Costly Belief Elicitation

| Brandon Williams |

Alistair Wilson |

| ASSA Beliefs Session January 2025 |

An experimental testbed for understanding effort and incentive in belief elicitation

Intro/ Basic Idea

- Experimental economists commonly give incentives when we elicit beliefs. Why?

- Hope that by providing incentives we collect better, more-accurate beliefs:

- Understanding what is asked requires effort

- Overcome personal motives to distort

- Doing burdensome calculations

- Therefore, if belief elicitation is an effortful exercise, how do we best increase the precision of the expressed belief?

Want to understand what incentives produce honest, deliberative beliefs

Motivation

0

100

20

80

Want to understand what incentives produce honest, deliberative beliefs

Motivation

0

100

20

80

Project Roadmap

- Create a task that mirrors forming a probabilistic belief that requires effort

- Use experiments on Prolific to understand the relationship between cost, effort, and output

- Vary the task primitives and measure how long it takes to complete (effort), willingness to accept (cost) and accuracy (output)

- Understand how hard this task is to guess (zero effort output)

- Then use the task with different incentives

- To do: Measure the psychological costs for forming objective Bayesian posteriors

Literature

Some examples of recent papers in belief elicitation:

-

Testing incentive compatibility:

- Danz, Vesterlund, and Wilson, 2022

- Healy and Kagel, 2023

-

"Close enough" payments:

- Enke, Graeber, Oprea, and Young, 2024

- Ba, Bohren, and Imas, 2024

- Settele, 2022

-

QSR or BSR:

- Hoffman and Burks, 2020

- Radzevick and Moore, 2010

- Harrison et al., 2022

-

Others (exact or quartile):

- Huffman, Raymond, and Shvets, 2022

- Bullock, Gerber, Hill, and Huber, 2015

- Prior, Sood, and Khanna, 2015

- Peterson and Iyengar, 2020

Treatments

So far we have the following treatments:

- A calibration treatment where we measure how long it takes to complete the problem (Effort); and how accurate you are (Output), then elicit your willingness to accept payment for the task (Cost)

- An initial guess treatment where we measure your first instinct (low-effort output)

- Incentives treatments where we change the reward structure (horserace across incentives)

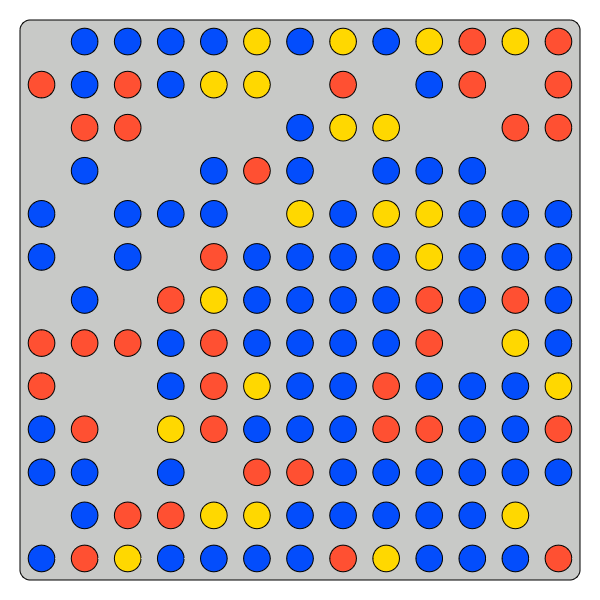

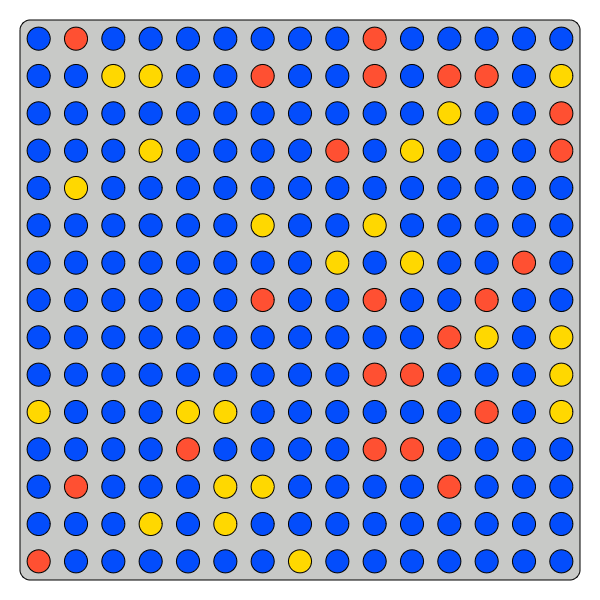

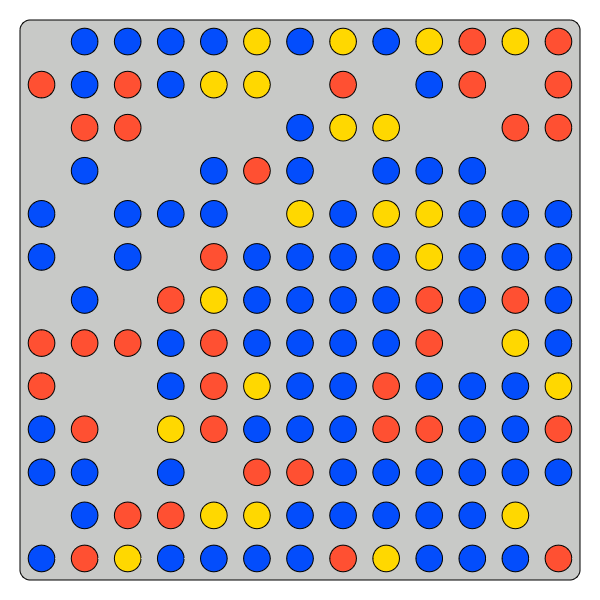

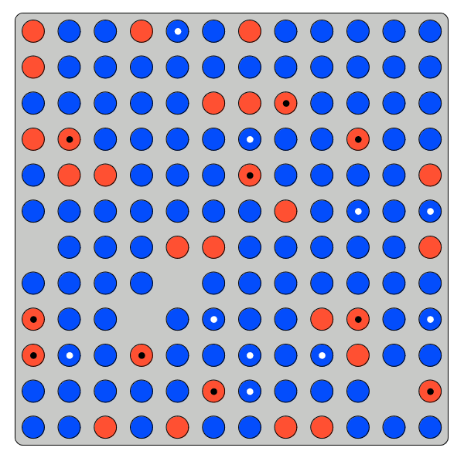

Basic Task

- Create a task that mirrors forming a probabilistic belief that requires effort

- What is the proportion of blue tokens in this urn?

Ans: 56.25%

- Create a task that mirrors forming a probabilistic belief that requires effort

- Use experiments on Prolific to understand the relationship between cost, effort, and precision

- Vary the cost for precision and calibrate on how long it takes to complete and willingness to accept (calibration treatment)

- Understand how hard this problem is to guess (initial guess treatment)

- Vary the reward structure:

- BSR with no information

- BRR with qualitative information

- BSR with quantitative information

- A "close enough" incentive

Experimental task

How to get you to exert effort when formulating your belief?

We start by paying $0.50 if you exactly count:

- Number of blue tokens

- Number of total tokens

Measure accuracy and time taken

Vary the difficulty over 5 tasks

Calibration: Training

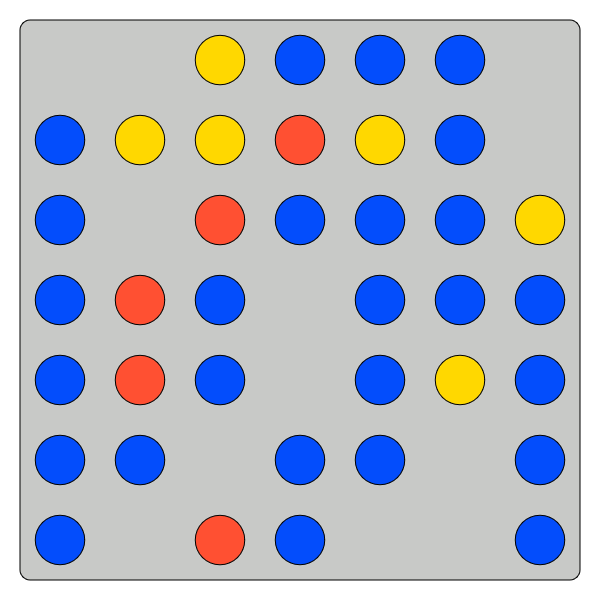

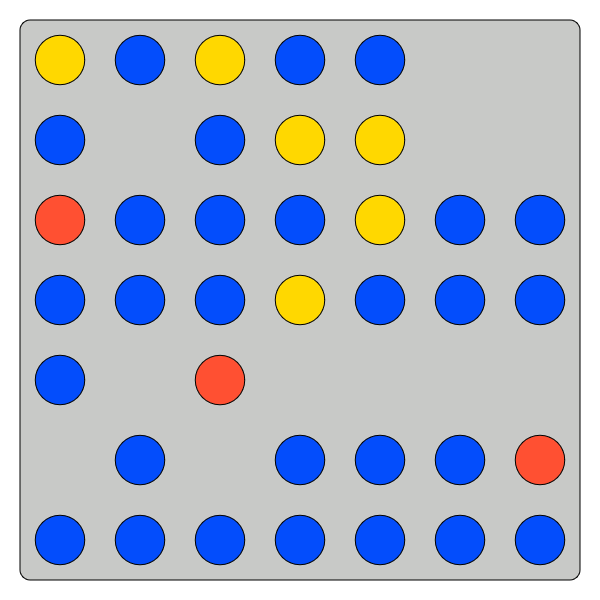

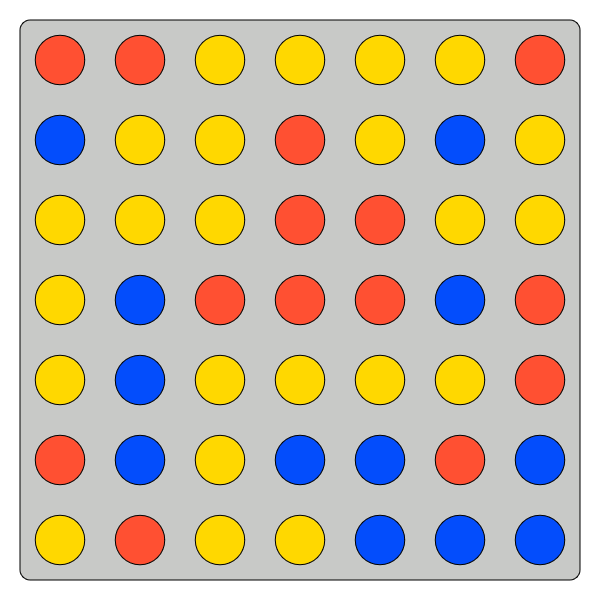

Task Variance

Small no gaps

Small gaps

Larger no gaps

Larger gaps

Task Variance

Each problem characterized by a tuple \(\left(N,\theta^\star,\delta_\text{Gaps}\right) \):

- \(N\): total number of tokens in urn

- \(\theta^\star\) the true proportion of blue tokens

- \(\delta_{\text{Gaps}}\): indicator for gaps

\(\left(N,\theta^\star,\delta_\text{Gaps}\right) = (139 , \tfrac{81}{139},1) \)

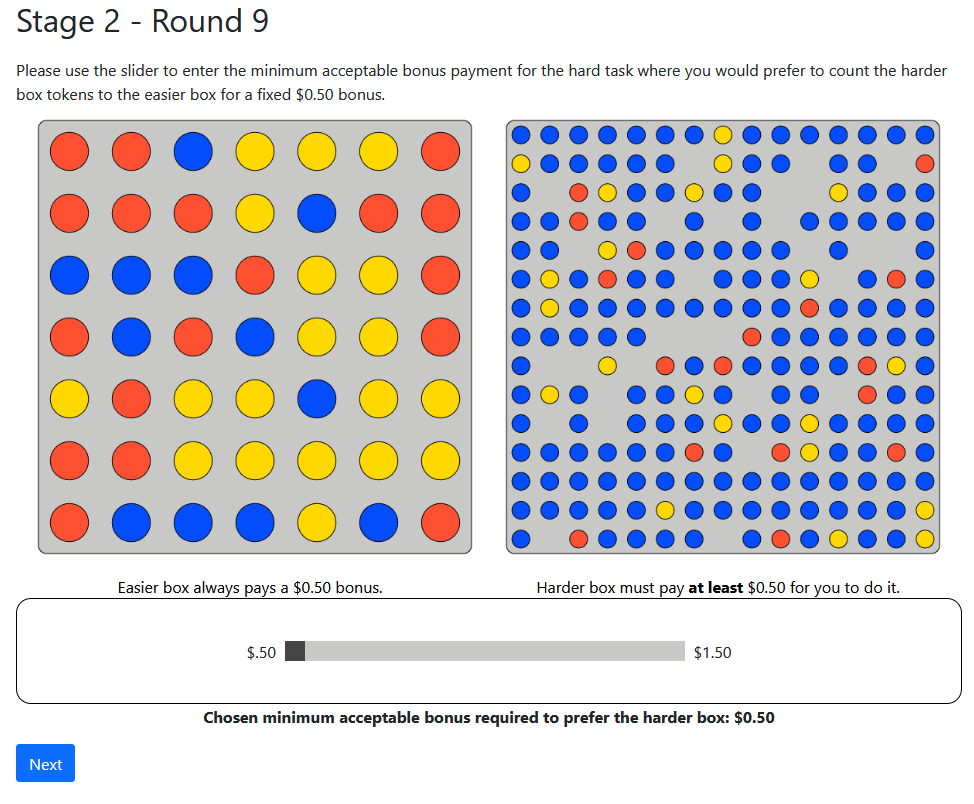

Willingness to Pay: Oprea (2020)

Ten rounds: An easy task, or a Hard one plus amount \(\$X\)

LHS:

Constant

Difficulty

RHS:

Varying

Difficulty

Always

Pays $.50

If Correct

$X

If Correct

Choose

$X threshold

Calibration Results (\(N=250\))

From models over \(\left(N,\log(N),\delta_\text{Gaps}\right) \)

Effort (time spent)

Cost (WTA)

Output (within 1%)

\(\text{OLS }\log(\text{Effort})\)

\(\text{Tobit}(\text{WTA})\)

\(\text{Logit}(\text{Within 1\%})\)

Initial Guesses

Need to get a sense for how hard this problem is to guess.

- Give them 15 or 45 seconds to form and enter a guess on the proportion

- Higher powered rewards:

- $2.50 if within 1%

- $1.00 if within 5%

- $0.50 if within 10%

- Ask them about 10 proportions (pay three decisions)

Initial Guess Results (\(N=200\))

After 15 second

After 45 second

Task Conclusions

- So we have an experimental task that:

- We can scale the difficulty

- Where we understand the broad costs and efforts required to succeed

- Where we understand the output level at low-effort

Incentives

Use four incentives to ask about beliefs in ten different urns:

-

BSR-Desc: $1.50 prizewith only qualitative information on the details

- Text description of payoff structure (Vespa & Wilson, 2018)

-

BSR-Inf: as above but with quantitative information

- Full information on the quantitative incentives (Danz et al., 2022)

- BSR-NoInf: only know there is a $1.50 prize, no other information on the incentives

- A "close enough" incentive

- $1.50 if within 1%; $0.50 if within 5%

- Current use in several papers (e.g. Ba et al., 2024)

- Pay three of the rounds

- \(N=100\) each incentive treatment

- No time limit

Model

- Agents know that there are \(N\) tokens in the urn, but are unsure about the blue proportion

- Initial prior on the number of blue tokens is \[\text{BetaBinomial}(1,1,N)\]

- Can choose to sample \(0 \leq n \leq N \) tokens without replacement from the urn (Hyper geometric signal)

- Counting \(k\) blue balls and \(n-k\) non-blue leads to posterior \[\text{BetaBinomial}(1+k,1+n-k,N-n)\]

- With this model we can calculate the expected return from counting \(n\) balls from \(N\) under a mechanism that incentivizes a report \(q\) with payment \(\phi(q)\)

Incentives to Exert Effort

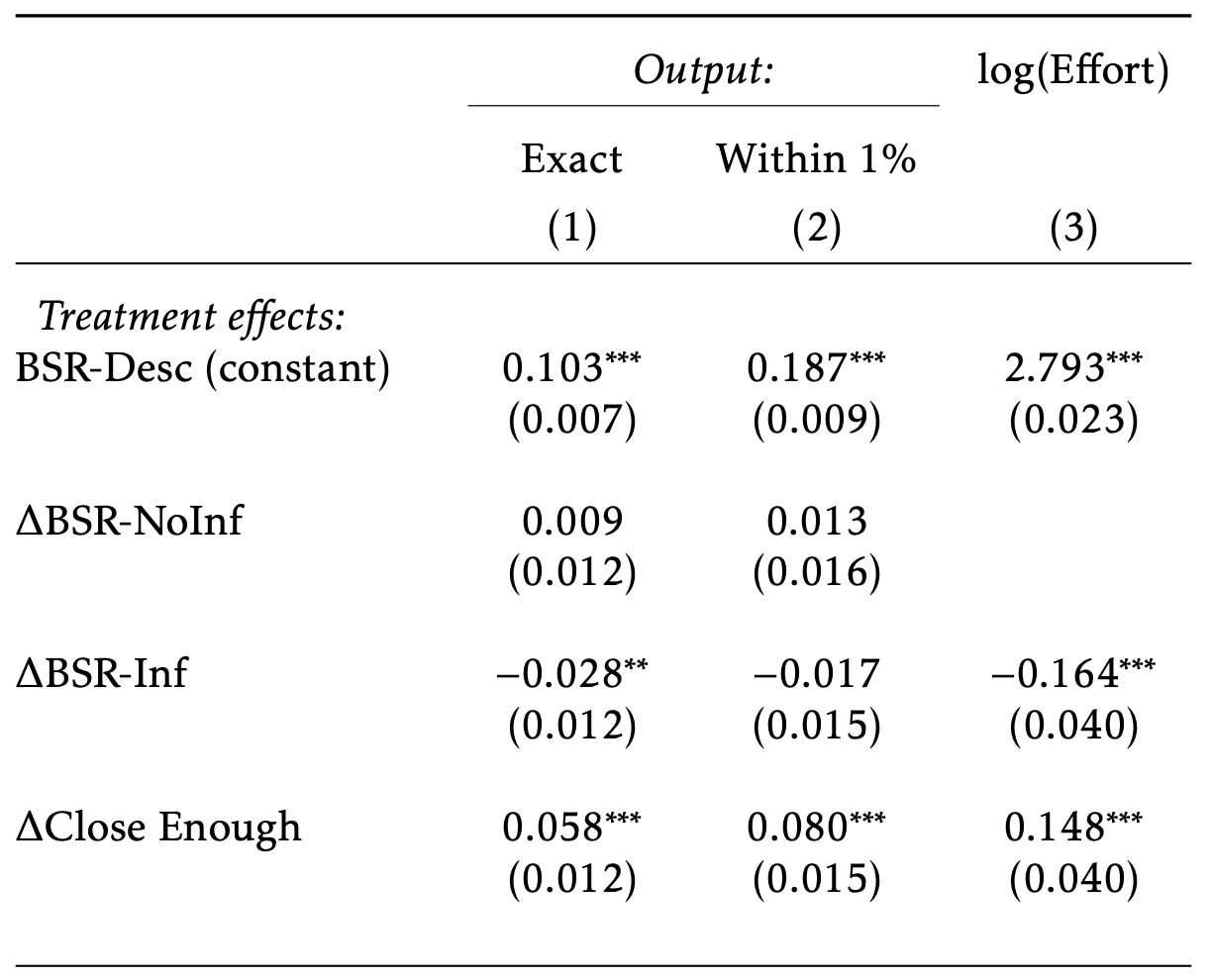

Results

Output by difficulty

Using our calibration treatments to construct instruments for difficulty:

Effort by difficulty

Using our calibration treatments to construct instruments for difficulty:

Output: Accuracy

-15%

+16%

+56%

+43%

Effort compared to Calibration

Aside: Cognitive Uncertainty

Common self-reported measure, which here we validate against effort and output in BSR-NoInf treatment...

Incentive effects

- "Close enough" outperforms BSR on both accuracy and time spent

- The better incentive effects stemming from a richer outcome space

- Also cheaper for the experimenter, payments to participants reduced by ~50% over BSR

- With a fixed budget, how much more effort could be induced?

- (But the gains here are dwarfed by the gains when we explicitly tell them what to do)

Incentive effects

Conclusions (so far...)

- Have a well-behaved task, which scales in cost/effort/output

- Close enough incentive works best well for inducing effort

- Varying the incentives:

- For BSR, no substantive differences

- Close enough produces substantial increase in effort/output; mirrors the theoretical predictions

- Still, offering incentives and letting them choose effort is swamped by authority of telling them what to do

To do:

- Examine and measure the effective costs for Bayesian updating elicitations in experiments

Bayesian Updating

Participants told:

- Number of tokens

- Proportion blue

- Proportion Dots | Blue

- Proportion Dots | Red

Are then asked for the proportion of blue balls given a dot:

- Calculation identical to standard Bayesian updating experiments

- But can also just count...

After gaining experience will ask WTP against standard counting task

CostlyBelief-ASSA

By Alistair Wilson

CostlyBelief-ASSA

- 117