Citizen Candidate Model

Lecture 2, Political Economics I

OSIPP, Osaka University

13 October, 2017

Masa Kudamatsu

Did you come up with

a research question

for your term paper?

If yes, is your research question

original, interesting, and feasible?

Motivations for today

Does the Median Voter Theorem still hold

if candidates cannot commit to their electoral platform?

cf. Lecture 1

Osborne and Slivinski (1996) and Besley and Coate (1997)

develop a theoretical framework

now widely known as the citizen-candidate model

Basic Model

We follow Section 5.3 of Persson and Tabellini (2000)

Players

A continuum of citizens, each indexed by

NOTE: The model endogenously derives who becomes a candidate

Citizens' actions (Timing of Events)

1

2

3

Each citizen decides whether to become a candidate

Each citizen decides which candidate to vote for

Entry into politics

Election

Inauguration of a new government

The candidate winning the majority of votes selects a policy

If no one becomes a candidate,

the default policy will be implemented

Citizen i's Preference

For the ease of comparison to the Downsian model

we assume a single-peaked preference (cf. Lecture 1)

Citizen i's payoff function as one-dimensional policy

Denote i's ideal policy by

Citizen i's Preference (cont.)

Becoming a candidate incurs a cost of

Electoral campaign expenditure

Opportunity cost (i.e. private sector wage)

Analysis

Equilibrium concept

The model is a dynamic game with complete information

Use the Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium as the solution concept.

Thus, we proceed with backward induction

Backward induction

1

2

3

Each citizen decides whether to become a candidate

Each citizen decides which candidate to vote for

Entry into politics

Election

Inauguration of a new government

The candidate winning the majority of votes selects a policy

If no one becomes a candidate,

the default policy will be implemented

Winning candidate's optimization

Denote the winning candidate by

She solves

So she chooses her own ideal policy

Even if we allow candidates to propose a policy before election

Winning candidate's optimization (cont.)

Choose her own ideal policy

no citizen believes it to be chosen once they are elected

Backward induction

1

2

3

Each citizen decides whether to become a candidate

Each citizen decides which candidate to vote for

Entry into politics

Election

Inauguration of a new government

The candidate winning the majority of votes selects a policy

If no one becomes a candidate,

the default policy will be implemented

Optimization by citizens as voters

Single-peaked preference

Vote for the candidate whose ideal policy is the closest to their own

If there are at most two candidates...

Winning candidate:

the one preferred by the median voter (cf. Lecture 1)

We focus on this case: see Propositions 8 and 9 of Besley and Coate (1997) for the possibility of three-candidate equilibria

Optimization by citizens as voters (cont.)

We skip the case where there are three or more candidates

Propositions 8 and 9 of Besley and Coate (1997) show

non-existence of three-candidate equilibrium

under mild additional assumptions

Backward induction

1

2

3

Each citizen decides whether to become a candidate

Each citizen decides which candidate to vote for

Entry into politics

Election

Inauguration of a new government

The candidate winning the majority of votes selects a policy

If no one becomes a candidate,

the default policy will be implemented

Equilibrium conditions for entry into politics

1

Those running for office prefer to do so given that the other candidate is running

2

No other citizen wants to run for office

One-candidate equilibrium

Suppose a median citizen becomes a sole candidate

Does the median citizen get better-off by running for office?

Yes, as long as

Plausible if the default policy is a government shutdown

One-candidate equilibrium

Suppose a median citizen becomes a sole candidate

Do other citizens prefer becoming a candidate as well?

No. Other citizens cannot win the election against the median citizen

Other median citizens won't become a candidate because

The policy will be the median citizen's ideal one anyway

Becoming a candidate is costly

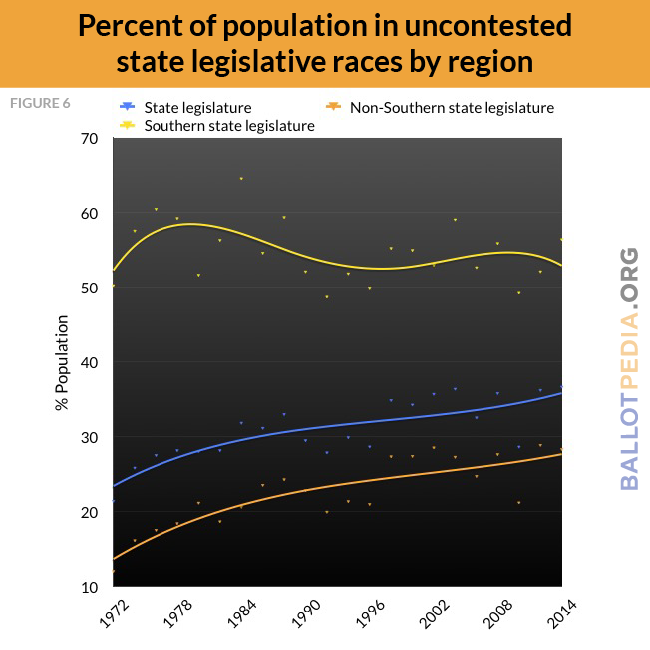

Uncontested elections in reality

Some constituencies for US state legislature, especially in the South

Source: Ballotpedia.org

So far, the model prediction is the same as the Median Voter Theorem

But the citizen-candidate model has other equilibria with policy divergence

Two-candidate equilibria

L prefers running for office if

Suppose two citizens, , run for office

denote the probability that L wins the election against R

R prefers running for office if

Let

Two-candidate equilibria (cont.)

Rearranging the terms yields:

Suppose two citizens, , run for office

where

is the probability that L wins the election against R

Two-candidate equilibria (cont.)

For these two conditions to hold,

Two-candidate equilibria (cont.)

For to be the case

the median citizen should be indifferent between L and R

Then we have

Summarizing so far, citizens R and L run for office if

Two-candidate equilibria (cont.)

Median citizens are indifference: so each wins with prob. 1/2

Citizen L prefers running for office to letting R win

Citizen R prefers running for office to letting L win

1

2

3

Why not the third citizen runs for office?

Even if it's the median citizen who runs as the third candidate...

No citizens with change their vote for the median

Otherwise, their favorite candidate will lose for sure

The same is true for those with

The median citizen cannot win: she won't run

Strategic voting vs sincere voting

With three candidates

voters no longer vote for the policy closest to their ideal

We call such voting behavior as "strategic voting"

as oppose to "sincere voting" (vote for the policy closest to ideal)

Osborne and Slivinski (1996) propose the sincere voting version of the citizen candidate model

Strategic voting vs sincere voting (cont.)

Empirically, difficult to tell whether voters are strategic or sincere

Strategic voting may imply voting in a sincere way

Using structural estimation, Kawai and Watanabe (2013 AER) show:

63-85% of voters are strategic in Japanese general elections

while only 1-4% vote in a non-sincere way

With strategic voting, the following three conditions are sufficient

Two-candidate equilibria (cont.)

Median citizens are indifference: so each wins with prob. 1/2

Citizen L prefers running for office to letting R win

Citizen R prefers running for office to letting L win

1

2

3

Multiplicity of two-candidate equilibria

Median citizens are indifference: so each wins with prob. 1/2

Citizen L prefers running for office to letting R win

Citizen R prefers running for office to letting L win

1

2

3

Many pairs of citizens L and R satisfy the condition #1

Multiple two-candidate equilibria

Median citizens are indifference: so each wins with prob. 1/2

Citizen L prefers running for office to letting R win

Citizen R prefers running for office to letting L win

1

2

3

Among such pairs satisfying the condition 1...

the distance between L and R's bliss point must be large enough

Implications

Policy divergence as an equilibrium

The Downsian model can only explain policy convergence

The citizen-candidate model can also explain policy divergence

even a very large one under strategic voting

Multiple Equilibria

The citizen-candidate model doesn't yield a unique prediction

So the model cannot be tested empirically

in terms of policy outcomes

Evidence

Testing the citizen-candidate model

We cannot test the model's predictions due to multiple equilibria

But we can test the model's no-commitment assumption

Otherwise there is no reason to believe in the model

rather than in the Median Voter Theorem

Very influential paper in two senses

Provide evidence against the Downsian model and in favor of the citizen-candidate model

Pioneer regression discontinuity design in economics

(along with Pettersson-Lidbom 2008)

Lee, Moretti, and Butler (2004)

Motivation

If politicians can commit to their electoral promise...

(as assumed in the Downsian model)

More competitive election forces their policies to converge

to the median voter's bliss point, at least partially

If politicians cannot commit

(as assumed in the citizen-candidate model)

More competitive election has no impact on their policies

("Voters affect policies.")

("Voters elect policies.")

Lee, Moretti, and Butler (2004)

Empirical challenge

Competitiveness of an election: endogenous to politicians' policies

Source of exogenous variation:

Close elections in the previous election

Close elections (nearly) randomly allocate

the winning candidate's party affiliation

Due to incumbency advantage (empirically true in U.S.)

it's also random how competitive the next election is

US House Representatives' roll-call votes, 1946-1995

0

100

Liberal

Conservative

Quantify how liberal voting behaviour is (known as ADA Score)

Lee, Moretti, and Butler (2004)

Data (cont.)

The ADA Score is widely used in political science literature

But it has disadvantages

Scoring can be subjective, possibly influenced by Representatives' party affiliation

Based on about 20 "high-profile" roll-call votes, the choice of which may be arbitrary

Lee, Moretti, and Butler (2004)

Data (cont.)

The authors use several alternative measures

So they can show their findings are not driven

by the particular way of measuring the roll-call vote behavior

DW-NOMINATE data by McCarty et al. (1997)

% of votes that agree with the Democrat party leader

Scores by other interest groups than ADA

Lee, Moretti, and Butler (2004)

Why U.S. House Representatives?

Two-party system

One important assumption of the Downsian model

Democrats and Republicans have different policy positions

Each legislator's votes on the bills are observable

Lee, Moretti, and Butler (2004)

Empirical strategy

Regression discontinuity design

US House constituency x Election year

Democrat's candidate vote share

Indicator for the electoral victory of Democrat's candidate

(1 if \(s_i>0.5\); otherwise 0)

Result #1

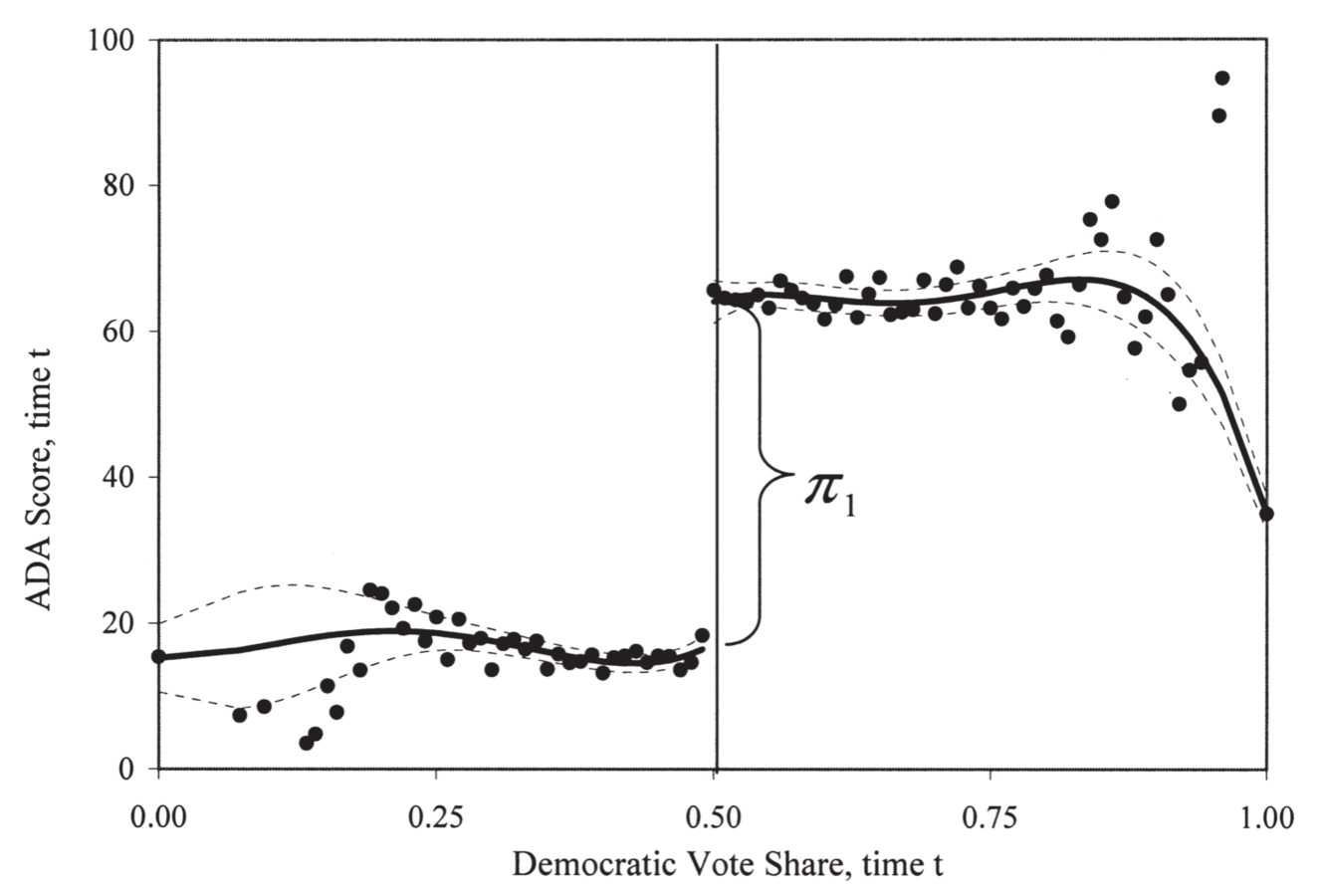

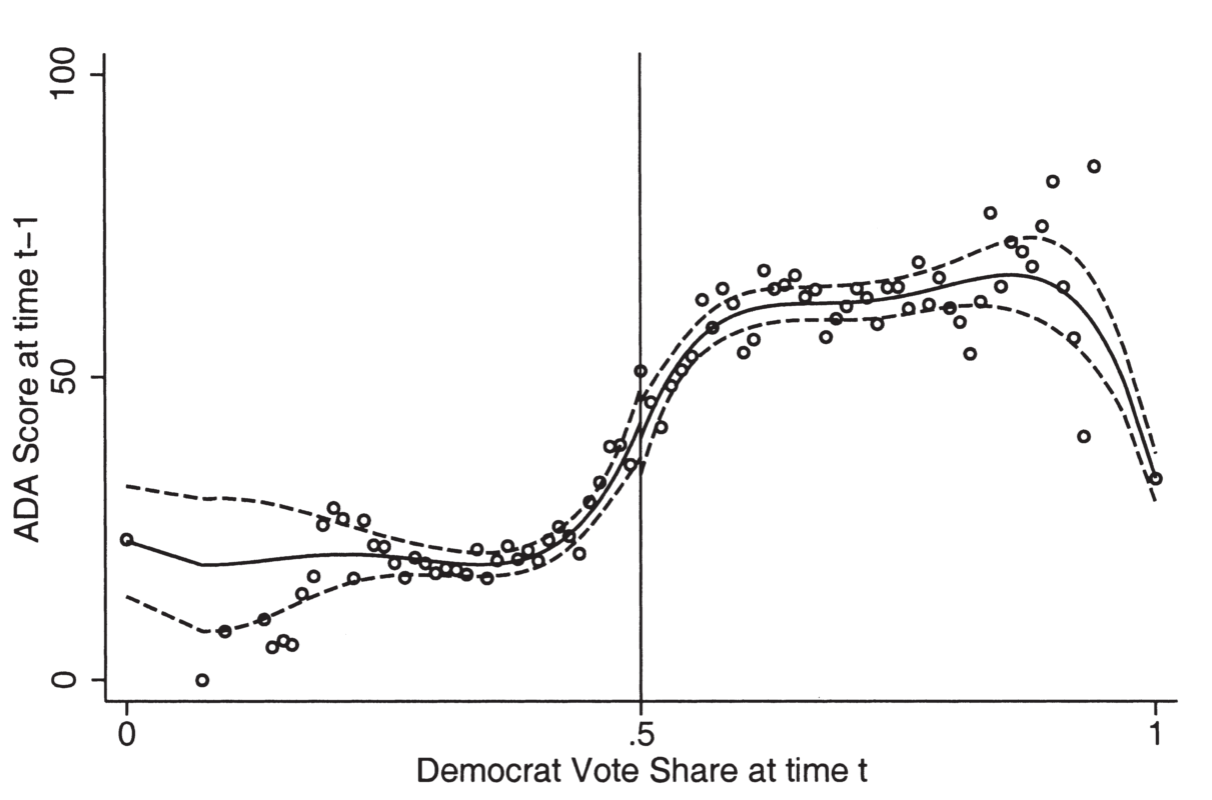

Image source: Figure I of Lee et al. (2004)

the ADA score of the winner at time T+1 by about 20 pts

The election of a Democrat at time T increases

Interpreting Result #1

the ADA score of the winner at time T+1 by about 20 pts

This could mean two things

Democrats are more likely to win at time T+1

and vote according to their own policy preference

Representatives, whether Republican or Democrat,

are forced to promise the incumbent's policy

to win the election at time T+1

The election of a Democrat at time T increases

Source: Figure IIa of Lee et al. (2004)

Result #2

the ADA score of the winner at time T by about 45 pts

The election of a Democrat at time T increases

Interpreting Result #2

the ADA score of the winner at time T by about 45 pts

This finding is against the strict version

of the Downsian model (i.e. full convergence)

For close election districts, the median voter's preference should be similar on average between both sides of the cut-off

If politicians promise the median voter's preferred policy

we shouldn't see such a large difference in voting records

The election of a Democrat at time T increases

Source: Figure IIb of Lee et al. (2004)

Result #3

the probability of electing a Democrat at time T+1 by about 50 percentage points

The election of a Democrat at time T increases

Interpreting Result #1 (cont.)

increases the ADA score of the winner at time T+1 by about 20 pts

The election of a Democrat at time T

This could mean two things

Democrats are more likely to win at time T+1

and vote according to their own policy preference

Representatives, whether Republican or Democrat, are forced to take the incumbent's policy to win the election at time T+1

0.5 x 45 = 22.5 pts

20 - 22.5 = -2.5 pts

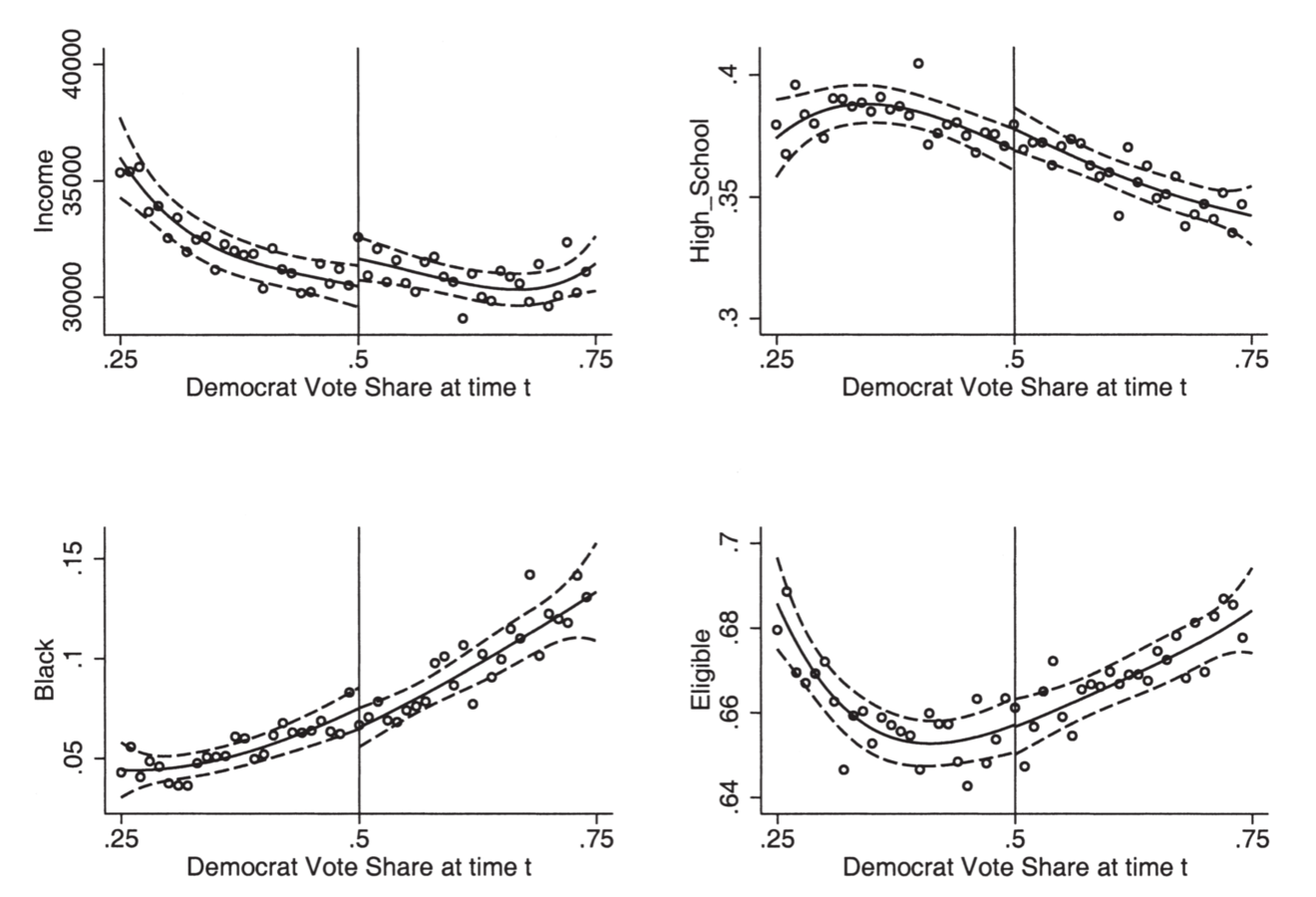

Test for random assignment

The election of a Democrat at time T in close elections

has nothing to do with constituency characteristics

Source: Figure III of Lee et al. (2004)

Income

Education

Race

% of eligible voters

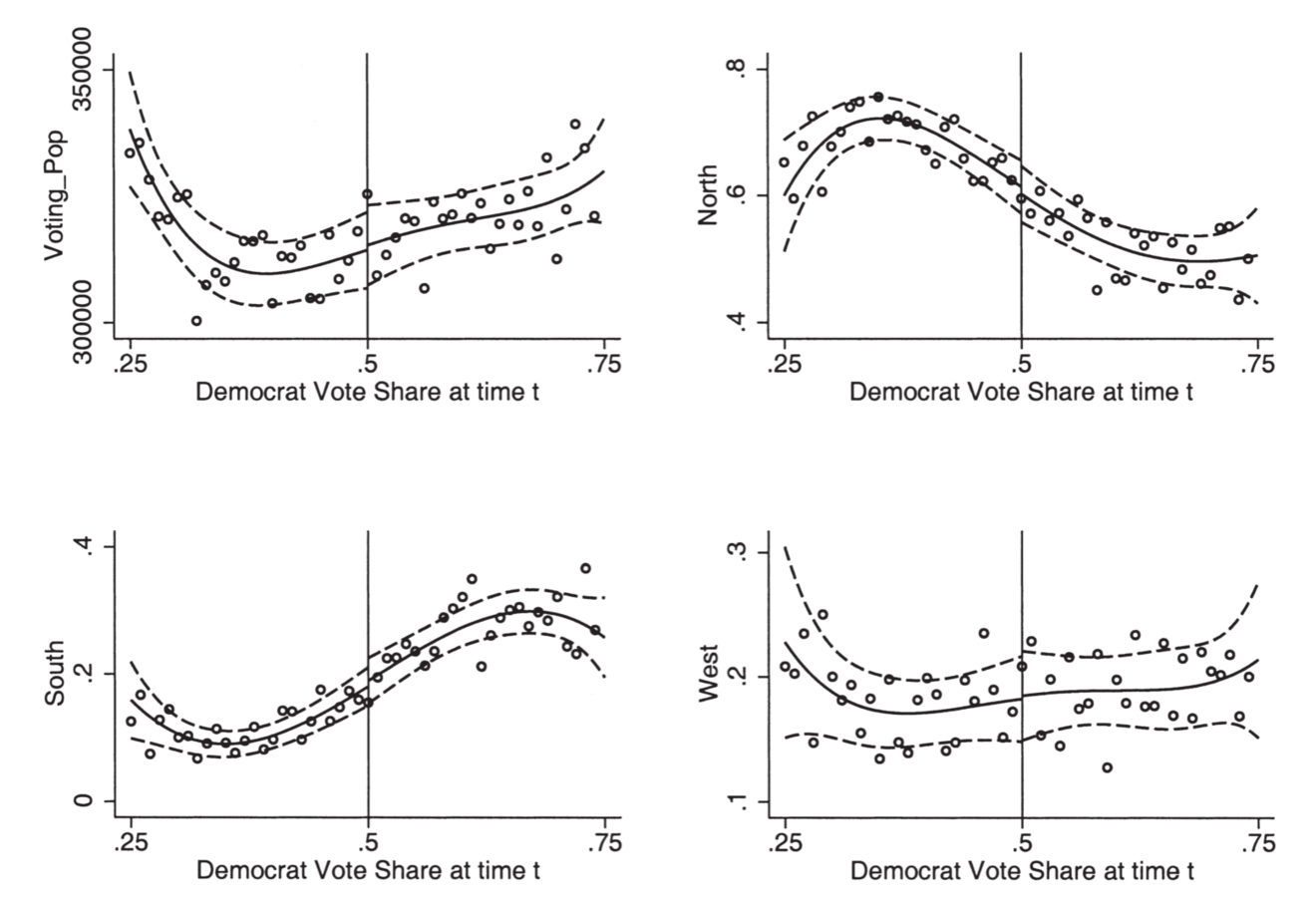

Test for random assignment (cont.)

The election of a Democrat at time T in close elections

has nothing to do with constituency characteristics

Source: Figure IV of Lee et al. (2004)

# of registered voters

% of North districts

% of South districts

% of West districts

Test for random assignment (cont.)

The election of a Democrat at time T in close elections

has nothing to do with legislators elected at time T-1

Source: Figure V of Lee et al. (2004)

Tips for empirical studies: "Placebo tests"

To show the exogeneity of your treatment variable

Replace the dependent variable with

Pre-determined covariates

Outcomes before the treatment is assigned

This applies to any kind of causal inference

RCT

Regression Discontinuity Design

DID

IV

Other evidence for no-commitment assumption

Randomly chosen villages in India:

Village council head position reserved for women

In these treated villages,

more investment in drinking water

(about which women complain more than men)

Other evidence for no-commitment assumption (cont.)

In Indian states, some legislative seats are reserved

for scheduled caste and scheduled tribe candidates

The politician's identity changes

with no change in the electorate's preference

# of reserved seats changes in proportion to their population share according to the latest census

The arrival of new census results

exogeneously change # of reserved seats

Other evidence for no-commitment assumption (cont.)

Pande (2003) (cont.)

Panel regressions of Indian states for 1960-1992 show:

A rise in # of reserved seats in state legislature

Fiscal transfer to these disadvantaged groups

New research agenda: Political Selection

Thanks to the citizen-candidate model (and its supportive evidence)

Economists become increasingly interested in

Who becomes a politician?

This new research agenda is now known as political selection

Literature on Political Selection

Higher politicians' wage

Evidence from regression discontinuity design:

Lower federal transfer to municipalities

What attracts competent people into politics?

Party leader's incentive

How parties affect the competence of candidates

Electoral competitiveness

Electoral rules

Too much campaign contributions

What prevents voters from electing competent candidates

Relatives of re-elected politicians

Who run for office?

Runners-up in the previous election

Politicians in non-democracy: less educated than in democracy

Political selection in non-democracy

Connections and Performance in China

All ethnic groups are represented in cabinets in Africa

Data issues

Data challenges to study political selection

Information on non-elected candidates and all citizens

Who runs for office among the population?

Which candidates do voters select?

Measuring the quality of politicians

Education / pre-office income may just reflect luck

Measuring representation

Need for information on social class, not pre-office occupation

Sweden provides such data

All residents in Sweden are assigned the personal ID number

by the tax authority (since 1947)

This ID numbers allow researchers

to match any micro datasets on Swedish population

e.g.

Logging in to online banking

requires the personal ID number

Data on non-elected candidates and population

Dal Bo et al. (2017) compile the following data

All elected and non-elected candidates for national and municipal legislatures during 1982-2010 (over 200,000 in total)

Ranked by political parties as party list in PR system

Provided with personal ID number

Administrative data for the whole population on

age, sex, years of education, occupation, earnings

Linked via personal ID number to candidate lists

Information on non-elected candidates and all citizens

Municipal councilors in Sweden

72% of MPs used to be elected for a municipal council

cf. 29% for MPs in Japan (source: http://finchsuisatsu.seesaa.net/article/419477163.html)

spends 25% of GDP

employs 20% of workforce

for K-12 education, child care, elderly care, local infrastructure

by financing them from a local income tax of 20%

Municipality govt

Municipal councilors

"Leisure politicians" (except for mayors)

Election campaign cost financed by tax money (via party)

Data on competence

Dal Bo et al. (2017) compile the following data

Obtain Earnings Score as residual from Mincer regression

Information on the quality of politicians (and population)

For all men, a mandatory draft gives

Cognitive score (equivalent of the IQ test score)

Leadership score (equivalent of the Big 5 Personality Traits)

Data on competence (cont.)

Pairwise correlation of years of education with

Earnings score: 0.076

Cognitive score: 0.51

Leadership score: 0.30

Education: only one of several dimensions of competence

For all Swedish men in 2011...

Data on representation

Dal Bo et al. (2017) compile the following data

Multigenerational Register to identify

Siblings

Biological father (and mother)

Information on social class / family background

Stylized facts on Swedish politicians

In this lecture we focus on Earnings Score as the ability measure

But the findings are similar for cognitive/leadership scores

Fact #1: Politicians are smarter than population

Source: Figure I of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Source: Figure I of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Stata command)

rejects the equality of distributions for every pair of categories

Comparison to high-status professions

Municipal councilors: similar to small-firm CEOs

Mayors: similar to medium-firm CEOs

MPs: similar to lawyers, below doctors and large-firm CEOs

Source: Table II of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Fact #2: Politicians are smarter than their siblings

Municipal councilors

Source: Figure II of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Mayors

Source: Figure II of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Fact #2: Politicians are smarter than their siblings

MPs

Source: Figure II of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Fact #2: Politicians are smarter than their siblings

Fact #2: Politicians are smarter than their siblings

It's not that

both politicians and smart individuals

come from high social class ("Elitism")

Conditional on social class (i.e. sibling fixed effects)

those smarter become politicians

Fact #3: Politicians come from families across the whole income spectrum

Source: Figure IV of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Income distribution of fathers of each occupation

Fact #3: Politicians come from families across the whole income spectrum

It's not that

being smart to become politicians

requires being born in high social class

("Exclusive Meritocracy")

Smarter people become politicians

Politicians represent the whole spectrum of social class

How can this be possible?

Fact #4: Stronger selection for lower social class

Ability gradient across class flattens

as moving up the political career ladder

Source: Figure VII of Dal Bo et al. (2017)

Additional evidence

on the decision to become a candidate

A positive correlation across municipalities

btw. mayor's wage & candidate ability

(Appendix Figure A.5)

A negative correlation across occupations

btw. age-earnings profile steepness & candidate ability selection

(Appendix Figure A.6)

It's not purely a story of intrinsic motivation

Additional evidence on who gets elected

A positive correlation btw. party list rank & candidate ability

(Figure VIII)

Political parties screen candidates by competence

Summary

High wage to be a mayor / an MP as well as intrinsic motivation

attracts smart individuals into politics

Low cost of entry ("leisure politicians") seems also key

Political parties screen candidates by competence

Positive selection into politicians is stronger for low social class

Swedish politicians are:

(1) Smarter than the population

(2) Representative of all social classes

Applications of

Citizen-candidate Model

Incorporate lobbying

Media's role in dertermining which policy is salient in elections

Elected versus appointed regulators

Some examples

Another application: Why political parties exist?

Other theories of political parties

Political parties aggregate information on which policies are correct

Endogenize # of political parties under different electoral rules

Today's take away

The Downsian paradigm is hard to defend

given the accumulation of causal evidence.

The identify of politicians does matter for policy-making.

So we need to figure out who becomes a politician

for better-understanding of policy choice.

Political Economics lecture 2: Citizen Candidate Model

By Masayuki Kudamatsu

Political Economics lecture 2: Citizen Candidate Model

- 2,781