Bibliographies and Literature Reviews

Benjamin Lind

International Laboratory for Applied Network Research

September 30, 2014

Primary Considerations

- Know your audience

- Positioning the fulcrum to leverage your research

- General vs. specific

- Intradisciplinary vs. interdisciplinary

- Theoretical vs. methodological

- Recent vs. classic

- Academic vs. practitioner

- Model after one published work

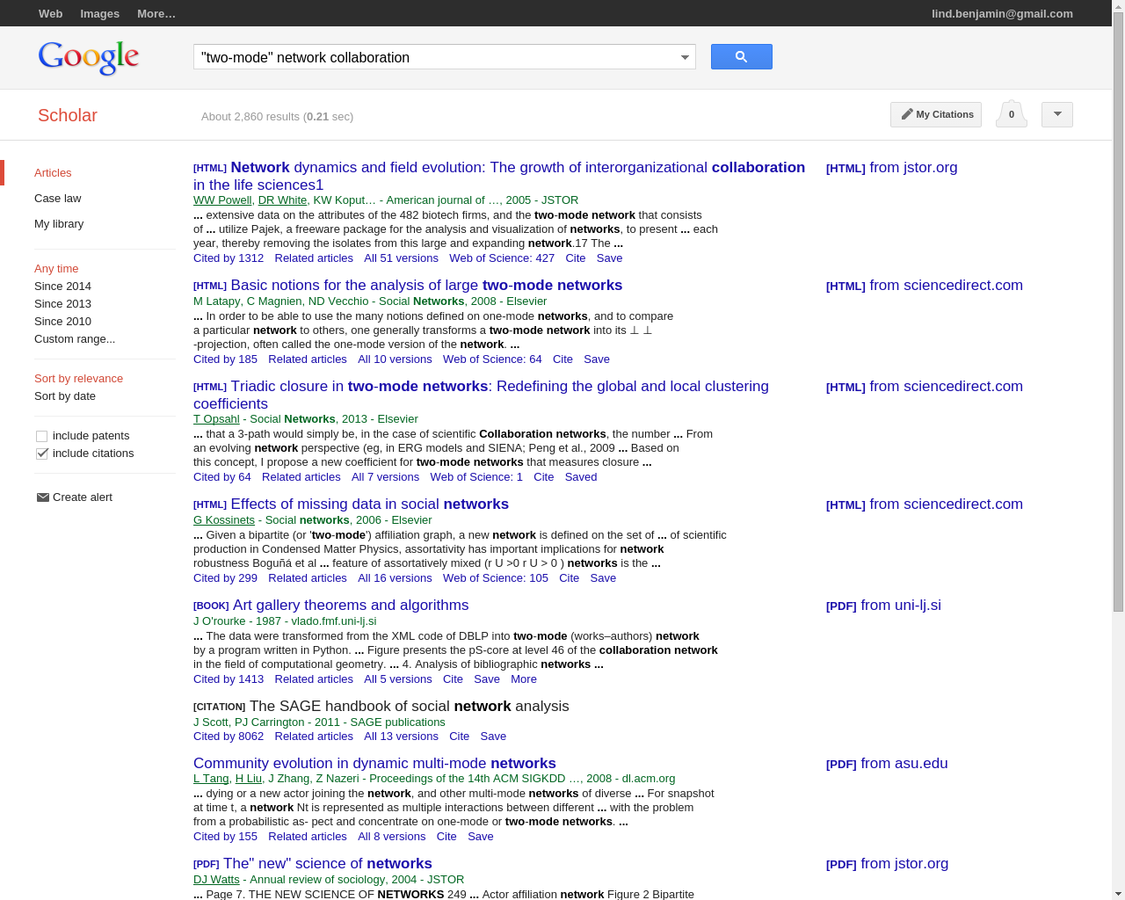

Semantic Search

- Presuppose concepts can be expressed in a common vocabulary

- Search with keywords

- Ideally ~10 - 50 results

- Some hits, some misses

- Read the hits

- Refine keywords, repeat

Network Search

- Presuppose research is a networked phenomenon

- Citation practices form a directed, acyclical, two-mode network

- Begin search with relevant central actors (authors) and events (articles)

- Follow relevant paths from starting point

- Pros: Exploration, novelty.

- Cons: Depends upon correct keywords. Semantics ignore academic traditions.

- Pros: Potentially very efficient, comprehensive.

- Cons: Depends upon good starting points.

Most research involves both

- Start with semantic searches.

- Move to network searches once you have a start.

- If the network becomes too big:

- conduct a semantic search within it.

- confine criteria to recent articles.

Starting Cold

For when you have no idea where to start...

Steps

- Break up problem into pieces

(think general topics) - Identify core works within pieces

- Review articles

- Highly cited works

- Works published in prominent journals

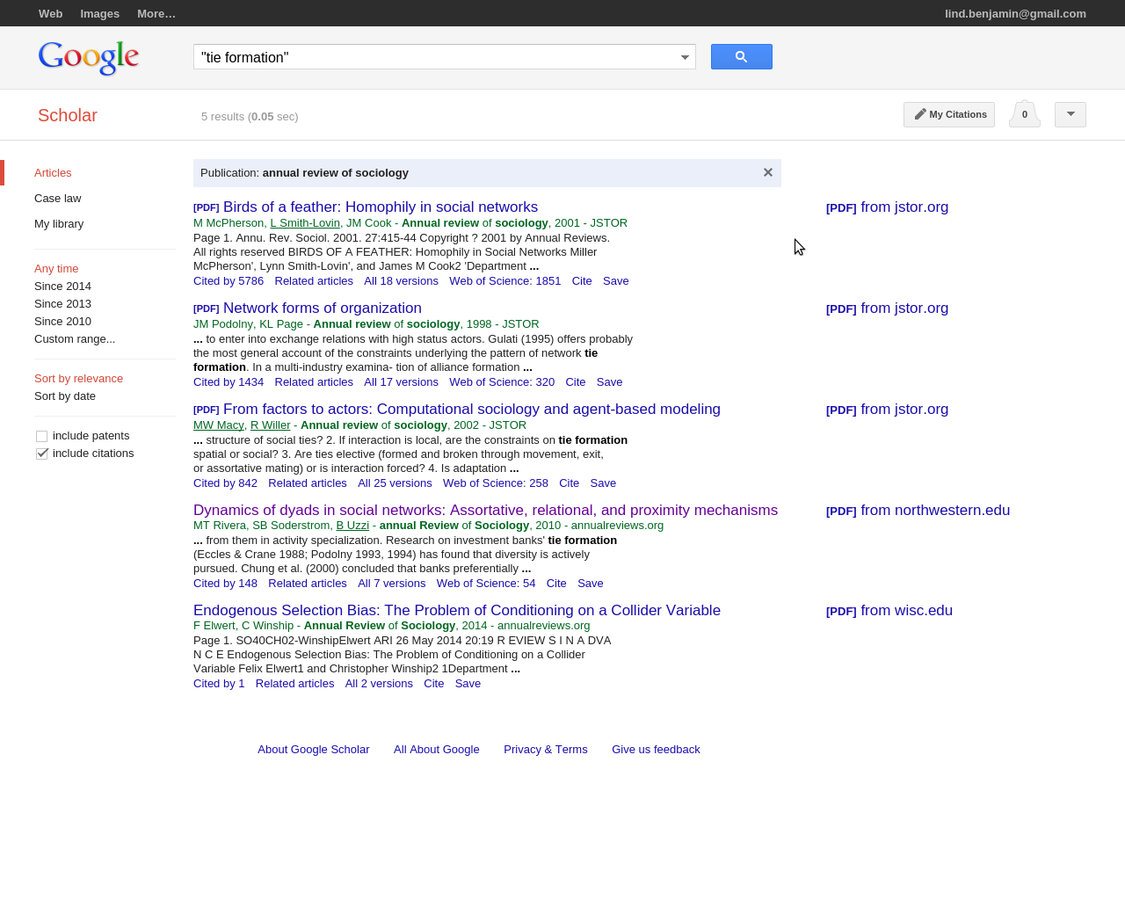

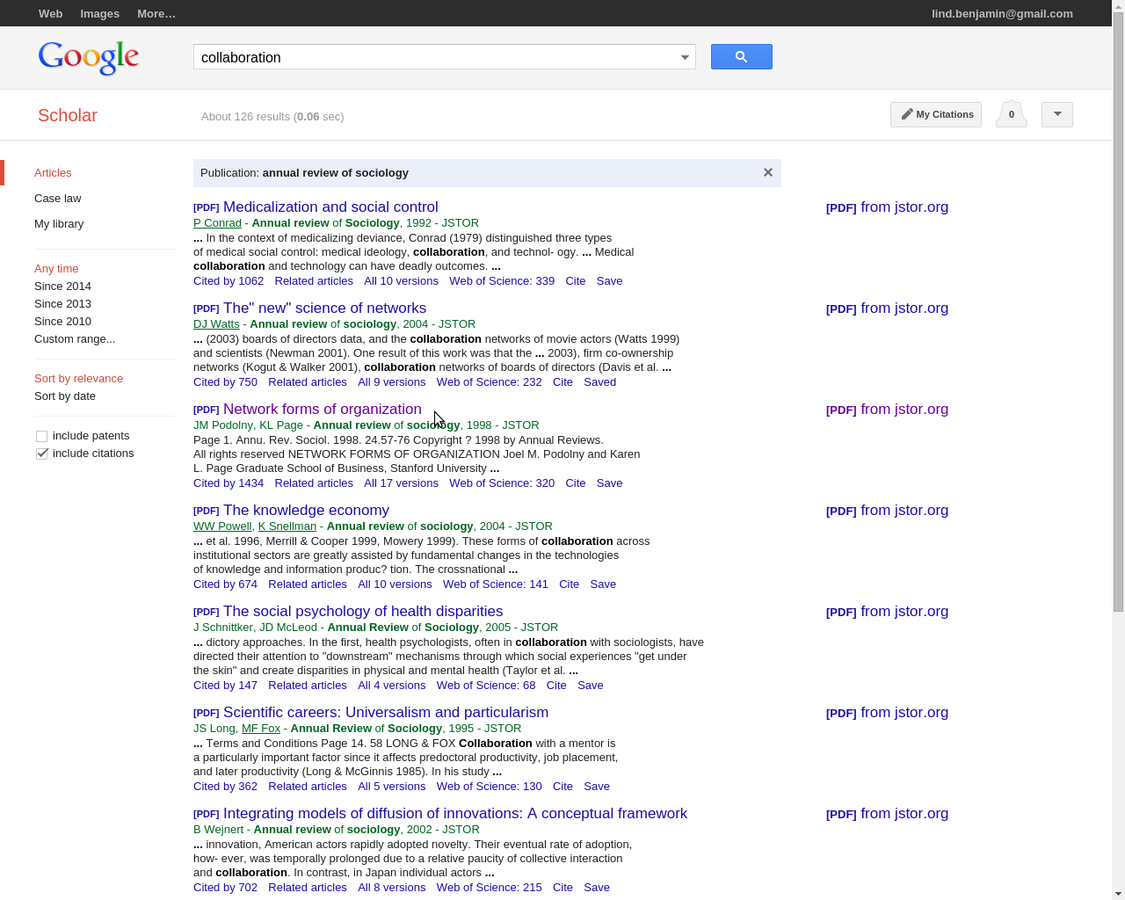

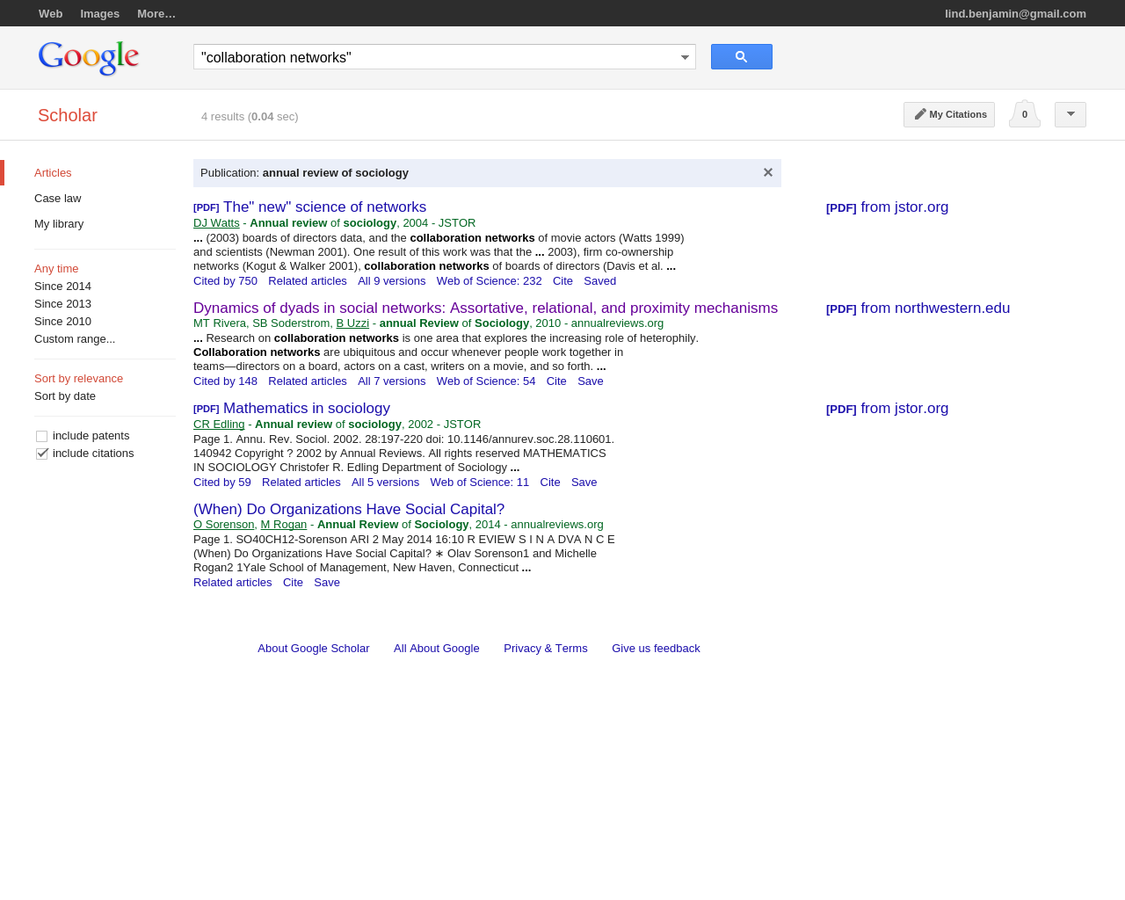

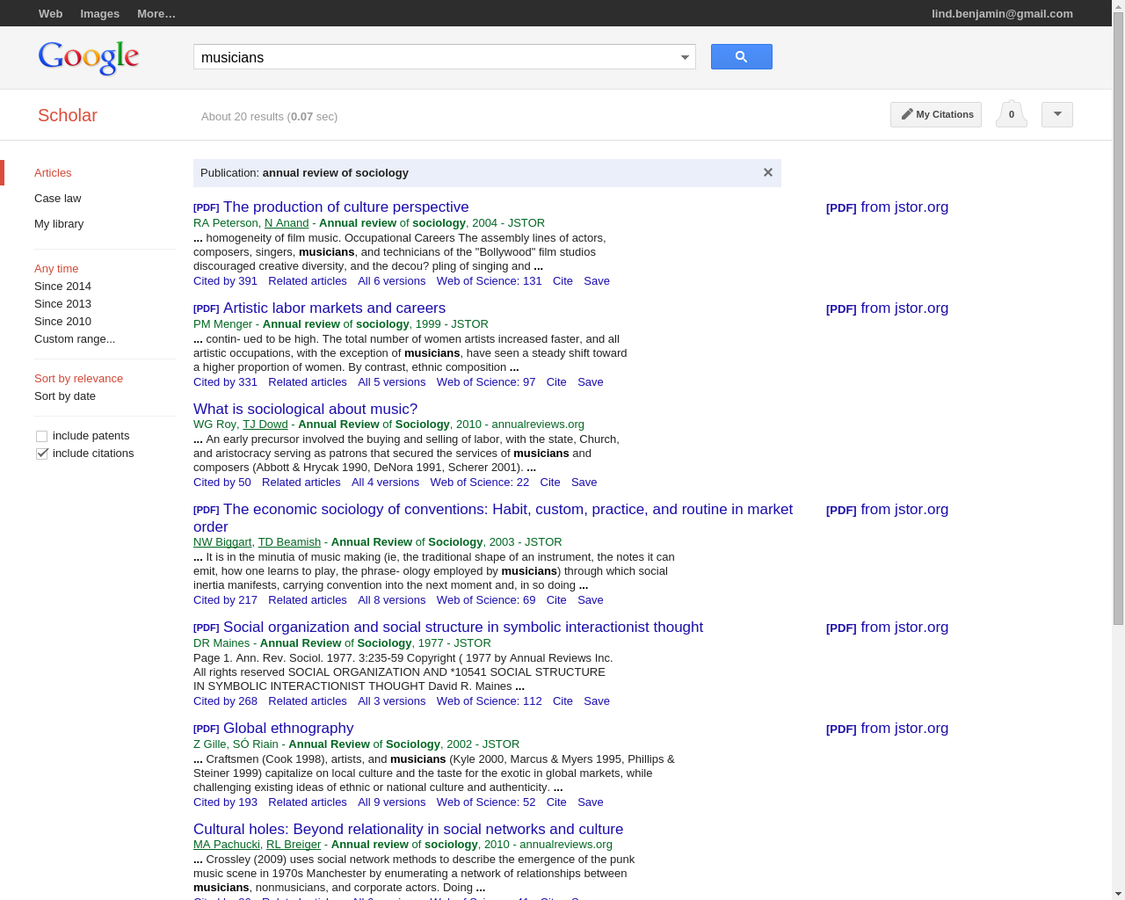

Example

How do musicians playing jazz and metal form collaborative ties?

- Pieces

- Tie formation

- Collaboration

- Two-mode networks

- Teams?

- Musician networks

- Case specifics

- Jazz history

- Metal history

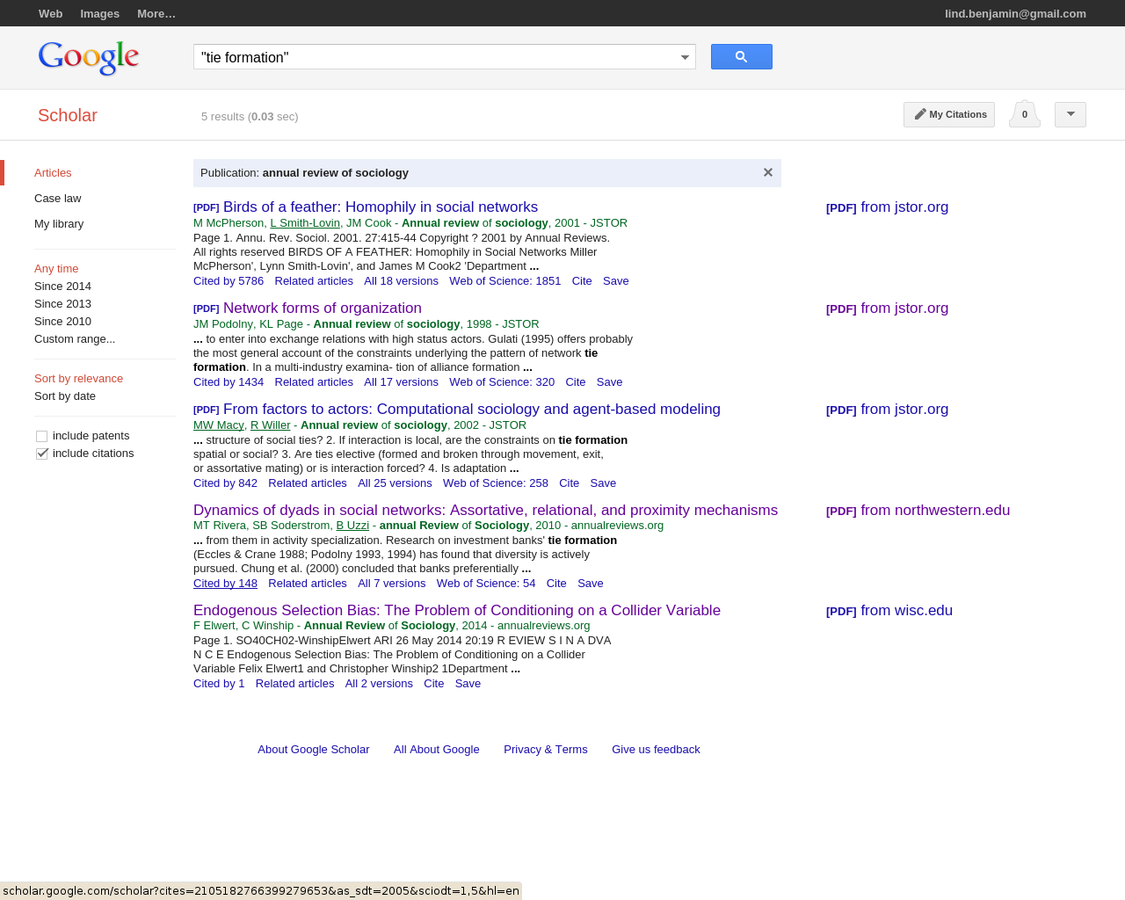

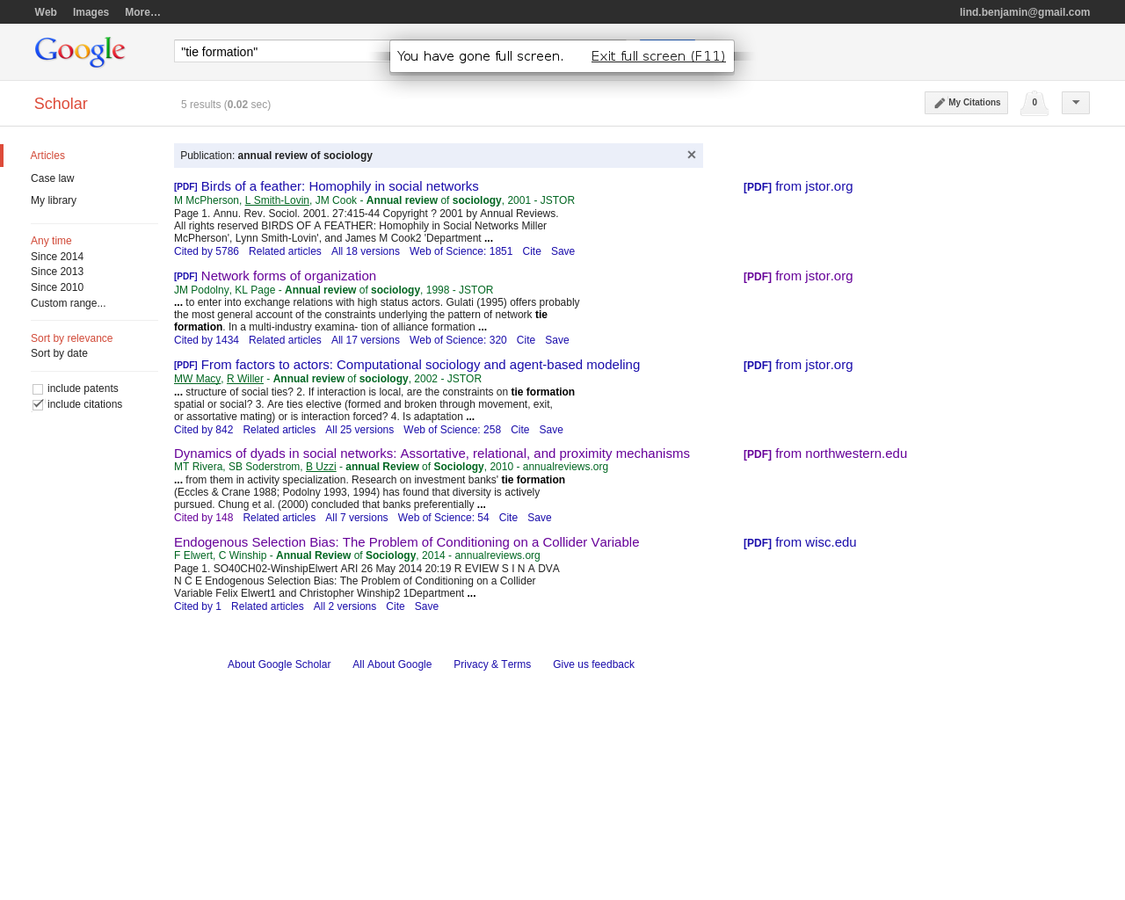

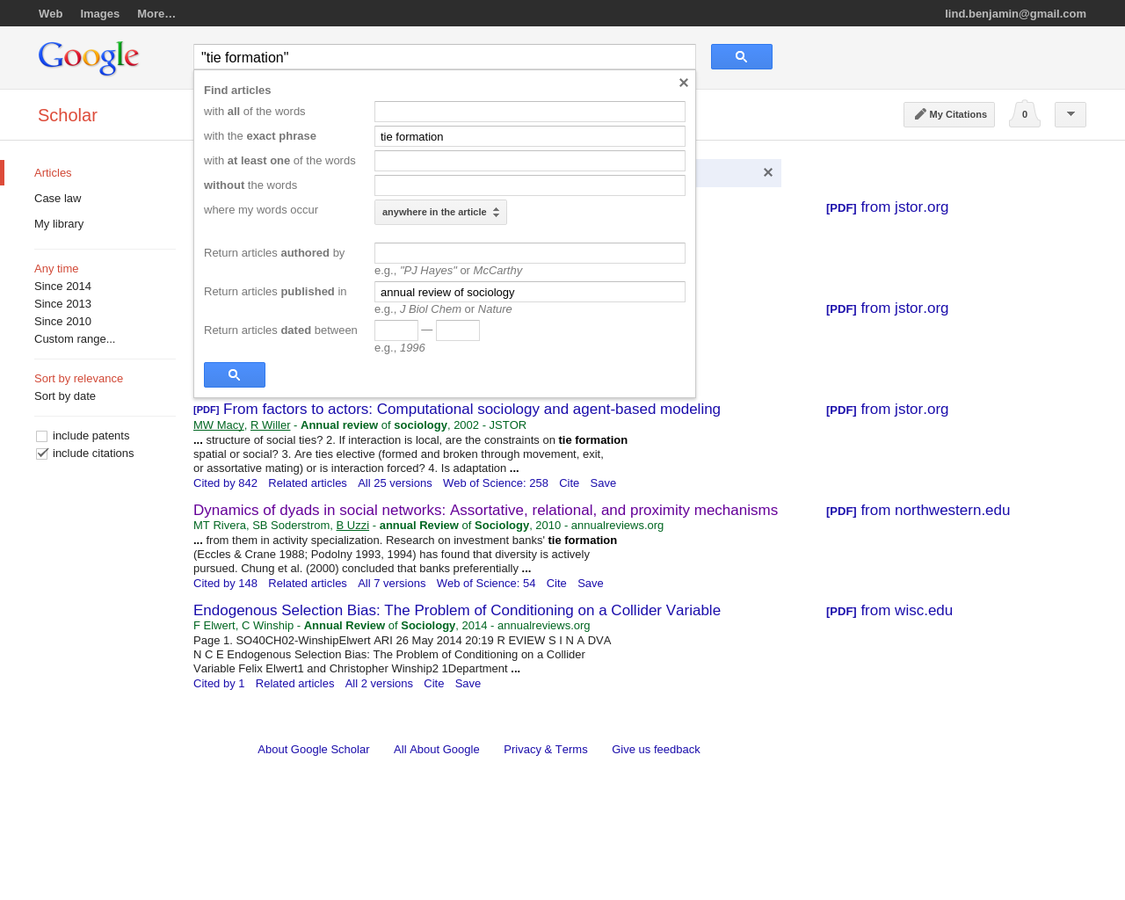

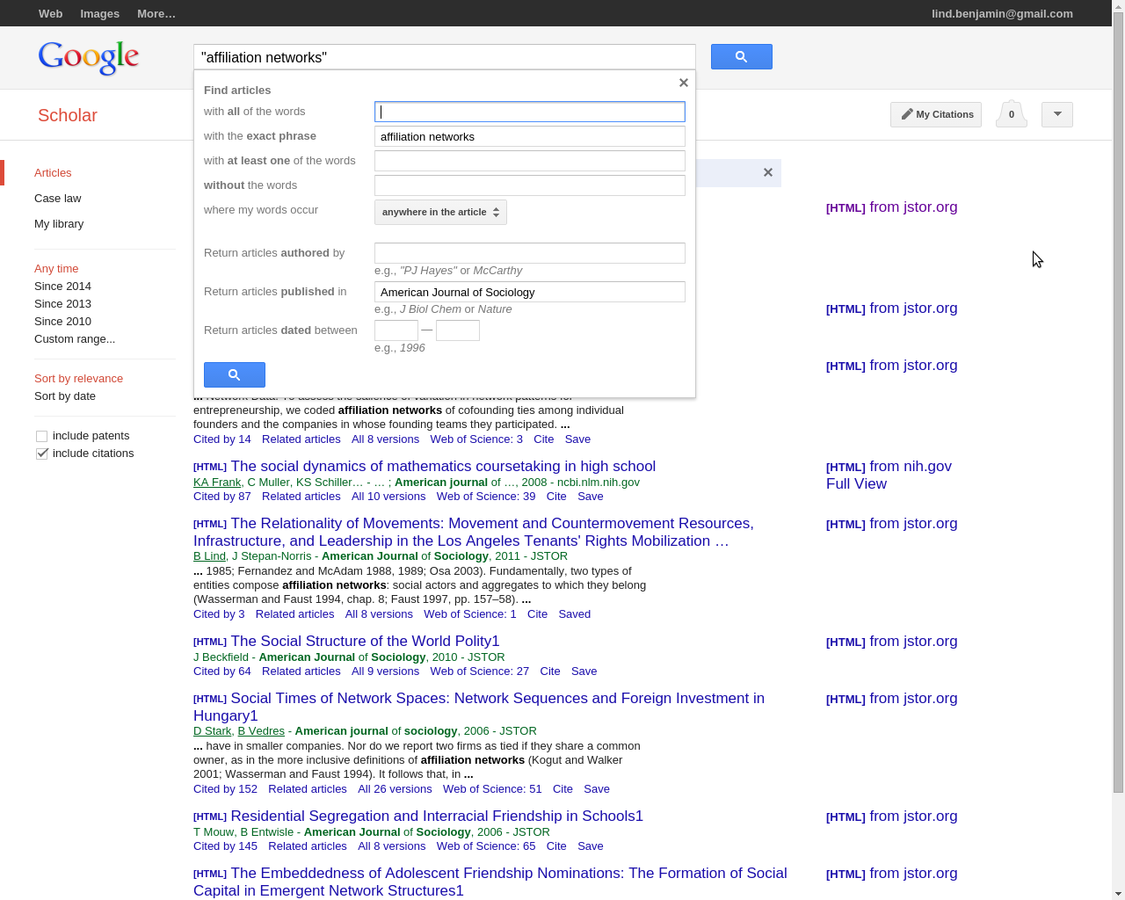

Identifying Core Works

See if someone has already written a literature review

- Go to Google Scholar

- Enter key terms

- Specify the review journal

(See annualreviews.org)

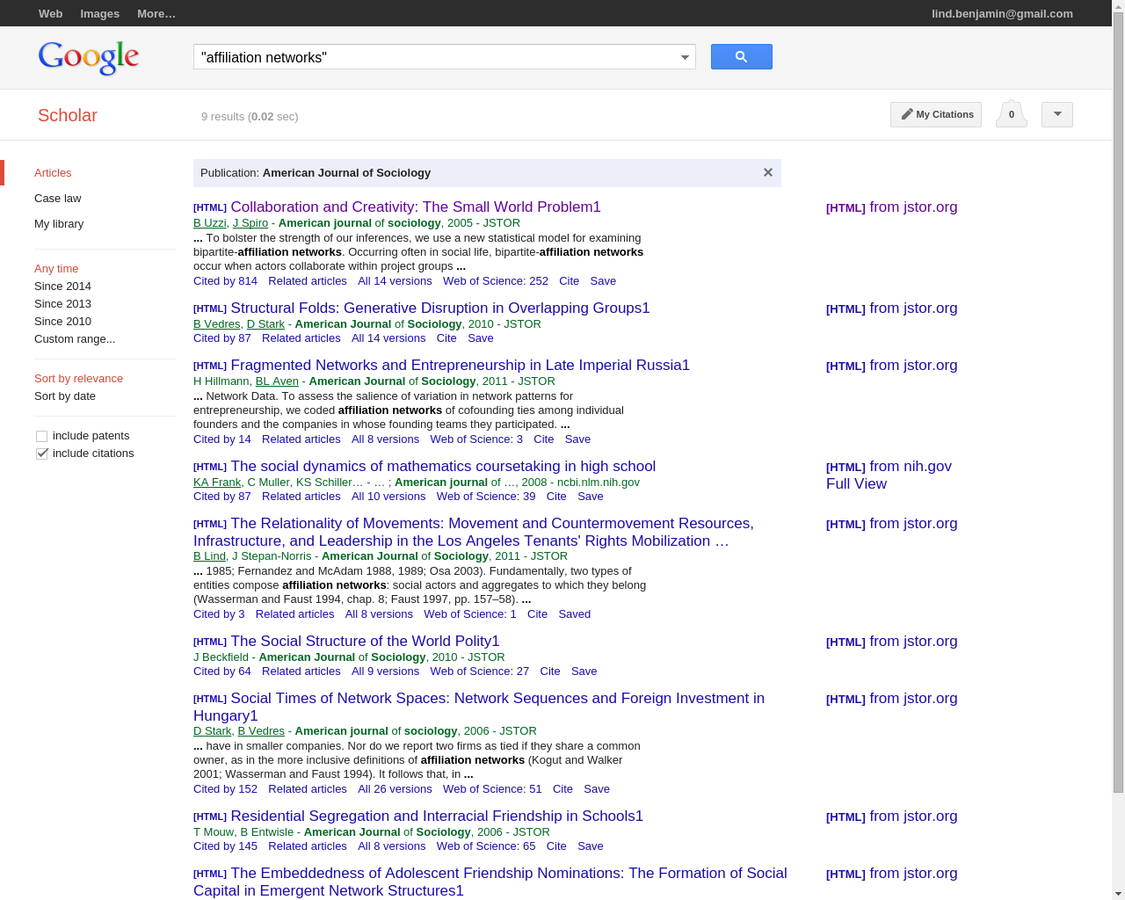

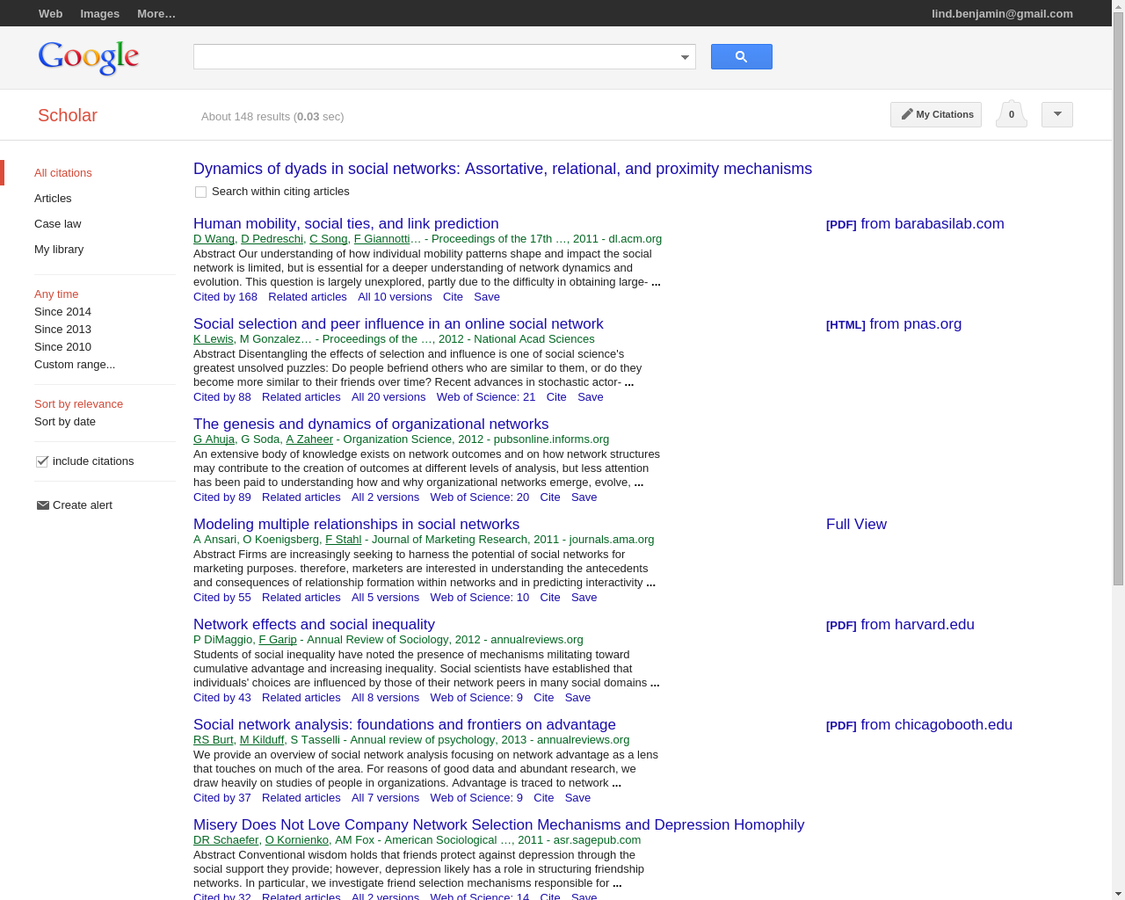

Identifying Core Works

See what's highly cited

- Your audience will expect it

- It has likely guided relevant knowledge

This article has come up many times before...

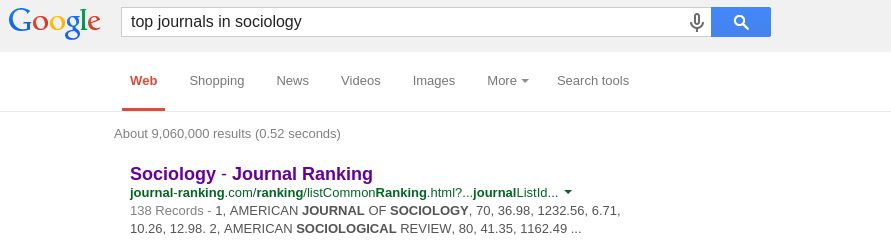

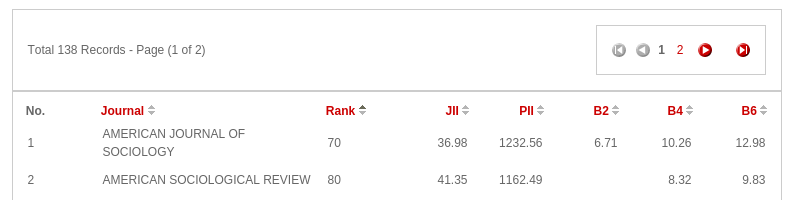

Identifying Core Works

Check the "top" journals your audience reads

- Journal rankings can be extremely subjective

- If you do not know the rankings, LMGTFY

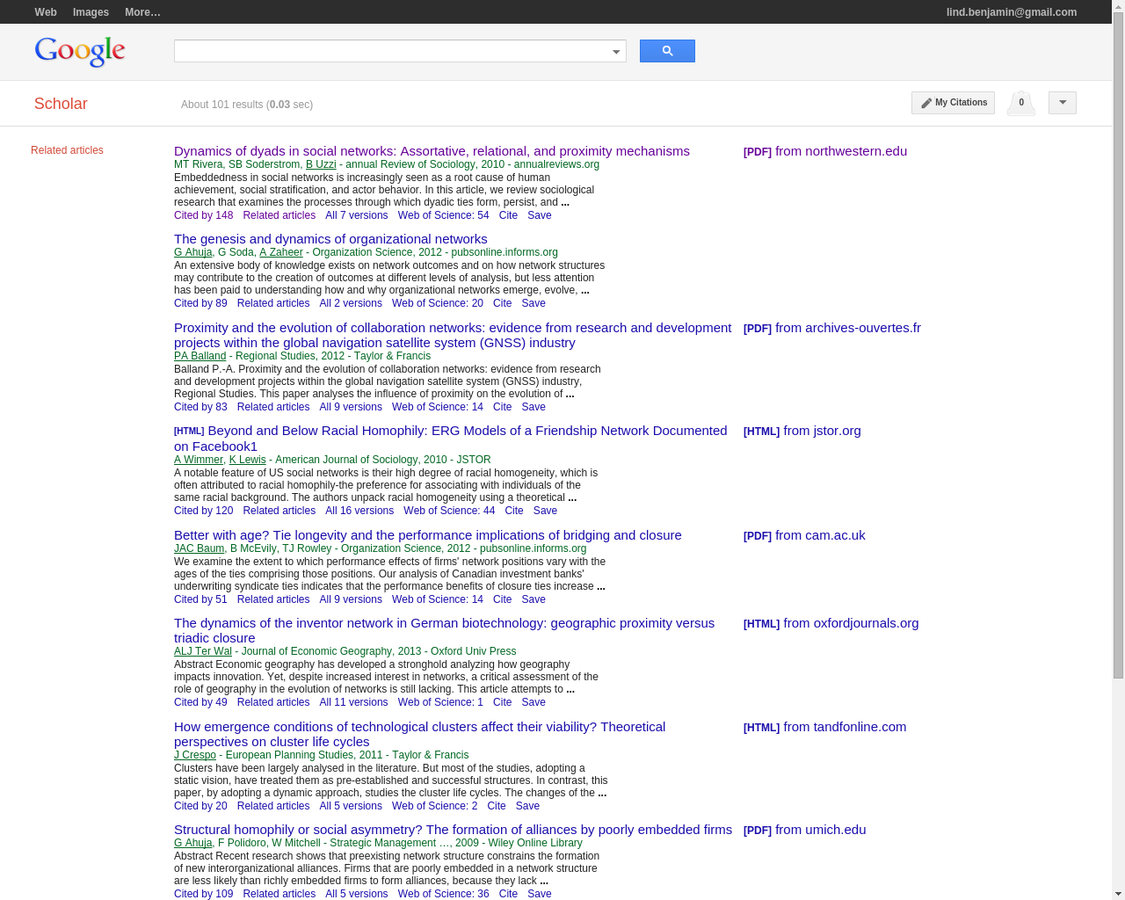

Knowing the Field

After you have identified your key, initial citations...

For each key article

- Search backward

- Search forward

- Search by author

- Browse "related articles"

- Repeat recursively until satisfaction

(i.e., relevant, novel information dead-ends)

Search Backward

Who did the key piece cite?

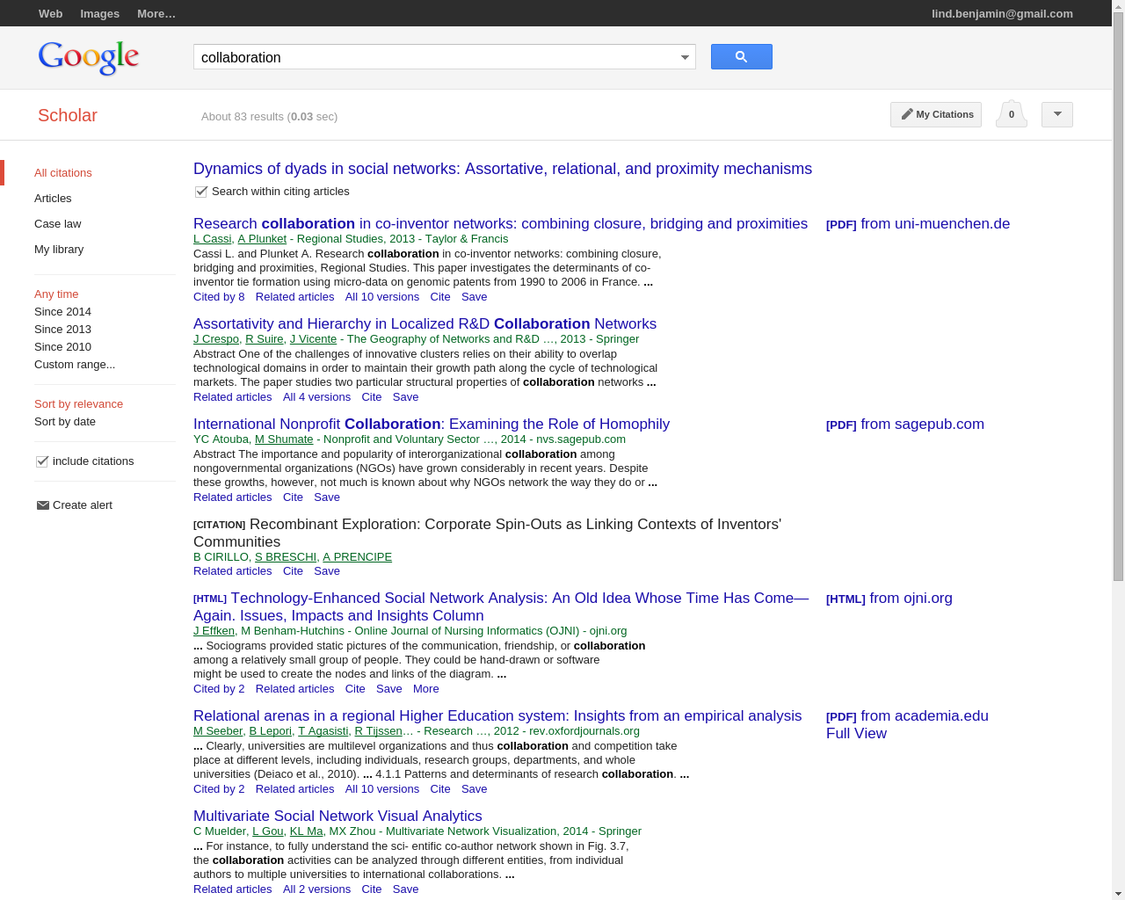

Search Forward

Who cites the key piece?

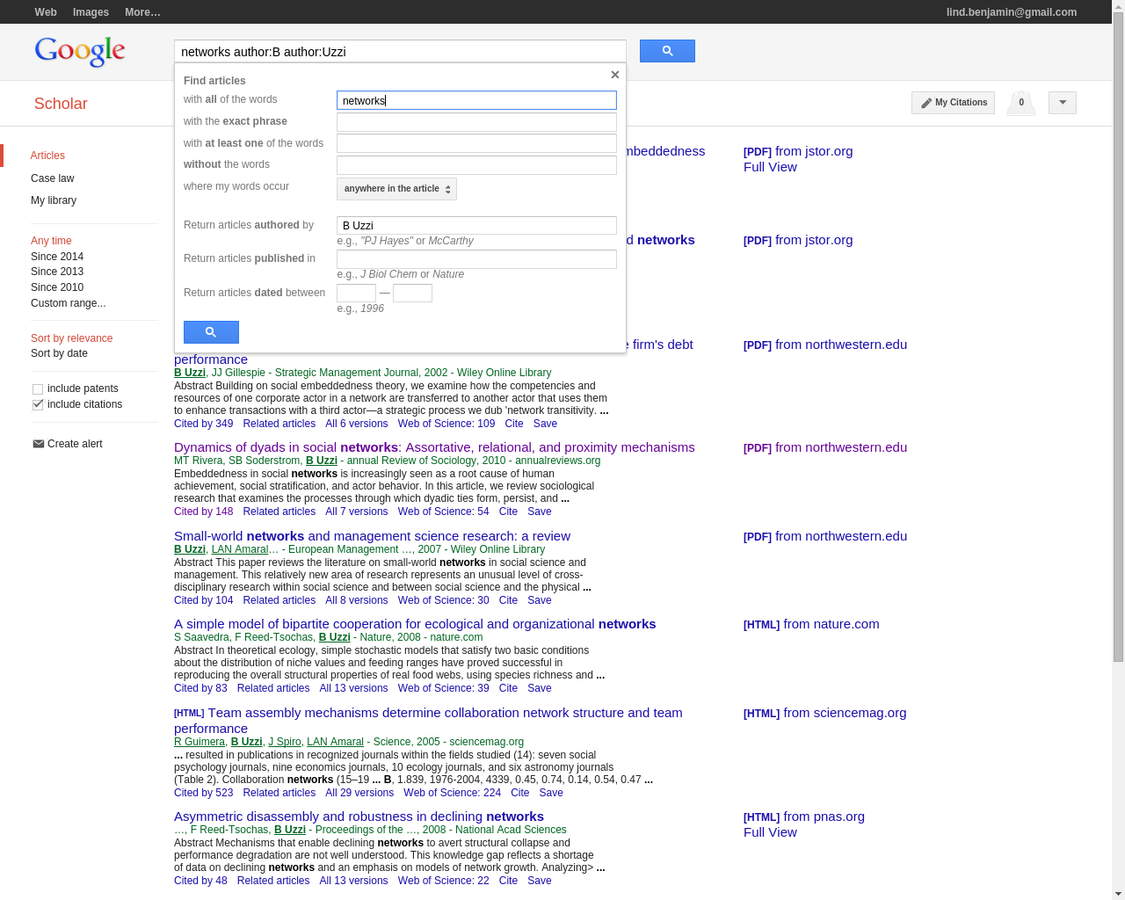

Search by Author

Has the author worked on similar problems?

Browse Related Articles

Does Google's 'related' algorithm know something I don't?

Repeat Recursively

Follow the network path...

- Discover competing concepts

- Bridge overlapping concepts

- Stop after meeting either of these criteria

- No novel information

- No relevant information

The Hard Part

You need to know the articles and their place in the literature.

- Read the articles carefully

- Discard the irrelevant

- Understand their main arguments

- Organize these arguments into themes

- Literature review write-up

- Biggest themes deserve subheaders

- Small themes deserve paragraphs or sentences

Reading tips

Organizational tips

Write-up tips

Problem

- Too few authors cited.

- Most citations older than five years.

- Passage has weak relationship to cited article.

- Family of literature absent.

- No cohesion, conceptual overlap among citations.

What it means

- Nobody else cares.

- Old paper, old ideas, lazy search, no longer relevant.

- Lazy reading or lazy writing. Probably both.

- Lazy. Didn't do homework.

- No agreement within subfield.

What are some other problems?

ANRBibliographies2014

By Benjamin Lind

ANRBibliographies2014

- 3,154