Javier García-Bernardo

offshore financial centers and inequality

wealth Inequality is rising

Check this: https://mkorostoff.github.io/1-pixel-wealth/

2020

2021

2020

2021

~g

~r

rental income

dividends

capital gains

interest

r > g

growth rate

rate of return of capital

Long-term dynamics

Dawid

Javier

Source data: 2016 Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances

Source: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/chart-assets-make-wealth/

Source: World Inequality Database

Wealthy people have access to better investments and lower taxation

A closer look at r

How to control inequality in an era of low-growth?

Option 1: Progressive tax on personal income

However... it does not affect r,

often the major driver

of inequality

However... we have been

reducing the progressiveness

of personal income tax

Option 2: Tax returns of capital to reduce r

Tax at the individual level:

- Tax dividend, interest and rental income

- Tax capital gains

Tax at corporate level:

- Tax corporate income

However...

- we have been reducing these taxes

How to control inequality in an era of low-growth?

Option 3: Tax wealth directly

How to control inequality in an era of low-growth?

offshore financial centers

Corporations: Move financial assets to OFCs (semi-legal)

+5€ (coffee)

-1€ (brand)

-4€ (costs)

Starbucks Spain

Starbucks NL

EBT: 0€

EBT: 1€

+1€ (brand)

+5€ (coffee)

-4€ (costs)

Cafe Pepe

EBT: 1€

Tax: 0€

Profit: 0€

Tax: 0.07€

Profit: 0.93€

Tax: 0.25€

Profit: 0.75€

Location of profits

Location of employees

the Netherlands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Ireland and Singapore

Individuals create companies offshore and:

- Invest from there to avoid capital gains, dividend, interest or rent taxes until the profits are repatriated (mostly legal)

- Hide assets there (mostly illegal)

- Avoid inheritance tax by hiring a life insurance inside a trust

... lost of other dubious tax schemes involving shell companies offshore

OFCs “process” around $6 000 000 000 000 yearly.

offshore financial centers

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/06/opinion/income-tax-rate-wealthy.html

OFFSHORE FINANCIAL CENTERS

- So, which countries are OFCs?

- Definitions differ

- Highly contested and politicized

- Two approaches:

- Misalignment approaches (e.g. ratio FDI/GDP)

- Assumes all countries are the same

- Regulatory framework (e.g. tax haven)

- Does not measure the importance of countries

- Misalignment approaches (e.g. ratio FDI/GDP)

Solution: Network science!

Data: Orbis

- 71,201,304 ownership links between firms

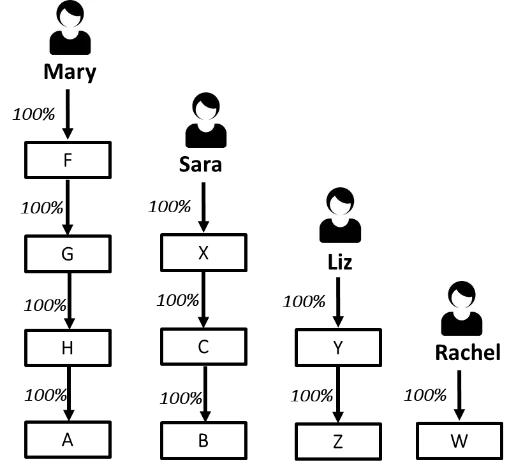

Step 1: Construct global ownership chains, representing money flows

- Start from each company, find the owners recursively

- Weight the chain by the revenue of the first chain

- Take the ownership into consideration

Method:

We look at which countries are used disproportionately in transnational ownership chains.

Step 2: Sink OFC

Countries that attract and retain capital. They are situated disproportionately at the end of the chains (where the owners are)

Step 3: Conduit OFC

Countries that are attractive intermediate destinations because their numerous tax treaties, low or zero withholding taxes, strong legal systems and good reputations for enabling the quiet transfer of capital without taxation. In the middle of ownership chains.

Adding the ownership chains entering and country, subtracting the ones leaving the country

Summing the ownership chains going from a sink, into the country analyzed, and out to a third country

Step 1:

weighted by the revenue of Franziskaner

|Source - Sink|

Measures total importance

Step 2: sink OFFshore financial centers

Green: Source>Sink

Yellow: Sink>Source

|Source - Sink|/GDP

Measures relative importance

High relative and total importance

High total importance, low relative importance

Low total importance, high relative importance

15 companies per capita

Step 2: sink OFFshore financial centers

Step 3: conduit OFFshore financial centers

Value(Sink→Country→Third country)/GDP

Value(Third country→Country→Sink)/GDP

Five countries channel 47% of corporate offshore investment from tax havens:

Netherlands (23%), the UK (14%), Switzerland (6%), Singapore (2%) and Ireland (1%).

Not all OFCS are equal

why The netherlands?

Historical reasons:

- Curaçao: Just before World War II, Dutch multinationals moved to CW to avoid the confiscation of assets.

- Curaçao developed a prominent and flexible management industry.

- Used to avoid withholding taxes (no longer applicable)

- Effective tax rate in CW: 2.4 - 3%

During the 80s there was a push towards attracting corporations in the Netherlands.

importance of the netherlands

Reasons

- Logistic:

- Located in the heart of Europe.

- Outstanding infrastructure.

- Highly educated and multilingual workforce.

- Well-developed trust and management services.

- Beneficial tax regime:

- No withholding taxes for interest and royalties.

- No real withholding tax for dividends.

- Patent box

- Lenient anti tax avoidance legislation

- Low transparency

- Advance Tax Rulings (ATR) and Advance Pricing Agreements (APA)

- Investor protection

- Large number of bilateral investment treaties

- Advanced tax ruling system (increases certainty)

The Netherlands is extremely successful at attracting holding companies (assets ~8 times GDP), mainly to avoid taxes.

Tax revenue collected:

- 8 billion / year

Tax revenue lost by other countries:

- 36 billion / year

Employment:

- 3000 of business service professionals

- Some other thousands by headquarters and shared service centers

summary

- Within-country wealth inequality is rising

- Offshore financial centers contribute to this process by allowing corporations and individuals to avoid taxes.

- Defining offshore financial centers is difficult and politiziced

- Corporate ownership networks contain rich information on how corporations organize

- We find that OFCs come in two flavors: conduits and sinks

- Conduits are highly developed countries with strong regulatory environments, not exotic far-flung islands.

- Offshore financial centers contribute to other types of inequalities:

- Within states

- Between capital and states

javier.garcia.bernardo@gmail.com

Copy of PPLE

By Javier GB

Copy of PPLE

sink and conduits in Corporate Structures

- 797