Welcome

Multimedia

Jan 29, Feb 12, 26, Mar 11 and 25th

2-8pm

Elizabeth Kilroy

This five hour multimedia immersion class meets five times every second week and provides students with the opportunity to explore combinations of audio, video and still image slideshow storytelling. This class provides hands-on training for visual journalists looking to expand and grow their multimedia skill sets using DSLRs and/or smart phones. Students learn how to plan, develop and sequence narratives for multimedia.

Visual techniques for multimedia storytelling like how to shoot in sequences, frame and compose motion and anticipate action will be addressed. Students will record and integrate audio interviews and ambient sounds and learn techniques for interviewing and putting subjects at ease. Recommendations on equipment, apps and techniques for smart phones for mobile journalism will be addressed.

Every student will produce a finished, polished project -- from capturing all the content to labeling and naming assets, to editing and compressing the final files using Adobe Premier.

Do I need a Script?

Before VHS almost all doc films were shot on 16mm, and scriptwriting was mandatory.

The high cost of the material meant that every foot had to be planned and a ratio of 6:1* was considered generous.

1. Action

2. Camera Movement

3. Sound

* A film with a shooting ratio of 2:1 would have shot twice the amount of footage that was used in the film. In real terms this means that 120 minutes of footage would have been shot to produce a film of 60 minutes in length.

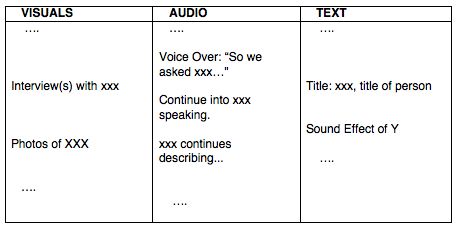

Three Column Scripts

Shooting Video

- Ratio of 30:1 is not uncommon

- Working out the final story seems often to evolve at the time of editing

- So what is required to be written before shooting begins ?

Let's Discuss Your Idea for a Documentary

- Has it got the obvious qualities of good storytelling?

- Is it a journey with a conflict and a resolution?

- Has it got a strong personal element?

- Where do you, the filmmaker stand in relation to your subject?

Goal for this class - to include

- An observational sequence or finished movie

- A core moment of truth

- A character study

- Interesting personal experiences

- One which tries to use visual language in a poetic way

What about the audience?

- Who is speaking to me?

- Is that voice credible?

- Am I being manipulated?

- "I write down themes and try to work out ways of creating dramatic structures and hopefully take the audience on an interesting journey where they have certain hopes that I might try to fulfill," says one doc film maker

- "I am always questioning identity" says another. "questioning motives."

So what do I need to write down?

- Ideas for a narrative

- Voiceover script

- Ideas for scenes

- Storyboard to think about certain shots and how they might affect the message

- "I am always questioning identity" says another. "questioning motives."

Asking Questions

What do you want people to think/feel after seeing your film?

Can you focus your idea more clearly? If so, how?

Can you express your idea in just two sentences?

Do i need to do research?

Before you go out to shoot have a list of questions

.

Priorities in judging ideas

Is it an exciting idea?

Is it realizable in the time we have - 10 weeks meeting every second week

.

Inspiration

Adapted Copy and Selected from A Taste of Cinema

1. Junkopia (1981)

Short experimental documentary by the late master Chris Marker that depicts illimitable and strange inanimate objects that are contrasted with the contemporary World. Seemingly banal things are merged together into a modulated montage; cars, freeways, ambient sounds of cities and towns. In the background of the forgotten island the film has been studying, we see a large metropolis, living its usual fast lifestyle. The small island watches the city from a distance, as if it were a ghost watching the living from limbo.

Why it’s essential?

Any Chris Marker film is essential, maybe even more so after his passing. Junkopia may not be as famous as Markers earlier film La Jetee, but holds a similar amount of significance, and broadens our horizons to questions like “what is the purpose of documentary?”

2. O Dreamland (1953)

A 1953 documentary directed by British film legend Lindsay Anderson and his cameraman/assistant, John Fletcher. Shot on a single 16mm camera and a cheap audiotape recorder, the film marked a new generation of British filmmakers.

Anderson didn’t use the footage for a while, not until he attached it with the first Free Cinema movement programme. Free Cinema (for those who do not know) was a documentary movement that eventually lead the launch of the British New Wave.

Shot in black-and-white, the film shows us an exploration of a funfair park called Dreamland in Kent, UK. At the time its replacement of narration commentary with background noises and music, was quite unusual in the British documentary scene (Something not done properly since Mr. Jennings himself).

One of Free Cinema’s key supporters Gavin Lambert said, “Everything is ugly… It is almost too much. The nightmare is redeemed by the point of view, which, for all the unsparing candid camerawork and the harsh, inelegant photography, is emphatically humane. Pity, sadness, even poetry is infused into this drearily tawdry, aimlessly hungry world.”

Why it’s essential?

One of the most influential and significant films of the free cinema movement in Britain, even if you do not appreciate it as a piece of film, its historical importance is undeniable.

3. Talking Heads (1980)

Polish film legend Krzysztof Kieslowski interviewed people from different ages, professions and social statuses, asking them all two questions.

1 Who they are?

2. What they want from life?

The interviews are edited together in age order, starting from youngest to oldest. We slowly see the gradual changes in the human mind set, how our views of self and purpose, no matter what class we are from, changes during maturity.

Why it’s essential?

One of the most influential short documentaries available for public viewing, proving a documentary can still be intense and incisive even with a simplistic format. The film’s technique has been replicated by short documentary filmmakers for years after, even to the extent of it being remade in 2009 by documentarian Gabe Van Lelyveld.

It also holds a historical significance, being a massive milestone in the late, great Krzysztof Kieslowski’s career.

4. Listen to Britain (1942)

No narration or interviews, just images and sounds of wartime Britain edited together like a cinematic orchestra.

Influential filmmaker Humphrey Jennings was known for his more ambiguous and poet approaches towards war time propaganda documentary. Listen to Britain gives us an unorthodox insight into Britain during WWII. Shot in 1942, the short film masterfully selects the small details of ordinary people’s lives to produce an affecting and rhythmic portrait.

Why it’s essential?

Listen to Britain is undoubtedly one of the most lyrical documentaries ever made, but it was also one of the main inspirations for Britain’s Free Cinema movement in the 1950s, which would later evolve into the British New Wave.

5. The Quiet Mutiny (1970)

John Pilger’s iconic film debut The Quiet Mutiny was filmed at Camp Snuffy in 1970 and produces a character study of several soldiers during the Vietnam War. For the first time it revealed the unstable confidence among the Western troops and how it lead eventually led to mutiny.

The film analyses each character beautifully, never making direct political statements. It purely relies on the characters frame of mind and morale to shape its criticisms on the war.

Combining interviews with frontline footage of Vietnam, it portrays the developing fractures between the US military officials and the soldiers who were physically fighting the war on the ground.

Why it’s essential?

It completely changed the public-media perception of the Vietnam War and contributed significantly to the US troops withdrawing.

6. The Train Stop (2001)

In this 24 minute magnum opus we travel to a small, isolated train station deep within rural Russia at night. The camera never leaves the room, but we hear the faint sounds of the clattering locomotives and harsh weather conditions outside. The tiny wooden station is bounded by snow and inside, everyone is asleep. The camera slowly glides over the sleeping commuters; each person is in a different posture or position. The vibrant sound of the people snoring contrasts with the stillness of the visuals, creating an eerie and surreal tone. It is almost as if time continues to go on outside, but inside the train station time is frozen at a halt.

Why it’s essential?

According to the director Sergei Loznitsa, the film is a metaphor for the contemporary Russian people’s ‘falling out of time’ mentality.

Metaphor or not, it shows us that documentary isn’t just a tool to inform us about data and worldly problems; it can also be just as effective as drama in illustrating an atmosphere

7. A Valparaíso (1962)

I'm sure when I tell you this film is a travelogue of Valparaiso in Chile, you would disregard it straight away. If you were to give it a chance however, you would see that it is one of the most beautifully depicted journeys ever captured on celluloid.

It is a geographic illustration of everyday occurrences of Valparaiso, contrasted with more concerning issues, like the poor residents struggling to obtain sufficient amounts of water supplies. It is not all doom and gloom though; the film depicts the more vibrant activities, like members of the community dancing, circuses, a race course and children feeding sealions at the harbour.

The film’s second half takes a drastically different direction, highlighting the towns disturbing pirate past. The two halves set up a captivating contrast, which puts into account the role our history plays in defining who we are now.

Why it’s essential?

Without a shadow of a doubt, A Valparaiso is one of the most profound poetic documentaries out there.

8. Black Breakfast (2008)

‘Black Breakfast’ is a peculiarly pessimistic look at the alleged Chinese government’s disregard of its people’s health and safety, whilst executing industrial operations.

There are no interviews or narration; it just follows a tourist in China looking to find hidden archaeological treasures. The woman finds herself at odds with the local pollution caused by the industrial waste. The film was created to champion global human rights and was part of a bigger project to support the cause.

The film is a simple montage, but holds so much power and beauty that it surpasses its minimal narrative.

Why it’s essential?

Directed by Jia Zhangke, who is known for highlighting important social issues in mainland China in the most faint and graceful ways.

9. The Forgotten Faces (1961)

The Forgotten Faces is a docu-drama reconstruction of the Hungarian revolution in 1956. Director Peter Watkins (Punishment Park and The War Game) develops his methods of naturalistic reconstruction that he attempted in his previous short films. Using techniques you would find in French New Wave and Italian neo-realist films; like non-professional actors, on-location settings and filmed with natural lighting.

Watkins said:

“Most of my feelings about this kind of what I would call documentary or reconstruction of reality came from studying photographs. I think that’s where my feelings about grain and people looking into the camera came from … especially those very strong photographs taken in the streets of Budapest and published in Paris Match and Life. That was my first in-depth encounter with an actual situation …”

Why it’s essential?

The master of the docu-drama, Peter Watkins is an essential filmmaker for any film fan to sink their teeth into and this short gem is a solid example of the man’s undeniable genius.

10. Stonebridge Park (1981)

Over the years, British filmmaker Patrick Keiller has developed his own distinctive style of documentary and during the 1990’s revolutionised the film essay.

Stonebridge Park is separated into two parts. The first part, the narrator (who is never seen, the film is viewed from his perspective only) contemplates robbing his former boss and describes the events that lead him to consider such an act. As the narration goes on the camera roams around the nearby road junction, where the protagonist is waiting to make his move. The second part is set after the man has burgled his former boss, where he is now panicked and reflecting on what he had done moments ago.

Why it’s essential?

An incredible mix of documentary essay and narrative, any Patrick Keiller film is essential for anyone interested in alternative documentaries.

StonebridgePark by zohilof

11. Journey on the Plain (1995)

Journey on the Plain is not the first Bela Tarr documentary, but could certainly been seen as his best. It is the epitome of a documentary poem, and is made up solely of Mihály Víg reciting the poetry whilst travelling round a plain. Víg recites the poems of Sándor Petöfi, a nineteenth century Hungarian poet who was a key member of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution.

Why it’s essential?

For fans of Bela Tarr this is a must see and even if you are not, this is an incredibly hypnotic and stylistically important documentary.

Unlike Tarr’s work from 1990 up, the film is shot on digital and in colour, seeing his mesmerizing long takes and magnetic soundtrack in a format other than black and white, is worth the watch alone.

12. Momma Don’t Allow (1956)

Typical of a Free Cinema film, Momma Don’t Allow was shot on 16mm film, but untypical, was its warmer and more sympathetic tone to its working-class subjects. It captured the then rising ‘teenage culture’ and contrasted the ‘Teddy Boys’ (relaxed cool working class) with the more middle class/self-conscious ‘Toffs’.

The 1950s British Jazz scene was caught beautifully, and the film almost integrates the scene’s ‘liberated’ attitude into the filmmaking process itself.

The documentary was shot by British New Wave marvel Walter Lassally and you can see the early developing characteristics in his photography that would later make his name.

Why it’s essential?

Not only a great short documentary, but it’s fascinating seeing the soon to be legendary filmmakers Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson’s launch pad film.

13. Night Mail (1936)

At the time, Night Mail was the most critically acclaimed British Documentary film, and was also one of the most commercially prosperous. The film was primarily made to promote the post office services during the war, but at the same time experimented with groundbreaking uses of sound, narrative and editing.

It accounts the procedures of the Royal Mail train delivery service, showing sequences that depict various operations and measures. But don’t let this put you off; this documentary is a visual and audio feast, with some exhilarating, before its time techniques that makes it both interesting and entertaining.

Why it’s essential?

One of the best known and influential films of the British Documentary movement and is even narrated by John Grierson, who many consider to be the father of British and Canadian documentary.

14. Les Mains Negatives (1978)

Directly translated as ‘’Negative hands’, the whole film is from the perspective of a slow journey through Paris at 7 in the morning and wonderfully captures the city’s desolate post-night life.

Directed in 1979 by the French writer and filmmaker Marguerite Duras and consists modestly of a sequence of images and a voiceover. The narration is read by Duras herself from a separate script she published prior. The images are actually out-takes from her previous film Le Navire night, and the script was written around the unused footage. In a sense, Duras created a monologue as an interpretation of the reedited footage, almost like the film version of a psychologist’s ink blot test.

Why it’s essential?

Everything Marguerite Duras made is essential, be it film or literate.

les mains négatives, (margueritte duras) by zohilof

15. The Alaskan Eskimo (1953)

The Alaskan Eskimo is a beautifully crafted depiction of the Alaskan Inuit communities in 1953. Originally produced by none other than Walt Disney, as a way of educating young people about the various cultures and places around the world that many at the time, would have had no idea existed.

Have you ever seen Disney do documentary? If not, you will be surprised, they feel like a typical Disney production in the sense everything is fantasised and even the animals are given spirit personas/stories.

Why it’s essential?

The film won an Oscar at the 26th Academy Awards in 1954 for Documentary Short Subject. Unfortunately the film is not currently available on DVD or Blu-Ray, so make sure you take full advantage of this often overlooked Disney masterpiece.

16. Women’s Quarter (1966)

Depicting the everyday life of prostitutes in Tehran’s red light district in the 1960s, the film intimately follows several women and probes into the frantic conditions that directed them into their profession. Controversial at the time, the film was banned before its production was finished and some of the original footage was lost. Despite all of these obstacles and set-backs, the director (Kamran Shirdel) still went onto complete the film just after the 1979 Iranian revolution. Using the late Kaveh Golestan’s photographs (an important Iranian photojournalist and artist) that were taken more than a decade after the original footage was shot.

Why it’s essential?

An elegiac, yet disturbing insight into the treatment of prostitutes in an Iran that is so different to the one we know of today. Also it is a fine example of Iran’s most prominent documentary filmmaker.

17. Churchill’s Island (1941)

Using a mix of newsreel, official British government and detained German government film footage, Churchill’s Island is a WWII propaganda film about Britain’s fight against Germany. The film begins with Britain and Germany fighting in an air war in 1940, then to the ship battles in the Atlantic and finally, all the way to England where the Brits are preparing for a sea invasion on the southern coasts.

The documentary soon reveals its true purpose when the narrator informs us that with the help of America and Canada, England will not be defeated by Germany.

Why it’s essential?

It was the very first film to win an Academy Award for a Documentary Short Subject and the first National Film Board of Canada (NFB) film to win an Oscar.

It is also a good historical record of the many attempts made to get the USA and Canada to join Britain in the rapidly developing WWII.

18. Ten Minutes Older (1978)

Although Herz Frank’s short film Ten Minutes Older has to be seen on the big screen, it is still effective even when watched on a smaller one. The film captures the faces of an auditorium full of children as they watch a show we never properly see. We are only allowed to view the children reacting in different ways, with different emotions and never once does it get tiresome.

Why it’s essential?

A fascinating and moving experiment, it will open your eyes to the emotional power of adolescent innocence and curiosity. The fact it is essentially a post-modern meta-documentary, a film showing us the reactions of children watching another film, helps us re-evaluate and appreciate the influence cinema actually has.

Critic and filmmaker Mark Cousins called Ten Minutes Older one of the greatest films ever made and clearly had an influence on his own film – A story of children and film.

19. Luv’in the Black Country (2010)

This 10 minute doc-drama is based around the first love testimonials of three old people who pass by a neglected industrial canal line. Shot in black and white, the film explores the gentle canals and abandoned factories that reside in a heavily industrialised region of Britain called, the Black Country. Three local residents share stories of their first loves and nestled within their recollections is heartbreak and frustration. The fall of the local industry resulted in many of the local people losing their identity and sense of purpose.

Why it’s essential?

A quiet, yet passionate protest film about the effects Margaret Thatcher’s privatisation had on small industrial regions of the UK. Without the use of narration (apart from an old archive clip at the start and end), direct reference to politics or manipulative music, the documentary ironically uses the positive theme of love to show the bitter-sweet deterioration of a cultural identity.

20. Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895)

A black-and-white silent documentary directed and produced in 1895 by the celebrated Louis Lumière. The film consists of one continuous sequence where workers leave the Lumière factory, consisting mainly of women who look as if they had just finished a hard day’s work.

The film at one point was considered to be the first film ever made, whether this is true or not (which is isn’t, the 1888 film ‘Roundhay Garden Scene’ by Louis Le Prince takes this cookie) it is still the first film to consciously attempt refined composition, and to focus properly on the direction of its mise-en-scene.

Why it’s essential?

You can’t talk about essential documentaries, or any type of film for that matter, without mentioning at least one Lumière Brothers picture. It’s pretty much in the rules!

If you do not see any worth in its artistic importance, then surely you have to appreciate its general historical value. Yes, yes, it may only be people walking out of a factory, but seeing film in its infancy and people from a time so far from us now, is enthralling, right?

"I talk a lot about the role of the researcher and his relationship with the individual—how you portray an individual in terms of autobiography?

Quite a few students, because they start research on the Internet, tend to get entranced by issue, rather than personality. So, for instance, currently I've got students researching transvestites, and the danger is that they will make a documentary about transvestitism, as opposed to the study of an individual person.

They need to become perceptive about how an audience will see an individual once he is on screen, as opposed to being immediately in front of them. It becomes a group writing exercise, and I encourage them to put down their work in the form of a treatment. " - Peter Hort

Getting Started

- plan out the story, which means, above all, knowing what questions to ask

- active question - raise an issue that the audience wants to have an answer to.

- find a subject that creates a sense of narrative interest leading to some sort of revelation at the end

- It can also be something that comes to life during editing because you don't always get the footage you expect

- the doc script is a two-stage process: pre-production and post-production—both very important

Treatment

While a script may not be necessary, you do need to be able to describe your film vividly in treatment form—

A budget

a note on the filmmaker's experience,

an argument for the importance of the project

why you are going to film

a table of contents

documentation showing you can get access to the locations

a title sheet

additional material

a single-page presentation and a covering letter.

deck

By nmn_slides

deck

Multimedia one

- 165