Q = units purchased.

MC = 1; for simplicity, assume no fixed costs

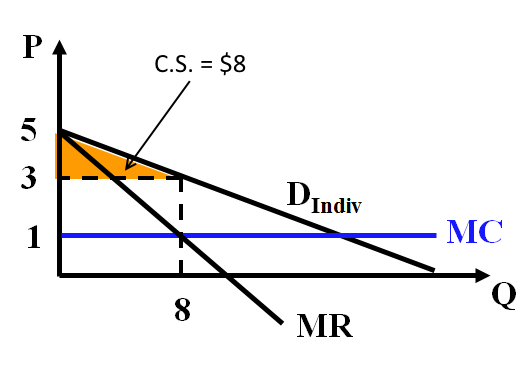

What is the “single-price” monopoly Q, P, and profits?

Two Part Pricing

MR = MC => 5 – 0.5Q = 1 => Q = 8

=> P = 5 – 0.25*8 => P = $3

=> Profit = 3(8) – 1(8) = $16

Two Part Pricing

The firm can do better with a per unit price of $3 by charging a fixed fee. How much should the fee be? What is profit?

But wait--the firm can do even better, right?

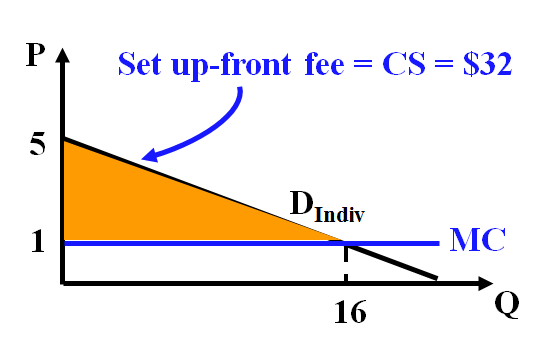

Two Part Pricing

P = MC = 1 => 1 = 5 – 0.25Q => Q = 16

CS = 0.5(16)(5 – 1) = $32

Profit = (1*16 + 32) – (1*16) = $32

Two Part Pricing

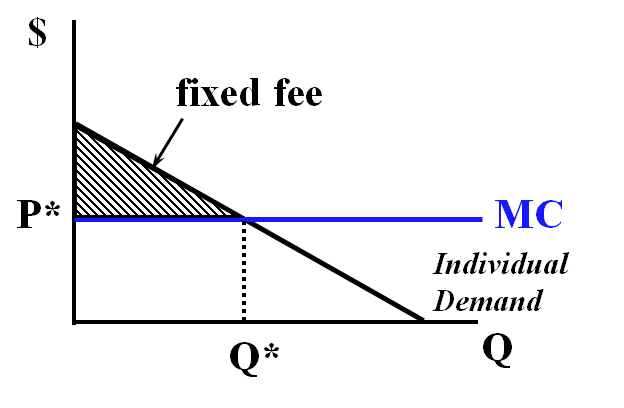

In general--set P=MC, fixed fee (T)=CS.

Note the disappearance of the MR line!

Two Part Pricing

For a single customer type:

- Set P = MC; set T (fixed fee)= CS at P = MC

But there may be more than one type of customer.

- Sometimes you can identify different customer types of observables (student vs. non-student)

- But sometimes you can't or preventing arbitrage is impossible

Two Part Pricing

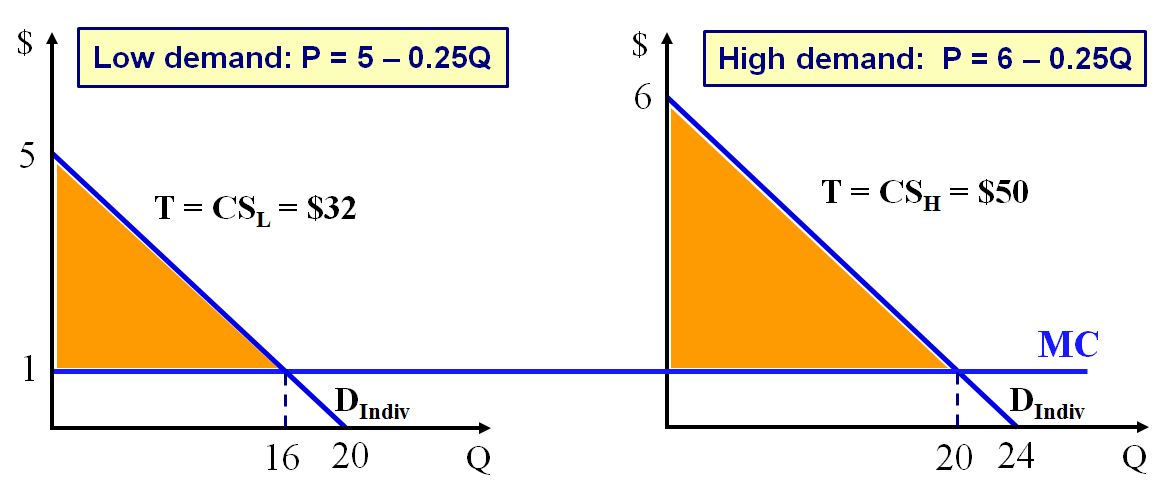

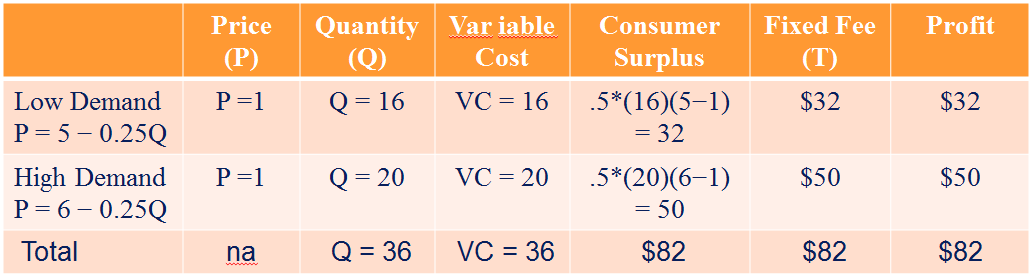

Now assume two types of customers, with demand given by

P = 5 – 0.25Q for “low demand” consumers

P = 6 – 0.25Q for “high demand” consumers

Assume MC = 1, and no fixed costs (for simplicity)

Firm can identify who is low demand and who is high demand; could charge a different (T, P) combo to each group.

- Low demand group: what is optimal TL and PL ?

- High demand group: what is optimal TH and PH ?

- What is total profit?

Two Part Pricing

When types can be identified and firm can offer a completely different two part tariff (T and P) to each type, then one can consider the two types as being 2 completely separate markets.

Hence, same logic from the “Single Consumer Type” case applies (for each market) and the optimal pricing strategy is:

- PL = MC = 1, TL = CSL at PL = 1

- PH = MC = 1, TH = CSH at PH = 1

- Profit=?

Two Part Pricing

Firm’s Profit = TR–TC = [(1*16)+(1*20)+32+50] – [(1*16)+(1*20)] = $82

Two Part Pricing

Firm’s Profit = TR–TC = [(1*16)+(1*20)+32+50] – [(1*16)+(1*20)] = $82

Would this work for an amusement park (Fixed fee=entrance, per unit=rides)?

What about a Nespresso machine (Fixed Fee=Machine, Per Unit=Pods)?

Two Part Pricing

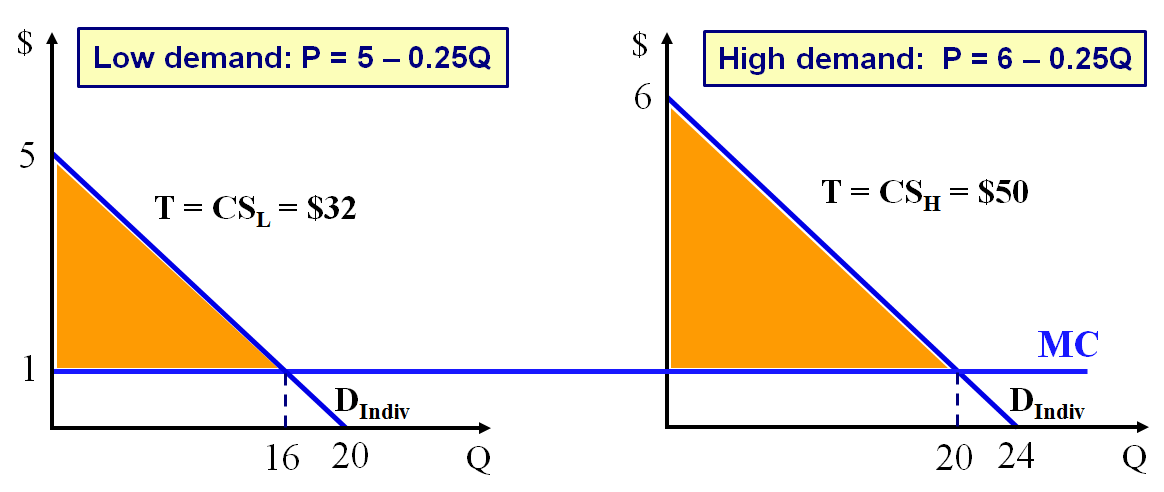

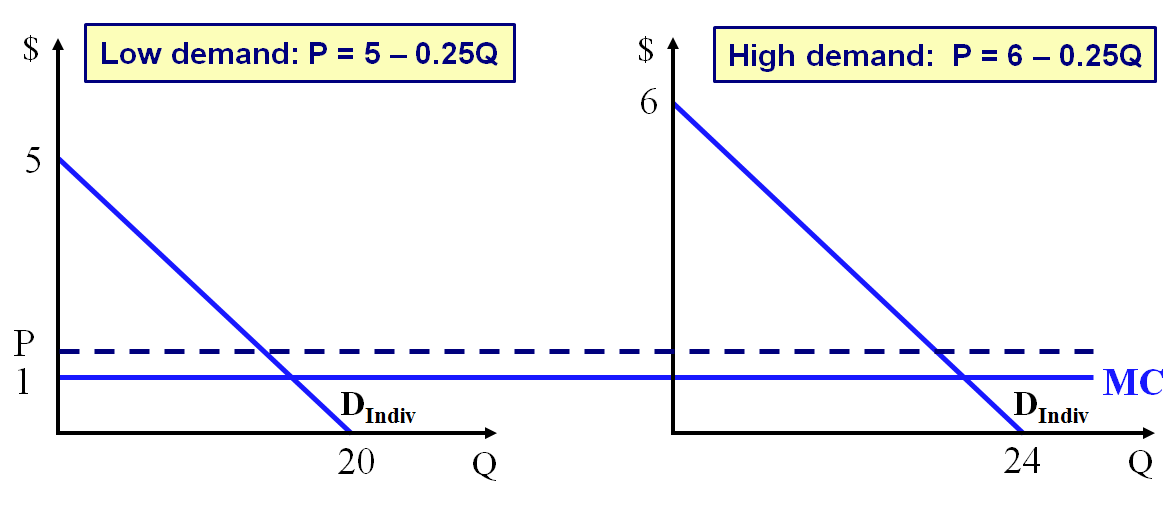

Now, let's assume the firm either cannot identify who is the high type and who is the low type or preventing arbitrage is impossible.

As a result, the firm must charge the same price P and entry fee T to both. MC = 1 (no fixed costs, as before).

•P = 5 − 0.25Q for “low demand” consumers, and

•P = 6 − 0.25Q for “high demand” consumers

Two Part Pricing

Suppose set P = MC = 1: What is the optimal fixed fee?

What is profit?

Two Part Pricing

Let's say we increase P a little bit. Would we do better or worse?

Two Part Pricing

Let's try it: Let P = $1.50 and see what happens to profits.

Same setup for demand and costs

T = ? ; Profits = ?

Remember:

Demand (Low): P=5-0.25Q

Demand(High): P=6-0.25Q

Two Part Pricing

By trial and error (or calculus) you can show that profits will go up if you increase the per unit price P to above MC (here optimal to set P=1.5) and then charge FF equal to the “remaining” CS of the low-demand type to both.

This is called (colloquially) the razor - razor blade pricing strategy: Lower the fixed fee, mark up the price per unit

Two Part Pricing

What is the intuition?

The higher per unit price P allows you to capture some of the consumer surplus of the high-demand type when you cannot do it by charging those customers their own (higher) fixed fee

Two Part Pricing

If customers have very similar demands, charge P=MC and set entry fee at CS.

If demand by the two types are different but not too different, then charge P > MC and set fixed fee T= consumer surplus for low-demand type

Two Part Pricing

If demands are very different, then “abandon” the low demand group. i.e., charge P = MC and set FF = CS for the high demand group.

E.g. if demand of high types was equal to P = 7 - 0.25Q instead of P = 6 - 0.25Q, you would want to ignore the low demand consumers and set T= CS from the high demand type

Two Part Pricing

Strategy: Make a small initial profit on the razor, but big profits over time on the many razor blades that people buy

Note: Here most of the profit comes from the per unit price!

- Xerox used to do this by insisting that customers also buy copy paper from Xerox.

- e-Readers and eBooks.

- Nespresso and nespresso pods.

- Other examples

Two Part Pricing

Possible problems:

IOMEGA’s Drives and Disks: used razor-razor blade pricing

- Customers did not need many disks

- Disks were re-usable

- Not good type of product to do this with

Two Part Pricing

Possible problems:

If other companies can make the "razor," they may undercut you. Remember, you are pricing it above your costs--makes it attractive for other firms to enter!

Lecture 21

By umich

Lecture 21

- 732