Reverse Engineering

Fundamentals of Computer Security - Independent Study

Aneesh Dogra

IIIT Delhi

2013014

- What is Reverse Engineering?

- x86 Assembly

- Registers

- Flags

- Stack

- Hello world in assembly

- Disassembly

- Examples including printf and scanf

- Reversing a real binary with an authentication system

- Android

- Android Packers

- Common packing techniques

- Decompiling android applications

- LIAPP

What is RE?

- Its the process of taking an application, process, network traffic or anything you can observe about a computer system and figure out how the computer system works without having any access to the documentation, source code etc.

- Its very important in the security industry, for example anti virus companies use reverse engineering to understand malware and then developing protection mechanisms against it.

Motivation!

Reversing is a vital skill to have when you want to understand what a program is actually doing, and when you don't have access to its source code.

Intro to the CPU

- The CPU reads the machine code a program consists of and executes it.

- Machine code is just an encoding of instructions that can be understood by the CPU.

Execute

x86 Assembly

- Assembly language is a low level language in which there is a very strong correspondence between the language and the machine code.

- Each assembly language is specific to a particular architecture.

Some terms:

- Instruction Set: the complete set of all the instructions in machine code that can be recognized and executed by a central processing unit.

- Opcodes: In computing, an opcode (abbreviated from operation code) is the portion of a machine language instruction that specifies the operation to be performed. Beside the opcode itself, instructions usually specify the data they will process, in form of operands.

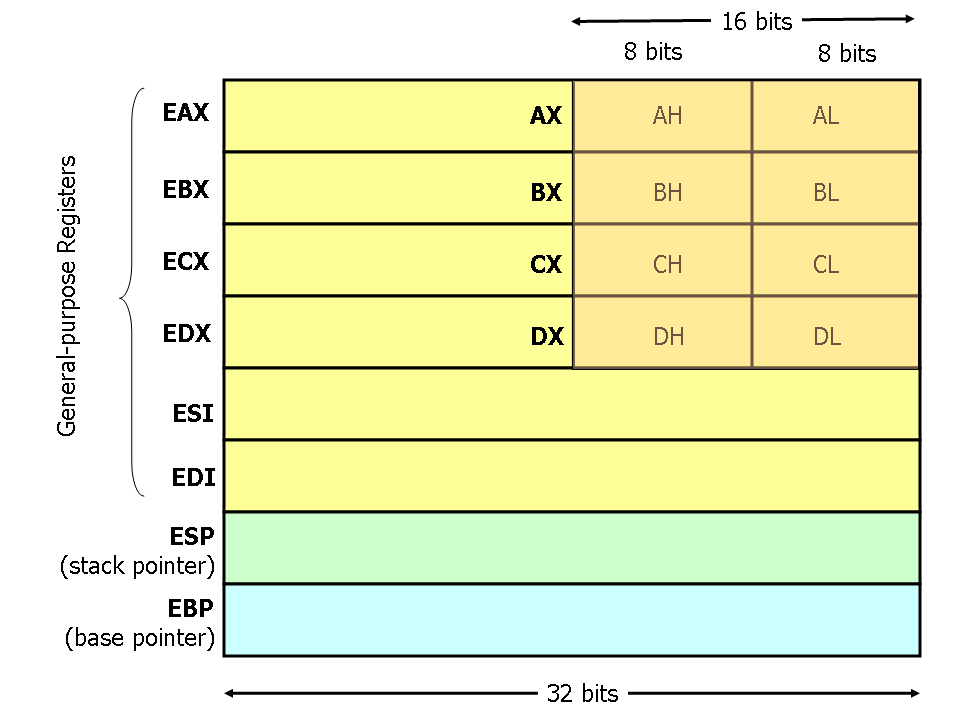

- Registers: A special, high-speed storage area within the CPU. All data must be represented in a register before it can be processed.

More about x86

Assembly is a very low level language, so its somewhat different from the languages we all use everyday to write software.

- Each instruction is represented by a mnemonic.

- ^ translates to opcodes, understandable by the CPU.

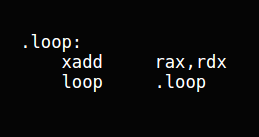

- In assembly we use registers and stack to store data.

- Addressing and memory segmentation. (Address = <segment> + <offset>)

Registers

If EAX = 0x12345678? What is the value of AX, AH, AL?

Flags

The FLAGS register is the status register in Intel x86 microprocessors that contains the current state of the processor.

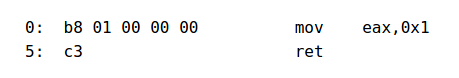

A simple function

int function()

{

return 1;

};function:

mov eax, 1

retMACHINE CODE

We took an example of a simple function that returns 1 every time.

The function boils down to 2 lines of assembly and 6 bytes of opcode

Understanding Assembly

function:

mov eax, 1

retThe first line is a label. Which suggests that we are starting a block definition in assembly.

The second line is a mov instruction it moves 1 into the eax register.

The third line returns from the function. Similar to return in C.

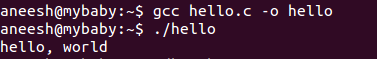

Hello World!

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("hello, world\n");

return 0;

}Lets try to disassemble the program using GDB. GDB is a GNU Debugger that can transform machine code to readable assembly code very easily.

continued..

Dissassembly

Techniques for attempting to convert the raw machine code of an executable file into equivalent code in assembly language and the high-level languages C and C++

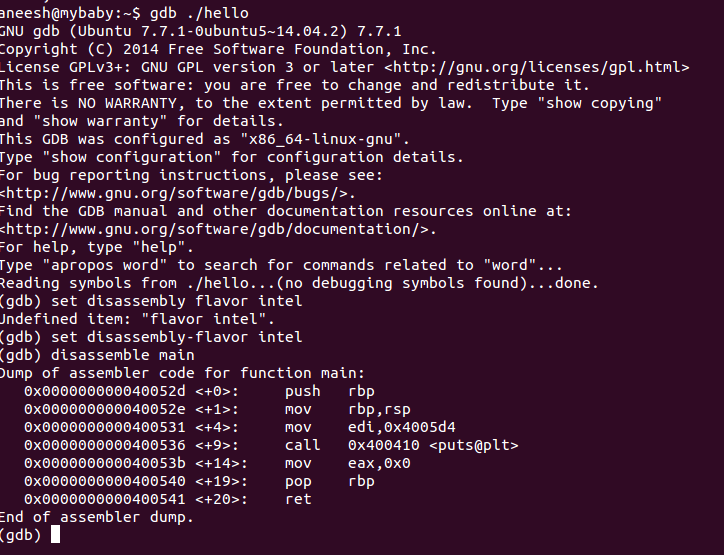

Understanding Dissassembly

(gdb) disassemble main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x000000000040052d <+0>: push rbp

0x000000000040052e <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x0000000000400531 <+4>: mov edi,0x4005d4

0x0000000000400536 <+9>: call 0x400410 <puts@plt>

0x000000000040053b <+14>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000000000400540 <+19>: pop rbp

0x0000000000400541 <+20>: ret

End of assembler dump.

Firstly, we push the old base pointer on the stack. Then we replace the base pointer with the current stack pointer.

We push some address to edi and call puts.

Then we reset the rbp and return.

Examining memory at 0x4005d4

Stack

- ESP and EBP registers are mainly used to deal with the stack in X86 Assembly.

- ESP is a register that holds the top address of the stack.

- The stack grows downward so when you push an entry to the stack the ESP gets decremented by the size of that entry.

- EBP is the base pointer register. Its usually set to ESP at the start of the function. After you push and pop things from the stack ESP is changed but the EBP is not.

- EBP is used as a reference so as to access the local variables of the function.

Stack is a very crucial data structure in assembly its used to store local variables, pass variables to a function, store return addresses of a function and more.

Stack instructions

- POP: retrieve the data from memory pointed by ESP, loads it into the instruction operand (often a register) and then add 4 to the stack pointer

- PUSH: subtracts from ESP and then writes the contents of its sole operand to the memory address pointed by ESP.

The most frequently used stack access instructions are PUSH and POP

Functions!

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, XThe function definition usually begins with:

- We push a copy of ebp on the stack so that we don't lose it. Then we update the EBP with the current ESP and subtract X number of bytes from ESP.

- Can someone guess what X is?

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

ret 0The function definition usually ends with:

- We reset ESP with the current function's EBP and then store the topmost value of ESP into EBP.

Passing args to functions

Arguments to functions are passed via the stack.

Caller:

push arg3

push arg2

push arg1

call function

add esp, 12 ; 4*3=12Callee:

| Address | Argument |

|---|---|

| ESP | address |

| ESP+4 | arg1 |

| ESP+8 | arg2 |

| ESP+0xC | arg3 |

Passing args to Printf!

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("a=%d; b=%d; c=%d", 1, 2, 3);

return 0;

}main proc near

var_10 = dword ptr -10h

var_C = dword ptr -0Ch

var_8 = dword ptr -8

var_4 = dword ptr -4

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

and esp, 0FFFFFFF0h

sub esp, 10h

mov eax, offset aADBDCD ; "a=%d; b=%d; c=%d"

mov [esp+10h+var_4], 3

mov [esp+10h+var_8], 2

mov [esp+10h+var_C], 1

mov [esp+10h+var_10], eax

call _printf

mov eax, 0

leave

retn

main endpLets compile the C program in gcc and see what we get in IDA.

what does esp & 0xFFFFFFF0 do?

"x86 processors are designed to load code and data more quickly from even doubleword addresses."

Using scanf

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int x;

printf ("Enter X:\n");

scanf ("%d", &x);

printf ("You entered %d...\n", x);

return 0;

};main proc near

var_20 = dword ptr -20h

var_1C = dword ptr -1Ch

var_4 = dword ptr -4

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

and esp, 0FFFFFFF0h

sub esp, 20h

mov [esp+20h+var_20], offset aEnterX ; "Enter X:"

call _puts

mov eax, offset aD ; "%d"

lea edx, [esp+20h+var_4]

mov [esp+20h+var_1C], edx

mov [esp+20h+var_20], eax

call ___isoc99_scanf

mov edx, [esp+20h+var_4]

mov eax, offset aYouEnteredD___ ; "You entered %d...\n"

mov [esp+20h+var_1C], edx

mov [esp+20h+var_20], eax

call _printf

mov eax, 0

leave

retn

main endpLets compile the C program in gcc and see what we get in IDA.

LEA == &

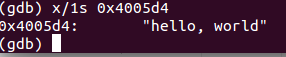

Reversing a CrackMe!

We'll try to reverse engineer a very easy crackme, crackmes are programs written by people as challenges, to help learn reverse engineering.

They're usually authentication systems we need to break to get the success message by reverse engineering the code.

Getting file information

To start reverse engineering the file we must know what type it is. Easiest way to do this is using the file command on ubuntu.

>> file crackme

>> crackmecpp: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.26, BuildID[sha1]=901287c7af167a087acdd19e0bc0087c2a993481, not stripped

GDB

Let's open the file in GDB and get the disassembly.

>> gdb crackme

(gdb) > set disassembly-flavor intel

(gdb) > disassemble main

Usually main is a opening function of most programs, if main doesn't work we can try looking at the symbol table for functions.

Disassembly

0x0804876c <+0>: push ebp

0x0804876d <+1>: mov ebp,esp

0x0804876f <+3>: and esp,0xfffffff0; alignment

0x08048772 <+6>: sub esp,0x20; reserve 0x20 bytes for storage (local variables)

; function call 1

0x08048775 <+9>: mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],0x80488c0

0x0804877d <+17>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8049be0

0x08048784 <+24>: call 0x8048640 <_ZStlsISt11char_traitsIcEERSt13basic_ostreamIcT_ES5_PKc@plt>

; function call 2

0x08048789 <+29>: lea eax,[esp+0x1c]

0x0804878d <+33>: mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],eax

0x08048791 <+37>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8049b40

0x08048798 <+44>: call 0x8048650 <_ZNSirsERi@plt>

0x0804879d <+49>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [esp+0x1c]

0x080487a1 <+53>: cmp eax,0x4d2

0x080487a6 <+58>: je 0x80487af <main()+67>

0x080487a8 <+60>: mov eax,0x63

0x080487ad <+65>: jmp 0x80487c8 <main()+92>

; function call 3

0x080487af <+67>: mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],0x80488cb

0x080487b7 <+75>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8049be0

0x080487be <+82>: call 0x8048640 <_ZStlsISt11char_traitsIcEERSt13basic_ostreamIcT_ES5_PKc@plt>

0x080487c3 <+87>: mov eax,0x1

Function call 1

0x08048775 <+9>: mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],0x80488c0

0x0804877d <+17>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8049be0

0x08048784 <+24>: call 0x8048640 <_ZStlsISt11char_traitsIcEERSt13basic_ostreamIcT_ES5_PKc@plt>

We could start by looking at the arguments passed to the function to understand what its starting to do.

(gdb) > x/1s 0x80488c0

0x80488c0: "Passcode: "

Looks like we're calling COUT here. Moving on!

Function call 2

0x08048789 <+29>: lea eax,[esp+0x1c]

0x0804878d <+33>: mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],eax

0x08048791 <+37>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8049b40

0x08048798 <+44>: call 0x8048650 <_ZNSirsERi@plt>

0x0804879d <+49>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [esp+0x1c]

0x080487a1 <+53>: cmp eax,0x4d2

Here we're passing a pointer and an address to the function. After the function executes, we're comparing the pointer's value with 0x4d2 which is 1234 in decimal.

Looks like the function populates the pointer value. Which suggests its the CIN function.

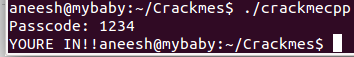

Are we done?

We just found gold! We found, that the program compares the value we give it against 1234 and makes a decision about based on it. Let's try entering 1234 in the passcode field.

We won!

Reversing is not about understand what the whole program does, its about getting an idea, doing experiments and understanding the relevant parts.

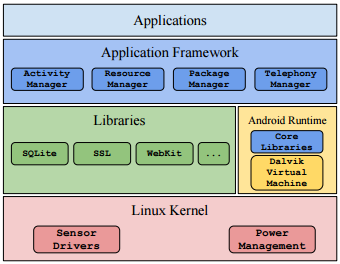

Android

Android runs a linux kernel underneath, with Android Runtimes and frameworks that makes running android applications possible.

Types/Parts of an android app

- Activity

- Service

- Content provider

- Broadcast reciever

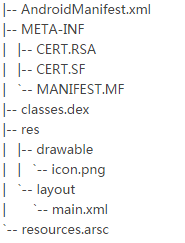

APK Structure

- AndroidManifest.xml contains details like name, version, referenced library files and more.

- Certificates are used to ensure the integrity of the android package, they usually contain public key of a trusted developer.

- Classes.dex is a java byte code file generated after the compilation using java source codes. Tools like Jd-gui and dex2jar can be used to decompile .dex files.

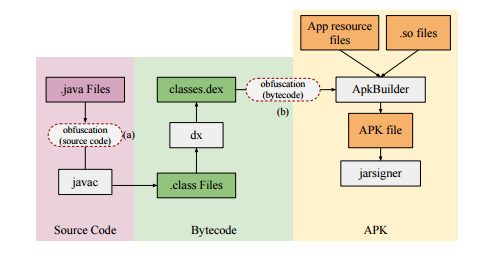

Building android applications

Android applications are written in java and executed in a Dalvik VM. The initial java files are first compiled into .class files, packed into a jar package and then compiled into .dex by the dx tool. The .dex file is then passed to the apkbuilder along with other assets and an APK file is created.

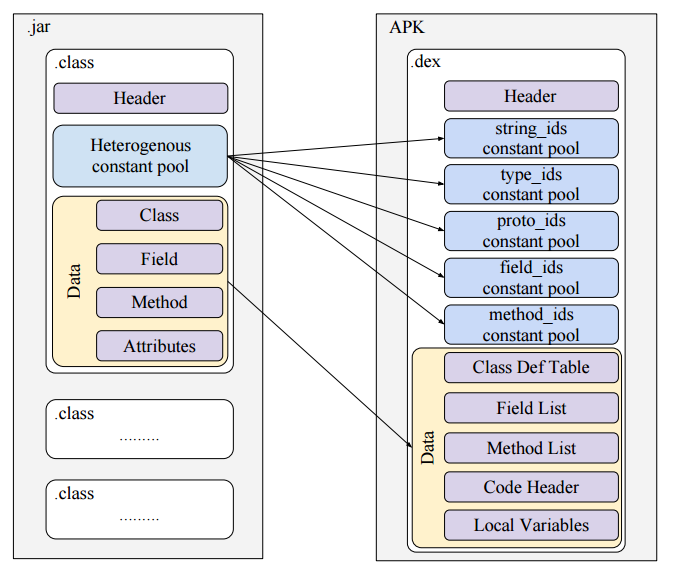

.dex

.dex optimizes the size of the file by deduplication of data. For example if there are 2 classes in our application using a similar string s, it would be repeated 2 times in .jar file while only once in .dex.

This causes .dex to be 44% smaller than .jar.

Android Packers!

Android packers are softwares that make android decompiling difficult.

The employ strategies to protect the code and to make it very difficult to get detected and debuggable.

Obfuscation

Obfuscation aims at preventing analysts from understanding the code.

Developers can also manually conduct obfuscation, such as, using native code. They can further obfuscate the correlation between Java code and native code by registering JNI methods with semantically meaningless names in the JNI OnLoad function. [1]

[1]: DexHunter: Toward Extracting Hidden Code from Packed Android Applications

Dynamic Loading

Android allows apps to load codes from external sources (in dex or jar format) at runtime. Packers usually encrypt the original jar file, decrypt and load it before running the app.

Anti-Debugging

Anti-debugging. Since Linux allows one process to attach to another process for debugging. Packed apps usually attach to themselves using ptrace.

As on linux only one process can attach to a process at a time. It prevents debuggers like GDB to debug packed application.

Current Techniques

Identities name scrambling

Its purpose is to obfuscate the program on an abstract level by replacing the meaningful names of variables, methods, classes, files with ones which provide no metadata information regarding the code.

APKfuscator - changes class names (in .dex) to >255 chars. Why 255?

Hiding in Resources

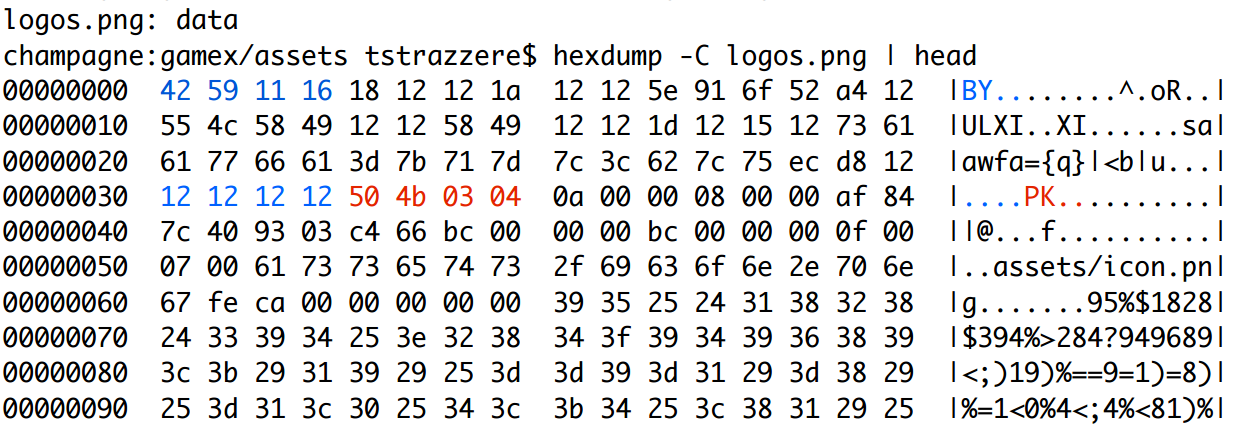

It is possible to hide bad-code in the resources of the application, in for example an image file like:

The first few bytes are rubbish. 50 4B 03 04 is the header magic number of a .zip archive.

File system hacks to change files

File systems like Mac's are case insensitive. We

The first few bytes are rubbish. 50 4B 03 04 is the header magic number of a .zip archive.

LIAP and Android Decompiling

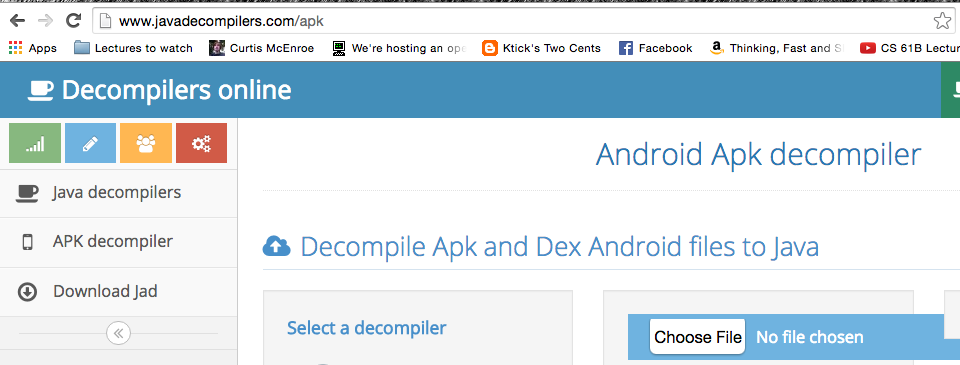

Decompiling android is really easy. You can use tools like Jadx decompiler to get readable code of the app. Lets try to decompile a hello world app using Jadx.

Decompile(Hello word)

I used an online utility that does the decompilation using jadx decompiler.

Decompile(Hello word)

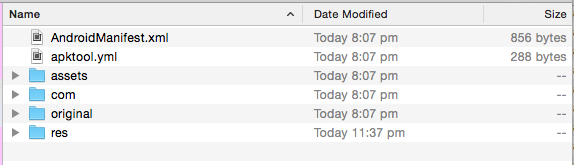

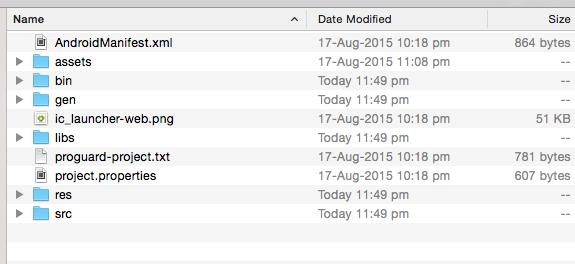

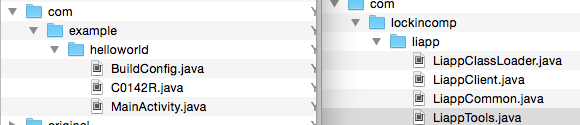

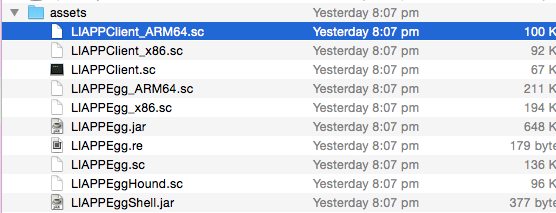

Directory structure

Here's what the directory structure of the app looked like:

Original

Decompiled

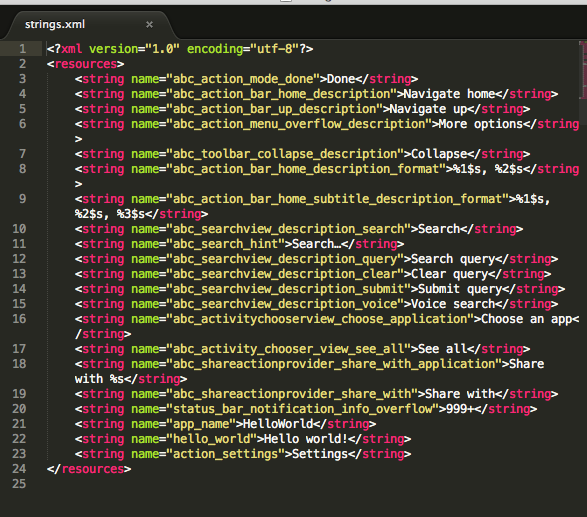

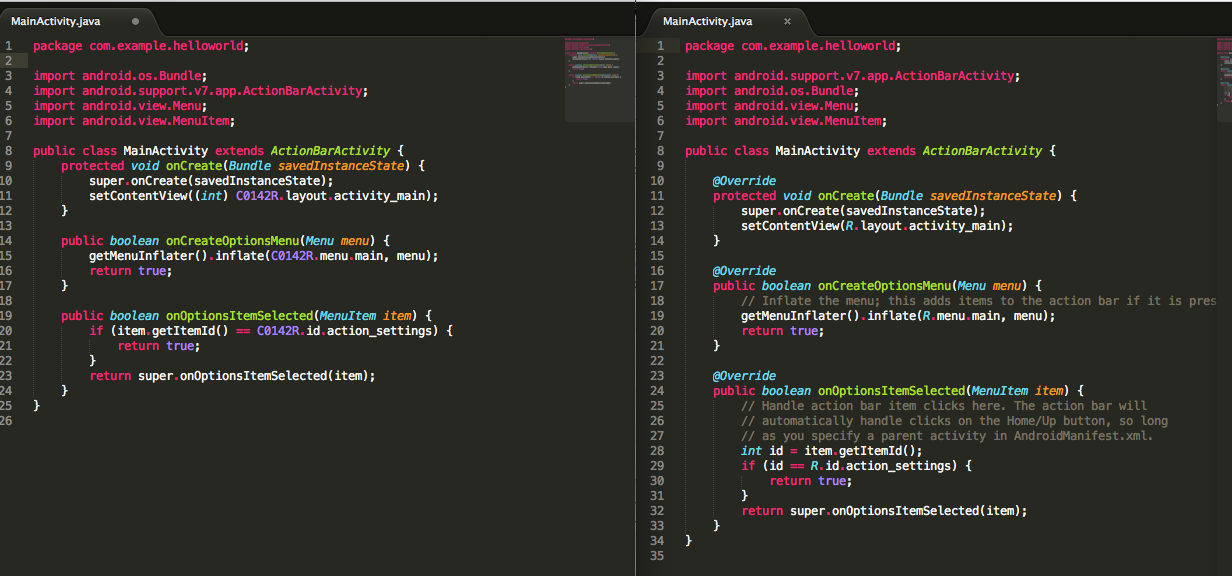

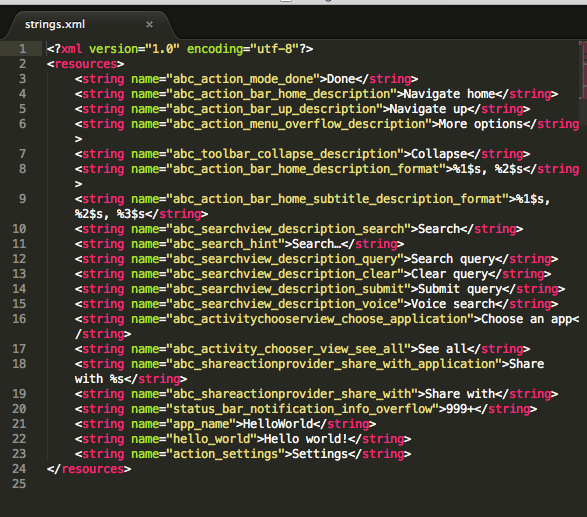

strings.xml

Here's what the directory structure of the app looked like:

Original

Decompiled

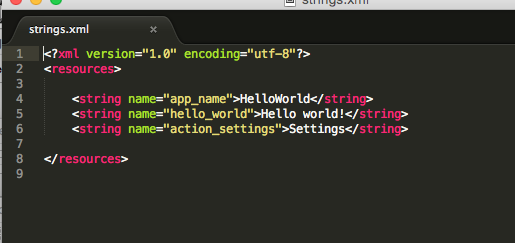

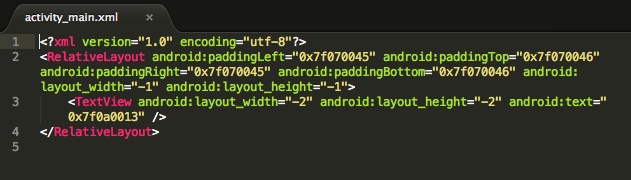

Activity main.xml

Activity main.xml here, defines the app's home screen's UI.

Original

Decompiled

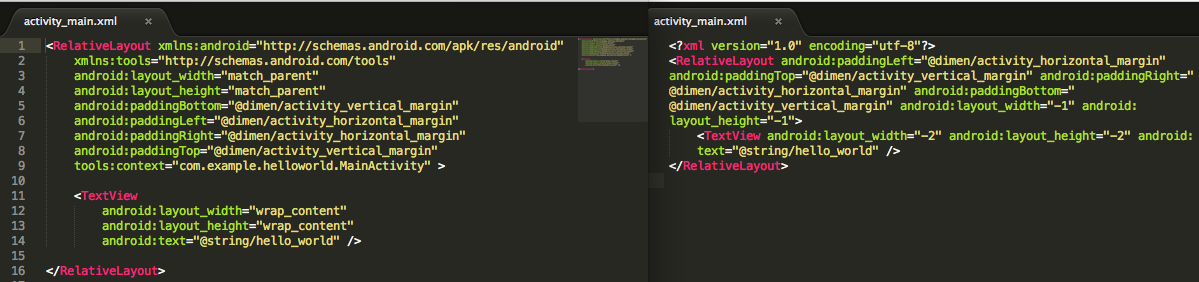

MainActivity.java

Decompiled

Original

Its the same exact code. That was an example to show why decompiling a Java APK is so easy!

Lets now try to use LIAPP.

LIAPP

LIAPP is a strong security protector that prevents the leakage of Android mobile app’s source

and neutralizes any types of threats including hacking, decompiling and debugging..

ActivityMain.xml

The android:text field is not a string anymore. Its changed to a hex, 0x7fa0013 instead of @string/hello_world.

MainActivity.java

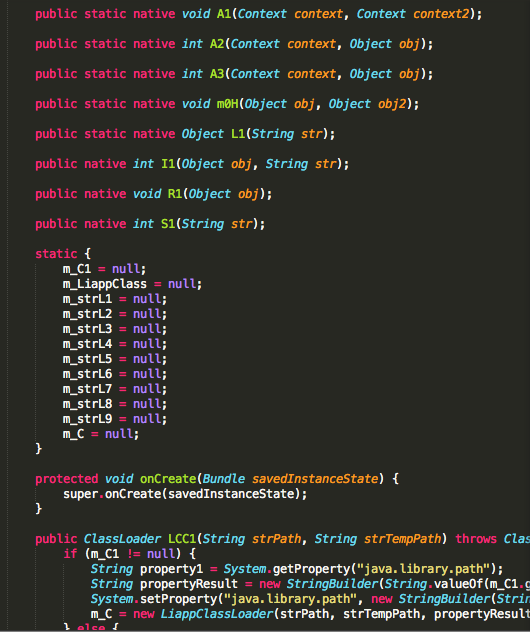

It looks like the MainActivity.java is packed in a set of files now.

Text

There is no MainActivity.java now. Lets look at the LIAPP files.

Strings.xml

The strings are unaffected through!

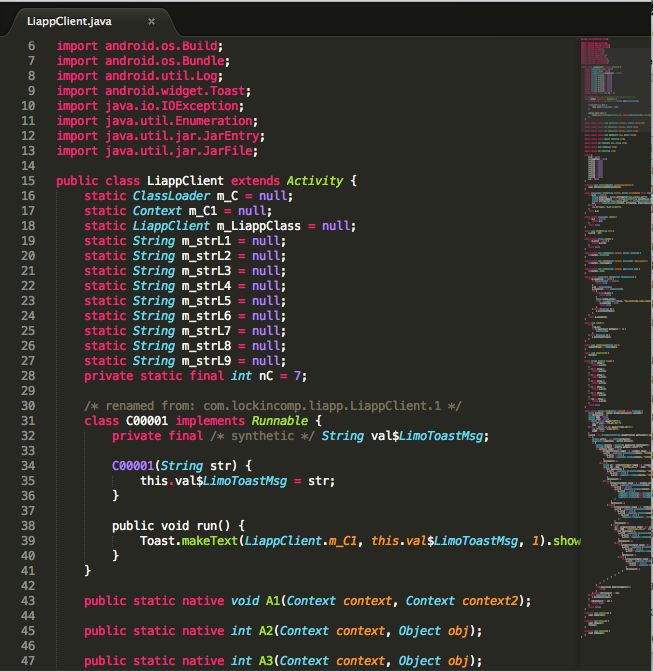

The Activity!

It now has a lot of functions with obfuscated names.

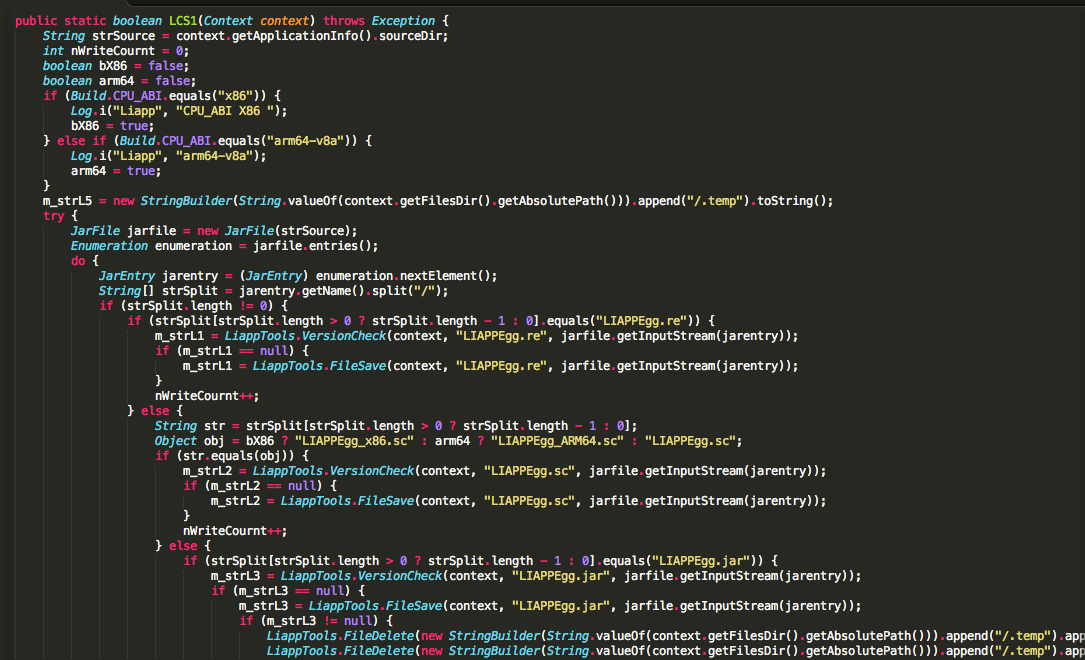

But wait there is more than just JAVA code now! :O LIAPP has a custom application context that it writes to an ELF file in assets.

It supports both x86 as well as ARM archs.

Assets

Original

LIAPP protected!

The app is driven by the android native code in assets.

I couldn't decompile the .jar or ELF files to understand what it does.

A paper discusses how to decompile dex files from heavily packed java applications like the ones you get after using LIAPP.

DexHunter doesn't depend on the approach you use to pack the application. It modifies the android runtime to extract the dex file.

When the first class is loaded the contents of the class is loaded in memory using dex hunter gets these contents and tries to rebuild the dex files to decompile the application.

DexHunter

Thanks

Reverse Enginnering 101

By Aneesh Dogra

Reverse Enginnering 101

- 1,073