@inline and @specialized

What Do They Do?

Should I Be Using Them?

Chris Birchall

Scala Days Berlin 2016

Agenda

-

Inlining

- In general

- On the JVM

- In Scala

- Benchmarks

-

Speciali{s|z}ation

- JVM types and generics in Java and Scala

- Specialisation in Scala

- Benchmarks

WARNING

Bytecode

ahead!

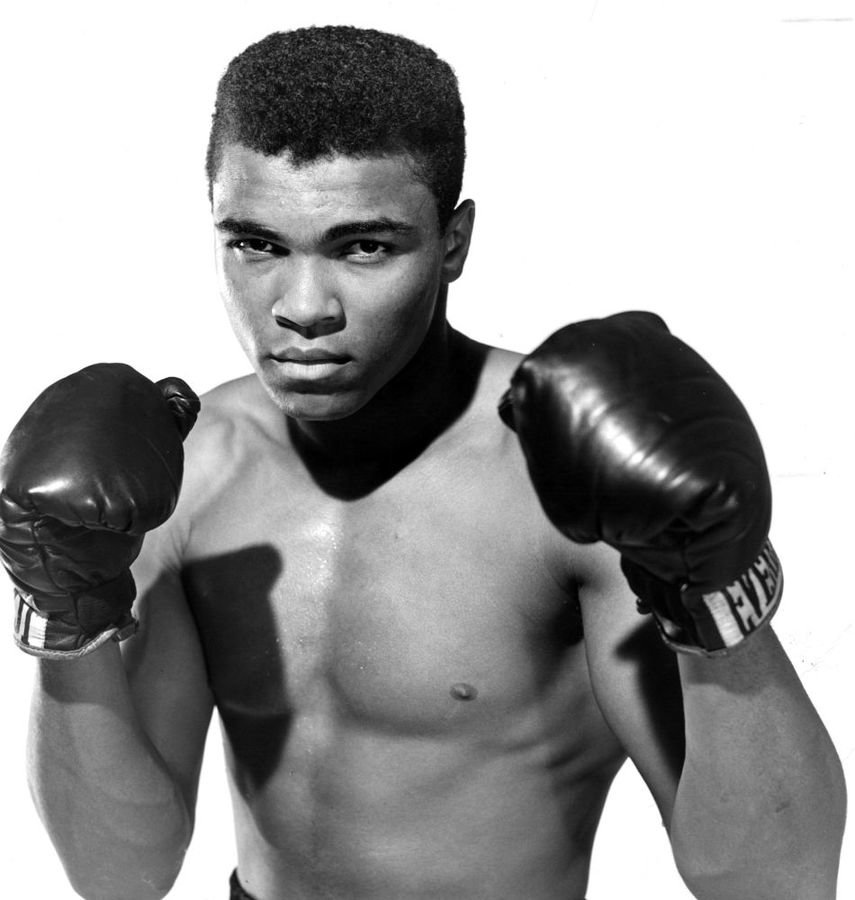

me me me

-

Chris Birchall

-

@cbirchall

-

github.com/cb372

Why should I care?

Performance matters!

(sometimes)

Inlining

Inlining

Remove a function call

by copying the function body into the caller

def target(a: Int, b: Int) = {

(a + b) * 2

}

def caller = {

val x = 1

val y = 2

target(x, y)

}def caller = {

val x = 1

val y = 2

(x + y) * 2

}inlining

Inlining

- Not specific to Scala or JVM

- Removes overhead of function call

- Enables further optimisations

Removes function call overhead

def target(a: Int, b: Int) = {

(a + b) * 2

}

def caller = {

val x = 1

val y = 2

target(x, y)

}def caller = {

val x = 1

val y = 2

(x + y) * 2

}inlining

// def target

0: iload_1

1: iload_2

2: iadd

3: iconst_2

4: imul

5: ireturn

// def caller

0: aload_0

1: iconst_1

2: iconst_2

3: invokevirtual #24

6: ireturn0: iconst_1

1: iconst_2

2: iadd

3: iconst_2

4: imul

5: ireturnIf the resolved method is not signature polymorphic (§2.9), then the invokevirtual instruction proceeds as follows.

Let C be the class of objectref. The actual method to be invoked is selected by the following lookup procedure:

-

If C contains a declaration for an instance method m that overrides (§5.4.5) the resolved method, then m is the method to be invoked, and the lookup procedure terminates.

-

Otherwise, if C has a superclass, this same lookup procedure is performed recursively using the direct superclass of C; the method to be invoked is the result of the recursive invocation of this lookup procedure.

-

Otherwise, an AbstractMethodError is raised.

The objectref must be followed on the operand stack by nargs argument values, where the number, type, and order of the values must be consistent with the descriptor of the selected instance method.

If the method is synchronized, the monitor associated with objectref is entered or reentered as if by execution of a monitorenter instruction (§monitorenter) in the current thread.

If the method is not native, the nargs argument values and objectref are popped from the operand stack. A new frame is created on the Java Virtual Machine stack for the method being invoked. The objectref and the argument values are consecutively made the values of local variables of the new frame, with objectref in local variable 0, arg1 in local variable 1 (or, if arg1 is of type long or double, in local variables 1 and 2), and so on. Any argument value that is of a floating-point type undergoes value set conversion (§2.8.3) prior to being stored in a local variable. The new frame is then made current, and the Java Virtual Machine pc is set to the opcode of the first instruction of the method to be invoked. Execution continues with the first instruction of the method.

invokevirtual

Enables further optimisations

class A(x: Int) {

def plusOne() = x + 1

}

def two: Int = {

val a = new A(1)

a.plusOne()

}def two: Int = {

val a = new A(1)

a.x + 1

}def two: Int = {

1 + 1

}

escape

analysis

inlining

Conclusion:

Inlining is a Good Thing.

So...

Why not inline everything?

Answer: Code is data

- Inlining duplicates code -> code gets bigger

- If it gets too big, doesn't fit in CPU caches

So we should only inline HOT functions

The JVM

(specifically HotSpot)

is pretty good at this

Inlining in HotSpot

Conditions for inlining

-

Small

-

-XX:InlineSmallCode (default 1000 bytes of assembly)

-

-XX:MaxInlineSize (default 35 bytes of bytecode)

-

-XX:MaxTrivialSize (default 6 bytes of bytecode)

-

-

Hot

-

-XX:MinInliningThreshold (default 250 invocations?)

-

-

Caller not already too big (default 325 bytes of bytecode)

-

Not a native method

-

...

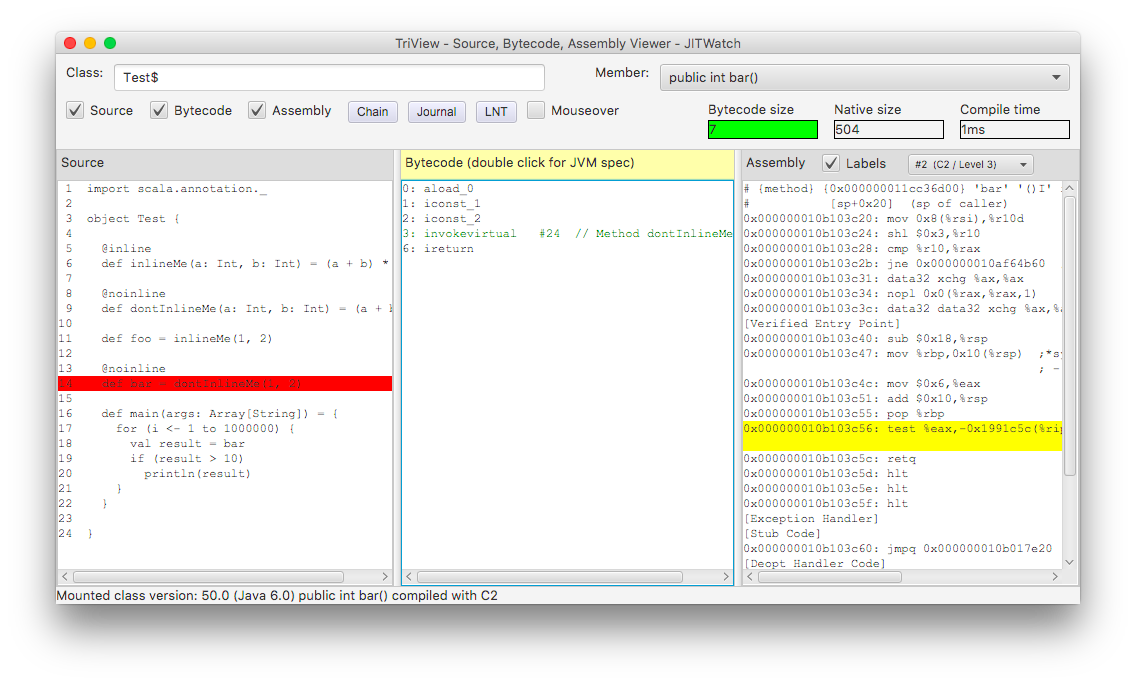

JITWatch

Inlining in Scala

import scala.annotation._

object Test {

@inline

def inlineMe(a: Int, b: Int) = (a + b) * 2

@noinline

def dontInlineMe(a: Int, b: Int) = (a + b) * 2

def foo = inlineMe(1, 2)

def bar = dontInlineMe(1, 2)

}$ scalac -optimise -Yinline-warnings Test.scalaInlining heuristics

(Scala 2.10.0 - 2.11.x)

- Only inline "effectively final" methods

- For external libs:

- In general, only @inline-annotated methods

- Special treatment for scala.runtime.*, scala.Predef

- Special treatment for 'monadic' methods, higher-order funcs

-

Score-based heuristics

- it’s bad to make the caller larger if it was small

- it’s bad to inline large methods

- it’s good to inline higher order functions

- it’s good to inline closures

New optimiser in 2.12

only inline @inline-marked methods,

and always inline them,

including under separate-compilation

-

Also inline higher-order functions

-

No more score-based heuristics

-

Better synergy with HotSpot

Inlining HOFs

def foo() = {

for (i <- 1 until 10) {

println(i)

}

}def foo() = {

val range = new Range(1, 10, 1)

val f = new $anonfun$foo$1() // println(i)

range.foreach(f)

}desugar

Inlining HOFs

def foo() = {

val range = new Range(1, 10, 1)

val f = new $anonfun$foo$1()

if (!range.isEmpty) {

var i = range.start

while (true) {

f.apply(i)

if (i == range.lastElement) return

i += range.step

}

}

}inline

Range.foreach

Inlining HOFs

def foo() = {

val range = new Range(1, 10, 1)

val f = new $anonfun$foo$1()

if (!range.isEmpty) {

var i = range.start

while (true) {

println(i)

if (i == range.lastElement) return

i += range.step

}

}

}inline

closure

Inlining HOFs

def foo() = {

val range = new Range(1, 10, 1)

val f = new $anonfun$foo$1()

if (!range.isEmpty) {

var i = range.start

while (true) {

println(i)

if (i == range.lastElement) return

i += range.step

}

}

}eliminate

dead code

Let's benchmark!

WARNING

Like most benchmarks,

this one is probably wrong

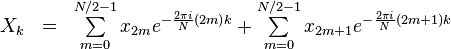

Fast Fourier Transform

Cooley-Turkey algorithm

- Recursive

- Lots of numerical ops on complex numbers

final case class Complex(r: Double, i: Double) {

@inline def +(x: Complex) = Complex(r + x.r, i + x.i)

@inline def -(x: Complex) = Complex(r - x.r, i - x.i)

@inline def *(x: Complex) = Complex(r * x.r - i * x.i, ...)

}Benchmark results

| HotSpot inlining disabled | HotSpot inlining enabled | |

|---|---|---|

| @inline | 1208 ± 11 | 360 ± 10 |

| @noinline | 1226 ± 14 | 355 ± 4 |

Scala 2.11.8, GenASM

| HotSpot inlining disabled | HotSpot inlining enabled | |

|---|---|---|

| @inline | 1237 ± 12 | 330 ± 4 |

| @noinline | 1243 ± 13 | 329 ± 4 |

Scala 2.12.0-M4

- Units = ms/op, smaller is better

- FFT of 64k random doubles

JMH settings: 20 warmup, 20 iterations, 10 forks

Further reading

-

Oracle slides about HotSpot optimisations, including inlining

-

Blogposts about Java performance tuning

-

Explanation of initial prototype of the new optimizer in Scala 2.12

- Explanation of Fourier transform

Specialisation

Types in the JVM

-

Primitive types

- boolean, byte, char, short, int, long, float, double

- Memory-efficient (no object header overhead)

- Passed by value

-

Reference types

- Anything that extends from java.lang.Object

- Passed by reference

- (pedantry: actually a reference is passed by value)

Generic methods in Java

public class Generic {

<A> void foo(A a) {

return;

}

void test() {

foo("hello");

foo(123);

}

}Generic methods in Java

<A> void foo(A);

descriptor: (Ljava/lang/Object;)V

Code:

0: return

void test();

descriptor: ()V

Code:

0: aload_0

1: ldc #2 // String hello

3: invokevirtual #3 // Method foo:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

6: aload_0

7: bipush 123

// Method java/lang/Integer.valueOf:(I)Ljava/lang/Integer;

9: invokestatic #4

12: invokevirtual #3 // Method foo:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

15: return

Scala types

Any

AnyVal

Int

Double

...

AnyRef

j.l.Object

}

JVM primitives

Generic methods in Scala

import scala.collection.mutable

object StdlibMapExample {

def foo(): Unit = {

val map = mutable.Map.empty[String, Int]

map.put("key", 123)

}

}Generic methods in Scala

public void foo();

Code:

0: getstatic #18 // Field scala/collection/mutable/Map$.MODULE$:Lscala/collection/mutable/Map$;

3: invokevirtual #22 // Method scala/collection/mutable/Map$.empty:()Lscala/collection/mutable/Map;

6: astore_1

7: aload_1

8: ldc #24 // String key

10: bipush 123

// Method scala/runtime/BoxesRunTime.boxToInteger:(I)Ljava/lang/Integer;

12: invokestatic #30

15: invokeinterface #36, 3 // InterfaceMethod scala/collection/mutable/Map.put:(Ljava/lang/Object;Ljava/lang/Object;)Lscala/Option;

20: pop

21: return

Specialisation

Generate multiple versions of a class

to remove boxing overhead

Specialisation

MySpecialMap$mcB$sp.class // byte

MySpecialMap$mcC$sp.class // char

MySpecialMap$mcD$sp.class // double

MySpecialMap$mcF$sp.class // float

MySpecialMap$mcI$sp.class // int

MySpecialMap$mcJ$sp.class // long

MySpecialMap$mcS$sp.class // short

MySpecialMap$mcV$sp.class // null

MySpecialMap$mcZ$sp.class // boolean

MySpecialMap.class // AnyRefclass MySpecialMap[@specialized A] {

def put(key: String, value: A): Unit = ...

def get(key: String): Option[A] = ...

}

Specialisation

class MySpecialMap[@specialized A] {

def put(key: String, value: A): Unit = {}

def get(key: String): Option[A] = None

}

object Test {

def foo(): Unit = {

val map1 = new MySpecialMap[Int]

map1.put("key", 123)

}

}Specialisation

0: new #15 // class MySpecialMap$mcI$sp

3: dup

4: invokespecial #16 // Method MySpecialMap$mcI$sp."<init>":()V

7: astore_1

8: aload_1

9: ldc #18 // String key

11: bipush 123

// Method MySpecialMap.put$mcI$sp:(Ljava/lang/String;I)V

13: invokevirtual #24

16: return

How does the caller know?

Constant pool:

...

#7 = Utf8 Lscala/reflect/ScalaSignature;

#8 = Utf8 bytes

#9 = Utf8 ??e2A!??? \taQ*_*qK?L?\r\'ba*\t1!A?=K6?H/

??U?a?F\n?? ?\"?C???%Q?AC??g? G.Y???%?a!?8z%?4?\"???\t?y?A?

j]&$h?F??!\r\t?AE???A?1????\t%)??)A?? ?aCA?B#\t9\"???\t1%??$

??? >$?.?8h!\tA1$?? ?\t??I\=)?Qq?C?? ?\t??BA?ta? ?.?7ju?$?\"

???\t???a?9viR?Ae\n???!)?B??\n??)f.?;\t !\n??A???-,????+[9??

bK??Y%\ta??:fI?4?B??0???FO]5oO*?A&???c??\rAE??m?dW/???g?!\t?

N??O?$HCA?9!\rAaGE??o%?aa?9uS>t?\"??3??I?@specialized is a static annotation

→ stored in the class's ScalaSignature

^^^ somewhere in there! ^^^

Space tradeoff

-

Specialisation generates a lot of duplicated code

-

But you can specify the types you want to specialise

class MySpecialMap[@specialized (Int, Long, Double) A] {

...

}

Boxing in the Scala stdlib

(as of 2.11.8)

-

Tuple1: @specialized(Int, Long, Double)

-

Tuple2: @specialized(Int, Long, Double, Char, Boolean)

-

Tuple3+: BOXING!

-

Option: BOXING!

-

Function{0,1,2}: Various combinations of @specialized

-

Immutable collections: BOXING!

-

Mutable collections: BOXING!

Alternatives

Let's benchmark!

Bloom filter

class BloomFilter[@specialized(Int) A](m: Int, k: Int)

(implicit hashFunctions: HashFunctions[A]) {

def add(value: A): Unit = ...

def query(value: A): Boolean = ...

}

trait HashFunctions[@specialized(Int) A] {

def alpha(value: A): Int

def beta(value: A): Int

}

Benchmark results

- Insert 42

- Query for membership of 123

| Average time taken | |

|---|---|

| With specialisation | 0.163 ± 0.001 |

| Without specialisation | 0.165 ± 0.001 |

JMH settings: 20 warmup, 20 iterations, 10 forks

Units = μs/op, smaller is better

Mutable buffer

class Buffer[@specialized(Int) A](initialCapacity: Int) {

def append(value: A): Unit = ...

def foreach(f: A => Unit): Unit = ...

}

Benchmark results

Call foreach on a buffer containing 1 million Ints

| Average time taken | |

|---|---|

| With specialisation | 4539 ± 67 |

| Without specialisation | 9168 ± 86 |

JMH settings: 20 warmup, 20 iterations, 10 forks

Units = μs/op, smaller is better

Further reading

Honourable mentions

Honourable mentions

- @strictfp

- Adds strictfp (strict floating point) flag to classfile

- @switch

- Ensures a pattern match generates performant bytecode (either tableswitch or lookupswitch)

-

@elidable

An annotation for methods whose bodies may be excluded from compiler-generated bytecode

Summary

@inline

@specialized

Thank you!

@inline and @specialized - Scala Days Berlin 2016

By Chris Birchall

@inline and @specialized - Scala Days Berlin 2016

- 3,941