Consistency and Consensus

What can happen?

- packets can be lost, reordered, duplicated, or arbitrarily delayed in the network

- clocks are approximate at best

- nodes can pause (e.g., due to garbage collection) or crash at any time

Linearizability

Other names: atomic consistency, strong consistency, immediate consistency, external consistency.

idea is to make a system appear as if there were only one copy of the data, and all operations on it are atomic. With this guarantee, even though there may be multiple replicas, in reality, the application does not need to worry about them.

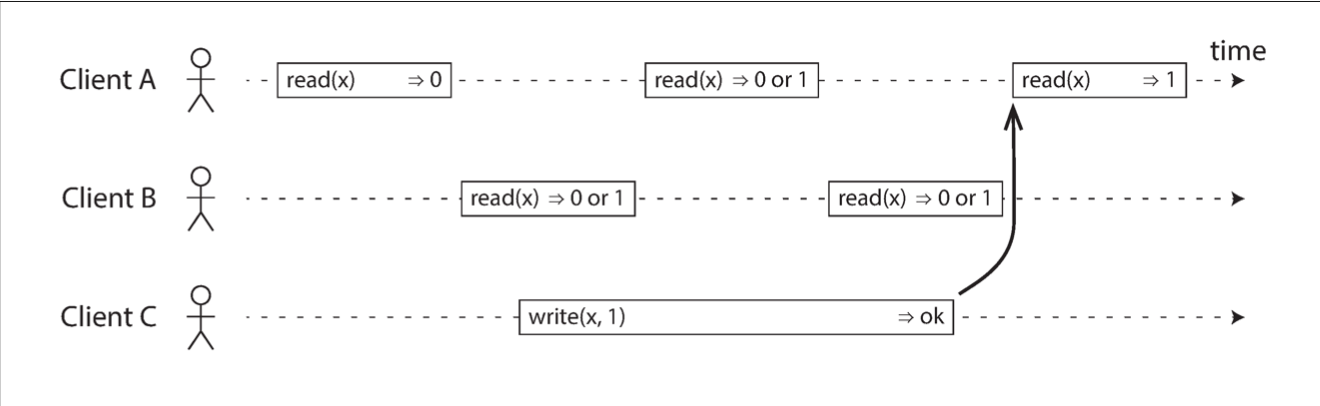

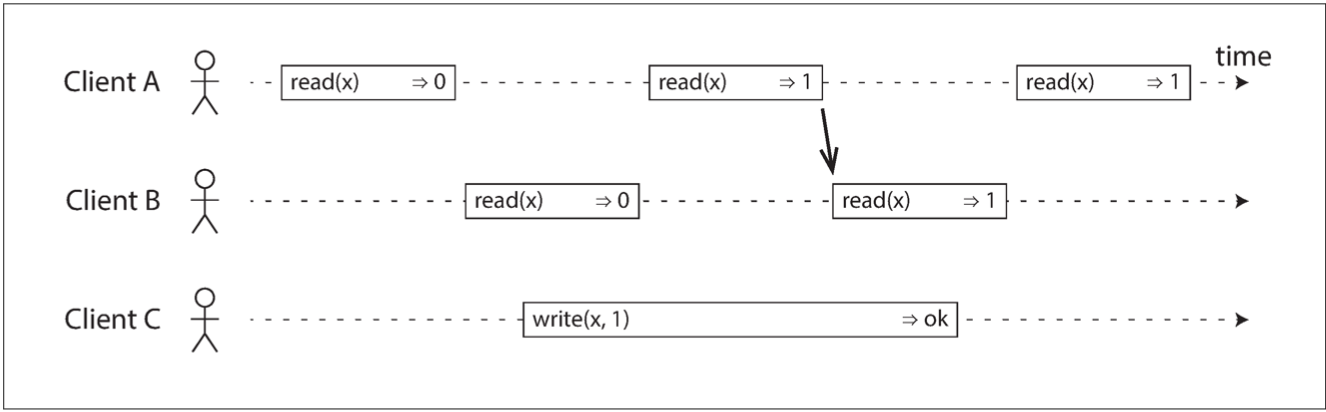

Any read operations that overlap in time with the write operation might return either 0 or 1, because we don’t know whether or not the write has taken effect at the time when the read operation is processed. These operations are concurrent with the write.

Other names: atomic consistency, strong consistency, immediate consistency, external consistency.

idea is to make a system appear as if there were only one copy of the data, and all operations on it are atomic. With this guarantee, even though there may be multiple replicas, in reality, the application does not need to worry about them.

In a linearizable system we imagine that there must be some point in time (between the start and end of the write operation) at which the value of x atomically flips from 0 to 1. Thus, if one client’s read returns the new value 1, all subsequent reads must also return the new value, even if the write operation has not yet completed.

Serializability vs Linearizabiity

Serializability is an isolation property of transactions guarantees that transac‐ tions behave the same as if they had been executed in some serial order

Linearizability is a recency guarantee on reads and writes of a record

A database may provide both serializability and linearizability, and this combination is known as strict serializability or strong one-copy serializability (strong-1SR)

Two-phase locking (2PL) and actual serial execution are typically linearizable

Serializable snapshot isolation is not linearizable: by design, it makes reads from a consistent snapshot

Use Cases

Locking and leader election: One way of electing a leader is to use a lock: every node that starts up tries to acquire the lock, and the one that succeeds becomes the leader. No matter how this lock is implemented, it must be linearizable: all nodes must agree on which node owns the lock; otherwise, it is useless.

Constraints and uniqueness guarantees: unique user name; bank account balance never goes negative guarantee; do not sell more items than having in stock; book a seat in flight or theater

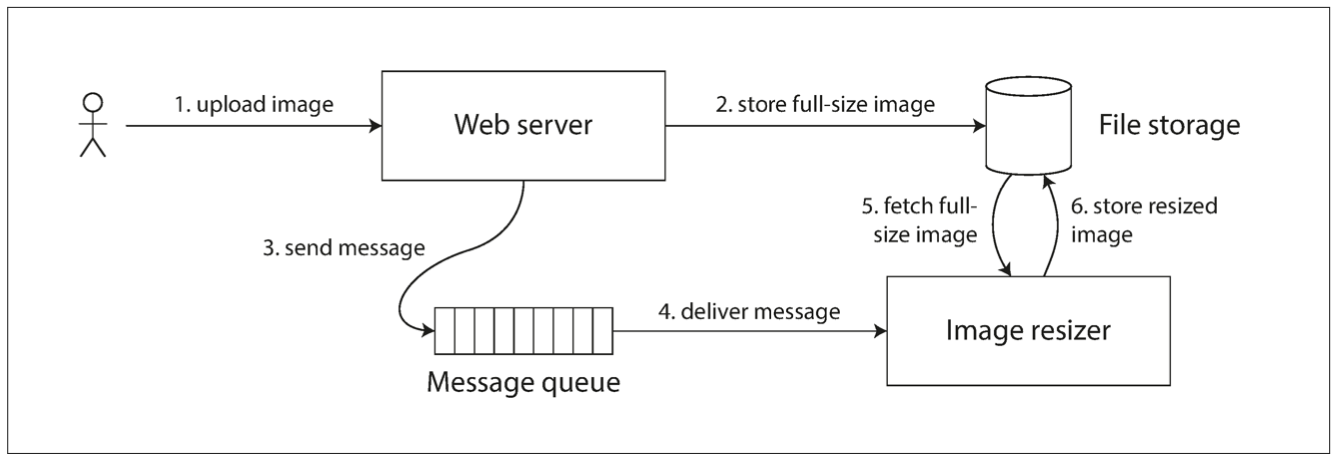

Cross-channel timing dependencies: Image resizer might get a stale read

Who can be linearizable?

Single-leader replication (potentially linearizable) - If you make reads from the leader, or from synchronously updated followers, they have the potential to be linearizable.

Though a node might think it's a leader when it's not. And with async replication, failover may lose committed writes.

Consensus algorithms (linearizable)

Multi-leader replication (not linearizable) - they concurrently process writes on multiple nodes and asynchronously replicate them to other nodes. For this reason, they can produce conflicting writes that require resolution.

Who can be linearizable?

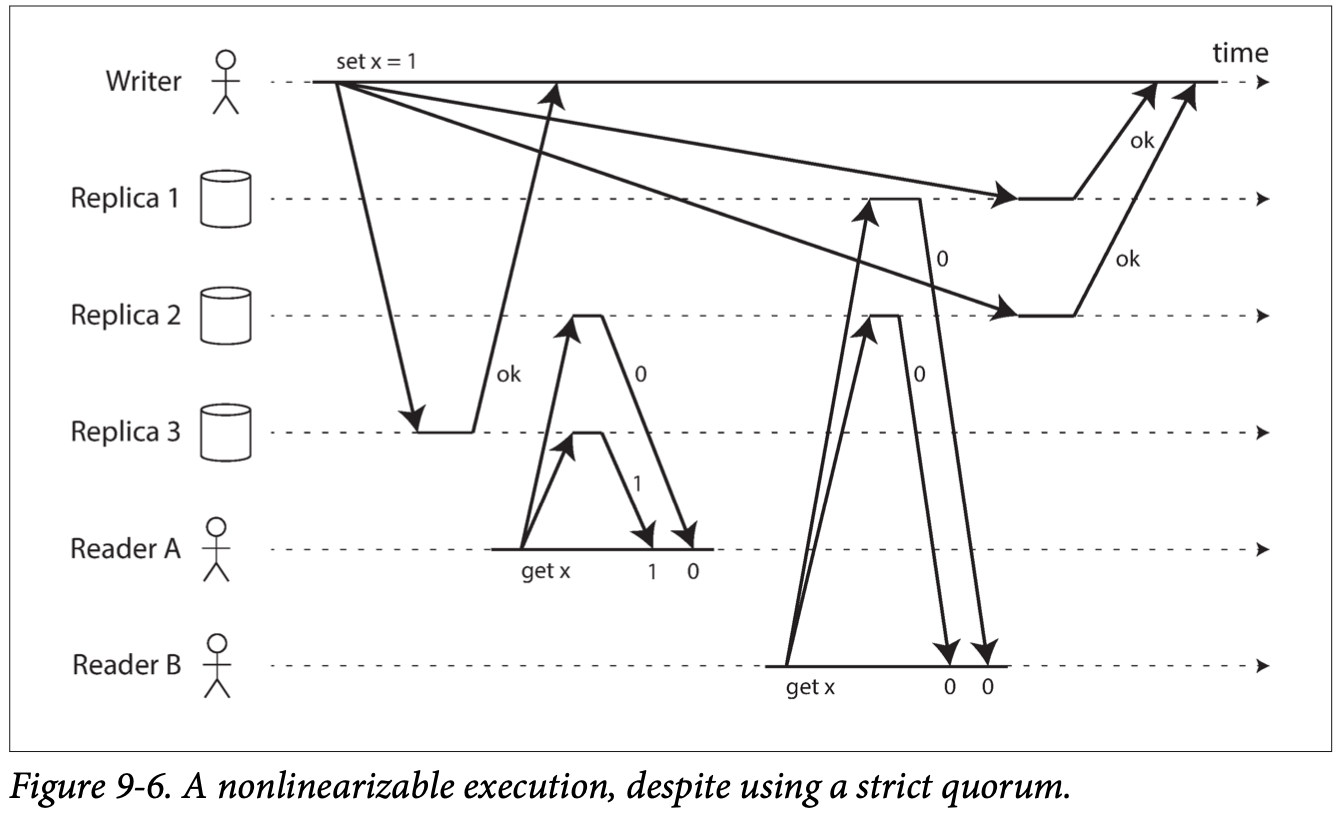

Leaderless replication (probably not linearizable): “Last write wins” conflict resolution methods based on time-of-day clocks (e.g., in Cassandra) are almost certainly non-linearizable. Sloppy quorums also ruin non-linearizable.

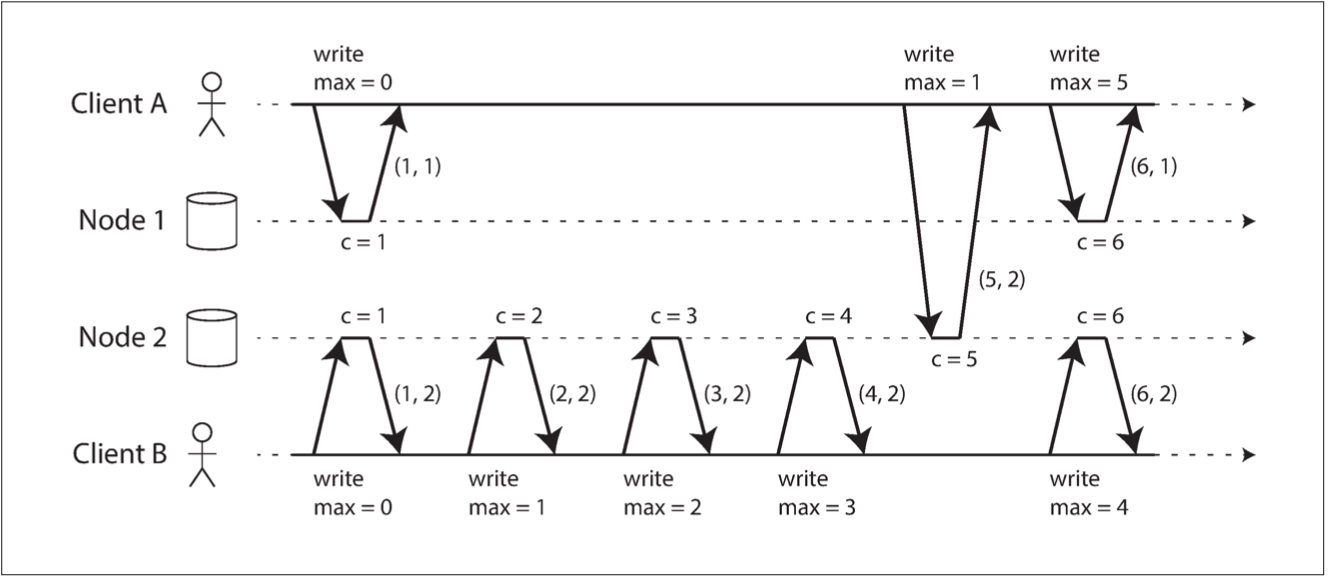

Strict quorum may fail: see image. Potential fix: sync read repair (if reader sees stale data it updates replica synchronously before sending response to the client), writer must read the latest state of a quorum of nodes before sending its writes to client.

Linearizable compare-and-set operation cannot be done in a leaderless model.

In summary, it is safest to assume that a leaderless system with Dynamo-style replication does not provide linearizability.

CAP theorem

If your application requires linearizability, and some replicas are disconnected from the other replicas due to a network problem, then some replicas cannot process requests while they are disconnected: they become unavailable

If your application does not require linearizability, then it can be written in a way that each replica can process requests independently, even if it is disconnected from other replicas (e.g., multi-leader): available but not linearizable

Misleading since network partition will happen anyway sooner or later. Better definition: either Consistent or Available when Partitioned

It only considers one consistency model (linearizability) and one kind of fault (network partitions - nodes that are alive but disconnected from each other)

Not covered: network delays, dead nodes, etc.

Linearizability === Slow

RAM on a modern multi-core CPU is not linearizable: if a thread running on one CPU core writes to a memory address, and a thread on another CPU core reads the same address shortly afterward, it is not guaranteed to read the value thevwritten value (unless fencing is used). CPU core has its own memory cache. Memory access first goes to the cache, and all changes are asynchronously written to main memory.

CAP theorem is not relevant here: within one computer we usually assume reliable communication, and we don’t expect one CPU core to be able to continue operating normally if it is disconnected. The reason for dropping linearizability is performance, not fault tolerance.

Many distributed databases choose not to provide linearizable guarantees to increase performance

Seems there is no way to make linearizability performant: Attiya and Welch prove that if you want linearizability, the response time of read and write requests is at least proportional to the uncertainty of delays in the network

Causality

If we have 2 events: A and B then possible scenarios:

- A proceeds B

- B proceeds A

- A and B are parallel

Linearizability: total order - for any two elements one is greater than another

Causality: partial order - some elements are incomparable

causal consistency is the strongest possible consistency model that does not slow down due to network delays, and remains available in the face of network failures

Sequence number ordering

time-of-day clock is unreliable, logical clock - increments with each operation

they are compact (few bytes) and provide total order

In a database with single-leader replication, the replication log defines a total order of write operations. Follower is always causally consistent.

With multi-leader or leaderless: Lamport timestamp - pair (counter, node ID). When sending a request also send the max counter seen so far (Node 1 updates to c = 6)

Lamport timestamp doesn't tell if operation subsequent or concurrent as opposed to version vectors. It's more compact though.

Lamport timestamp problem

When request for unique name is sent node doesn't know about other nodes operations. So it cannot decide if this operation was the first in total order or not until it collects data from other nodes. Which is not network fault tolerant.

To be able to declare operation safe you should have your total order finalised before sending response back to the client.

Solution: Total order broadcast (or Atomic broadcast).

Implemented by ZooKeeper and etcd.

Reliable delivery - no messages are lost: if a message is delivered to one node, it is delivered to all nodes.

Totally ordered delivery - messages are delivered to every node in the same order.

Total order broadcast

order is fixed at the time the messages are delivered: a node is not allowed to retroactively insert a message into an earlier position in the order if subsequent messages have already been delivered. This fact makes total order broadcast stronger than timestamp ordering

fencing tokens: every request is appended to the log, and all requests are numbered. Sequence number can serve as token since it monotonicaly increase (called zxid in ZooKeeper)

linearizability is not the same as total order broadcast

Total order broadcast is asynchronous: messages are guaranteed to be delivered reliably in a fixed order, but there is no guarantee about when a message will be delivered (so one recipient may lag behind the others). By contrast, linearizability is a recency guarantee: a read is guaranteed to see the latest value written.

Total order broadcast

How to implement linearizable compare-and-set operation with unique constraint using total order broadcast:

- append a message to log indicating a unique value you want to claim

- read the log and wait for message you appended to get back to you

- check if anyone else appended a claim message for the same value. If not then you can commit your claim, otherwise abort.

This doesn't make read linear, and called sequential consistency or timeline consistency. To make reads linearizable:

- append read message, read the og and make actual read after receive log including the read message (etcd works this way)

- fetch position of the latest log message, wait for messages until this position, perform read (used in ZooKeeper)

- sync update replicas on writes (used in chain replication)

Total order broadcast

How to implement total order broadcast using linearizable register with get-and-set operation:

- for every message add a sequence number from linearizable storage

- those numbers don't have gaps meaning they will always processed in sequence if if they delivered unordered due to network failure

it can be proved that a linearizable compare-and-set (or increment-and-get) register and total order broadcast are both equivalent to consensus

linearizable compare-and-set = total order broadcast = consensus

Consensus

get several nodes to agree on something

Use cases:

- leader election in single-leader replication model

- transaction atomic commit: all nodes commit a transaction or rollback it

FLP proves that consensus is not achievable in a model when we cannot rely on timeouts, meaning cannot understand when node has crashed. In practice we can make assumptions about nodes being crashed

Two-Phase commit (2PC)

Atomic commit on single node: all records go to a log which is durable. Commit record in the log means transaction is commited. Order is guaranteed by a particular hard drive on a particular node.

once a transaction has been committed on one node, it cannot be retracted again if it later turns out that it was aborted on another node => node must only commit once it is certain that all other nodes in the transaction are also going to commit

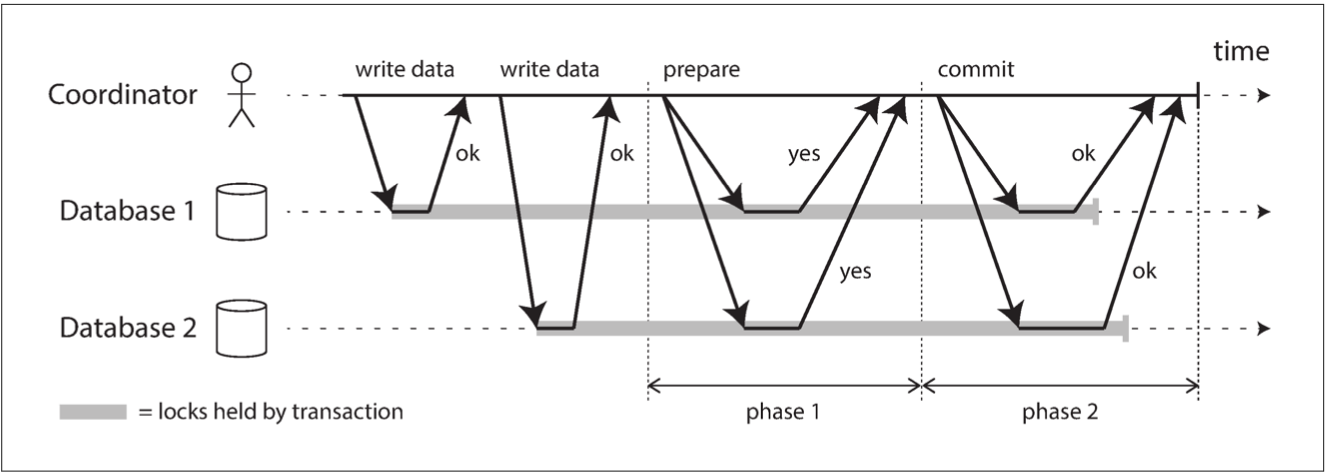

Two-Phase commit (2PC)

1. app requests a globally unique transaction ID from coordinator

2. when a participant replies positive to "prepare" message it makes sure it can definitely commit the transaction - write to disk, check for conflicts/constraints violations (this cannot be reverted)

3. when coordinator decides on a transaction result it writes it to the transaction log on disk (this also cannot be reverted)

4. if any node fails afterwards coordinator sends decision indefinitely until it's delivered

5. if coordinator crashes before sending decision then node stucks in `prepared` state

Two-Phase commit (2PC)

2PC is a blocking atomic commit protocol since it can stuck if coordinator fails

3PC solves this but it relies on the ability to ensure a node failure which is not true

Distributed Transactions

DB internal distributed transactions: VoltDB, MySQL (10x slower than single-node)

- if node fails then coordinator waits then other nodes wait which leads to failures amplification

Heterogeneous distributed transactions: multiple storages from different vendors

X/Open XA (eXtended Architecture) transactions (supported by PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server, Oracle, ActiveMQ, MSMQ, IBM MQ)

- coordinator must be highly available (replication)

- coordinator on the app node makes it stateful

Fault-Tolerant Consensus

Uniform agreement: all nodes decides the same

Integrity: ones node decided it cannot change their mind

Validity: if node decides value V, this value was proposed by some node (prevents solution when everyone decides always on for example NULL)

Termination: every node which doesn't crash decides something, in other words cannot sit and waiting for something forever - it must make progress (prevents solution of 2PC when everything is stuck if coordinator fails)

first three (safety) are satisfied even if majority of nodes fail

forth one (liveness) is satisfied only if majority is alive

Fault-Tolerant Consensus

Single leader replication without consensus algorithm to select a leader doesn't satisfy termination property since human has to select a new leader (meaning human intervention needed)

Consensus algorithms compared to 2PC:

- don't have a single coordinator but elect it whenever old coordinator fails

- make decision on proposed value not by getting all nodes to agree but based on majority

Whenever a new leader (coordinator is elected) the epoch number is changed.

When a new value is proposed coordinator sends its epoch and each node checks if they are aware of higher epoch or not.

Since both leader election and value proposition are made by majority of nodes - those two sets shall overlap.

Consensus downsides

They require sync confirmations from majority of nodes which affects performance

Increasing number of nodes often unpredictable

With unreliable network false positives of node failures detection may lead to leader/coordinator reelections and bad performance

Distributed key-value stores

ZooKeeper and etcd

another name: coordination and configuration services

- designed for small amounts of data to keep in memory (although write to disk for durability)

- data replicated among all nodes using total order broadcast

- ZooKeeper (+ Google Chubby): atomic operations like copare-and-set

- ZooKeeper (+ Google Chubby): each operation has a monotonically increasing transaction id and version number - used for fencing tokens

- ZooKeeper (+ Google Chubby): keeps track of client failures. If client doesn't respond within a timeout it's called an ephemeral node

- ZooKeeper (+ Google Chubby): client can subscribe to notifications about other nodes added/failed

- often used for service discovery tasks

Consistency and Consensus

By Michael Romanov

Consistency and Consensus

- 39