Total Functions for Automated Reasoning

Building Terminating Theorem Provers

Alexander Gryzlov

(IMDEA Software Institute)

Lambda World 2025

October 24, Cádiz, Spain

Agenda

- AI & automated reasoning

- Total programming

- Unification

- SAT & DPLL

- Iterative DPLL

As you can guess/deduce from the title, this is a talk about combining two topics I've been working on for the past couple of years.

Agenda

- AI & automated reasoning

- Total programming

- Unification

- SAT & DPLL

- Iterative DPLL

Part 1

The domain:

AI & Automated Reasoning

AI is somewhat like "teenage music".

For every decade, it could mean something different:

- 1960s - The Beatles & Expert systems

- 1990s - Backstreet Boys & Spam filter/recommenders

- 2020s - Ariana Grande & Large Language Models

Let us go back to the basics!

AI through time

Classic AI tasks

- Machine translation and text comprehension

- Speech and pattern recognition

- Game playing (chess, checkers, Go, etc)

- Theorem proving

Formulated back in 1950s as "human-level activities performed by computer:"

We'll focus on the last one:

Here, symbolic (rather than statistical) methods are typically used, and precise guarantees matter the most.

Theorem proving landscape

- SAT/SMT solvers (Z3/cvc5)

- Computer algebra systems (Mathematica, MAPLE)

- Automated provers (Vampire, E, iProver)

- Logic programming languages (Prolog, λProlog, Datalog)

- Proof assistants (HOL, Coq, Agda, Lean)

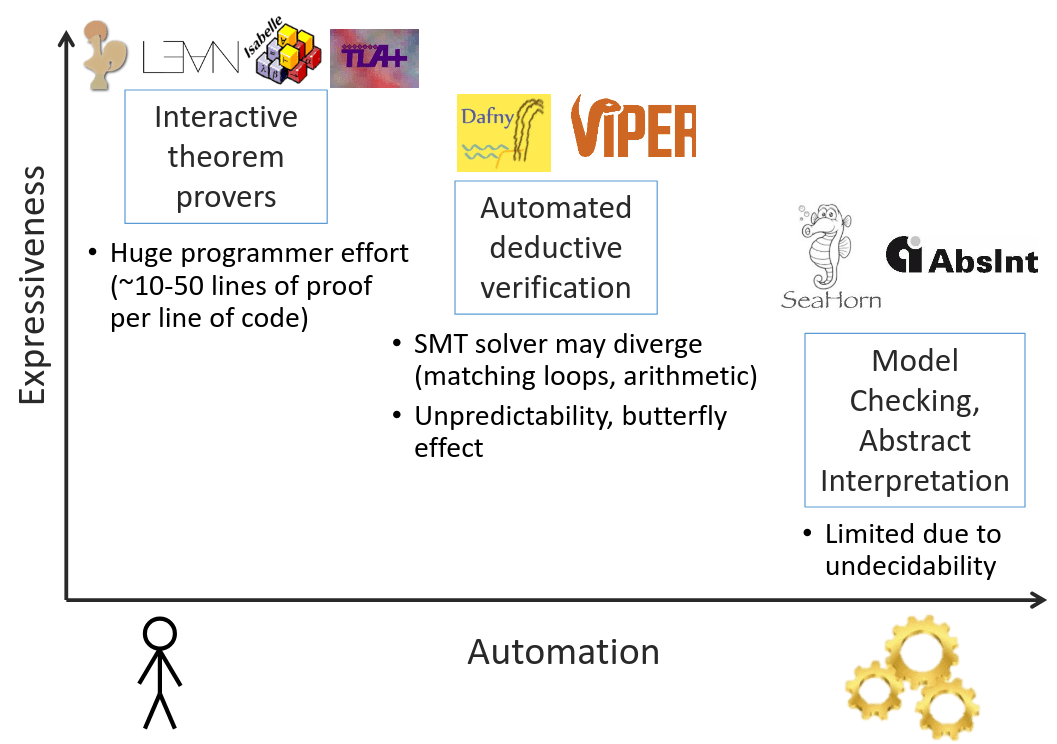

There's a struggle between the power of the system and automation.

More versatile systems converge toward general-purpose programming languages.

Automation vs power

We'll use an interactive tool (Agda) to build and verify some simple automated ones.

Shoham, [2019] "Verification of Distributed Protocols Using Decidable Logic"

Automated reasoning

The subfield of symbolic AI focused on theorem proving is referred to as "automated reasoning."

Typically involves:

- operating on syntax with variables

- synthesizing terms/proofs/refutations (not always)

- computing finite representations of functions (maps)

The algorithms we'll see use first-order syntax:

no binders (like λ) inside terms.

Variables and contexts

An important notion when reasoning about variables: context.

This is what logicians/type theorists write as capital Greek letters (Γ/Δ).

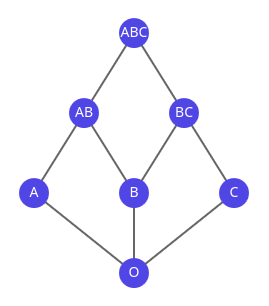

A finite set of all variables in the expression.

An overapproximation - can include extra variables not in the term!

We'll use a special (quotient) type Ctx for sets of variables (the order and multiplicity in it don't matter).

Has the usual set operators and predicates: ∈, union, rem, minus

Part 2

The technique:

Total programming

The nature of functions

We're going to compute maps/functions, but can we be precise about them?

(Pure) functions in FP are close to the mathematical definition of a function.

But how do we guarantee the "each" and "exactly one" part?

a function from a set X to a set Y assigns to each element of X exactly one element of Y

Computational functions

Two problems beyond purity:

- not every X is assigned a Y

- a Y is never produced

head :: [a] -> a

head [] = error "oops"

head (x:_) = xloop :: a -> a

loop x = loop xTermination matters

Can be costly in critical systems, we typically expect each request/component to finish, even if the system is interactive:

916 such CVE’s between 2000 and 2022

"Large-scale analysis of non-termination bugs in real-world OSS projects" (2022)

For reasoning algorithms, this means we always get an answer (though it may take a long time).

Total programming

We can only write programs which:

- cover all inputs

- terminate

The first part is relatively trivial (though often requires restructuring your program),

however the second involves recursion :(

Structural recursion

Programs which "consume" syntactically smaller pieces of input:

data Tree : 𝒰 where

leaf : Tree

node : Tree → Tree → Tree

depth : Tree → ℕ

depth leaf = 0

depth (node l r) = 1 + max (depth l) (depth r)

Beyond structural

Here's a simple example that doesn't fit this pattern:

Euclid's GCD algorithm

{-# TERMINATING #-}

gcd : ℕ → ℕ → ℕ

gcd n m =

if m == 0

then n

else gcd m (n % m) We know n % m < m but this is not structural!

gcd(105, 30) → 105%30 = 15

gcd(30, 15) → 30%15 = 0

gcd(15, 0) = 15

Well-founded recursion

We have to introduce a "measure" that decreases on a type T according to a well-founded order.

If you come up with any sequence ... < tx < ty < tz < ..., it cannot decrease forever.

A canonical type with such an order is (ℕ, <).

Any sequence will eventually end with 0.

Called a linear order, but orders can be branching.

Well-founded language

Let's introduce a special type for this goal:

record □_ (A : T → 𝒰) (x : T) : 𝒰 where

field call : (x : T) → y < x → A y

-----------------

fix : (A : T → 𝒰)

→ ({t : T} → □ A t → A t)

→ ({t : T} → A t)

-- a non-total fixpoint would be

-- fix : (A → A) → A□A means "A can only be called with an argument smaller than its index".

If the order is well-founded, we can implement the fixed-point combinator!

Well-founded language - sugar

-- implicit

fix : (A : T → 𝒰)

→ ({t : T} → □ A t → A t)

→ ({t : T} → A t)

-- sugar!

fix : (A : T → 𝒰)

→ ∀[ □ A ⇒ A ]

→ ∀[ A ] Sometimes we want to hide the decreasing argument (make it implicit), other

times it's crucial to computation.

-- explicit

fix : (A : T → 𝒰)

→ ((t : T) → □ A t → A t)

→ ((t : T) → A t)

-- sugar!

fix : (A : T → 𝒰)

→ Π[ □ A ⇒ A ]

→ Π[ A ] Well-founded GCD

Here's an example of computing a GCD function like this (uses the explicit form):

gcd-ty : ℕ → 𝒰

gcd-ty x = (y : ℕ) → y < x → ℕ

gcd-loop : Π[ □ gcd-ty ⇒ gcd-ty ]

gcd-loop x rec y y<x =

caseᵈ y = 0 of

λ where

(yes y=0) → x

(no y≠0) →

rec .call

-- it is safe to do the recursive call

y<x (x % y)

-- remainder is smaller

(%-r-< x y

(≱→< $ contra ≤0→=0 y≠0))gcd< : Π[ gcd-ty ]

gcd< = fix gcd-ty gcd-loop

gcd : ℕ → ℕ → ℕ

gcd x y =

caseᵗ x >=< y of

λ where

(LT x<y) → gcd< y x x<y

(EQ x=y) → x

(GT y<x) → gcd< x y y<xTo kick-start the computation, we just need to decide which argument goes first:

Part 3

The tutorial level:

Unification

Sometimes called "a Swiss army knife operator".

A family of (semi)algorithms for solving equations.

Match a pattern with gaps in it against data to fill the gaps.

Many applications:

- logic programming

- type inference

- 1st order logic provers

- program synthesis

- ...

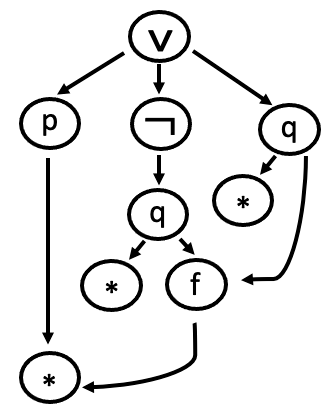

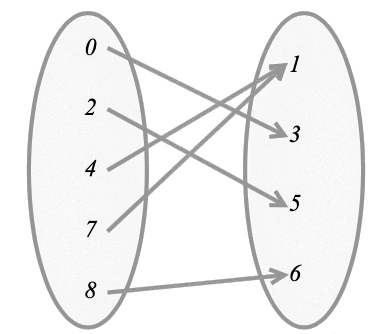

Unification

Most General Unifier

First-order MGU: a classical form described in Pierce's TAPL.

Given a pair of terms (or generally a list of pairs),

find a substitution that makes all of them equal (or fail):

A ≟ A {}

A ≟ B FAIL

A ≟ x { x ↦ A }

A ≟ B ⊗ C FAIL

x ≟ B ⊗ C { x ↦ B ⊗ C }

x ⊗ B ≟ A ⊗ y { x ↦ A , y ↦ B }

x ≟ x ⊗ x FAIL

[ x ≟ y

, y ≟ A ] { x ↦ A , y ↦ A }Terms & constraints

data Term : 𝒰 where

``_ : Var → Term

_⊗_ : Term → Term → Term

sy : String → Term

-- x ⊗ B

example : Term

example = `` x ⊗ sy "B"

Constr : 𝒰

Constr = Term × Term- Terms are just binary trees with two kinds of leaves

- Variables are an abstract type with equality (think ℕ/String)

- Constraints are pairs of terms

We need both internal and external substitution:

-- internal

sub1 : Var → Term → Term → Term

sub1 v t (`` x) =

if v == x then t else `` x

sub1 v t (p ⊗ q) =

sub1 v t p ⊗ sub1 v t q

sub1 v t (sy s) =

sy s

subs1 : Var → Term → List Constr → List Constr

-- external

Sub : 𝒰

Sub = Map Var TermUnification code

unify : List Constr → Maybe Subst

unify [] = just emptyM

unify ((tl, tr) ∷ cs) =

if tl == tr

then unify cs

else unifyHead tl tr cs

unifyHead : Term → Term

→ List Constr → Maybe Subst

unifyHead (`` v) tr cs =

if occurs v tr then nothing

else map (insertM v tr) $

unify (subs1 v tr cs)

unifyHead tl (`` v) cs =

... -- symmetrical

unifyHead (lx ⊗ ly) (rx ⊗ ry) cs =

unify ((lx , rx) ∷ (ly , ry) ∷ cs) -- adds constraints!

unifyHead _ _ _ =

nothingWhy does it terminate?

- Can't just count constraints - they increase for the ⊗ case

- Option 1: context size (count variables) - substitution removes variables; however, the context size stays the same for ⊗

- Option 2: count total term size in constraints - decreases for ⊗ (one level gets dismantled), but can grow for var case

tm-size : Term → ℕ

tm-size (p ⊗ q) = 1 + tm-size p + tm-size q

tm-size _ = 1

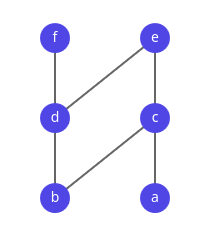

tm-sizes : List Constr → ℕSolution: combine 1 and 2!

Lexicographic order

We can combine two (or generally N) well-founded orders:

(a,b) < (x,y) := a < x OR (a = x AND b < y)

One component always decreases!

For unification this means:

- Either context decreases (var case),

- Or it stays the same but the total term size does (⊗ case)

Input : 𝒰

Input = Ctx × List Constr

wf-tm : Ctx → Term → 𝒰

wf-tm c t = vars t ⊆ c

wf-input : Input → 𝒰

-- each term in the constraint

-- list is WFunify-ty : ℕ × ℕ → 𝒰

unify-ty (x , y) =

(inp : Input)

→ wf-input inp

→ x = size (inp .fst)

→ y = term-sizes (inp .snd)

→ Maybe Sub

Terminating case for ⊗

-- before

unifyHead (lx ⊗ ly) (rx ⊗ ry) cs =

unify ((lx , rx) ∷ (ly , ry) ∷ cs)

-- after

unify-head-loop rec (ctx , cs) wf (lx ⊗ ly) (rx ⊗ ry) wl wr ex ey =

rec .call prf-<

(ctx , ls') prf-wf

refl refl

where

cs' : List Constr

cs' = (lx , rx) ∷ (ly , ry) ∷ cs

prf-< : (size ctx , term-sizes cs') < (size ctx , term-sizes cs)

prf-< = ...

prf-wf : wf-input (ctx , cs')

prf-wf = ...Part 4

The main quest:

SAT & DPLL

The SAT problem

Classical constraint satisfaction task:

Given a boolean formula with variables,

find an assignment of variables that makes it true (or fail).

Compared to unification:

- we restrict the range of variables (only True/False)

- but we add a semantical constraint (Boolean evaluation)

The SAT problem examples

-- tautologies (true for every assignment)

True

P ∧ Q ⇒ P ∨ Q

((P ⇒ Q) ⇒ P) ⇒ P -- aka Peirce's law

-- satisfiable (there is an assignment)

P ∧ Q ⇒ Q ∧ R -- P = Q = True, R = False

-- simplifes to True ⇒ False

-- unsatisfiable

P ∧ ¬P

Exponential search

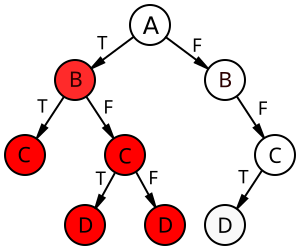

- The most widely used approach is backtracking search

- Naively we can try each variable and flip a previous choice when getting

False - However that's 2ⁿ operations where n = #variables

- Can we do better?

Generally, in the worst case, no! :(

Cook–Levin theorem (1971): SAT is NP-complete

(btw, this is the birth of NP-completeness concept).

But some heuristics can make less-than-worst cases tractable.

DPLL

Davis–Putnam–Logemann–Loveland algorithm, 1961

- Still fundamentally performs backtracking search

- But uses 3 heuristics to prune the search substantially

- These are unit propagation, pure literal rule and literal selection

CNF

DPLL and similar algorithms assume the input is in a

conjunctive normal form: a big conjunction of disjunctions of possibly negated literals (clauses)

( A ∨ ¬B)

∧ (¬C ∨ D ∨ E)

∧ ... We can always transform into one thanks to boolean reasoning principles (i.e. DeMorgan rule: ¬(P ∨ Q) = ¬P ∧ ¬Q)

True ~ ∅

False ~ ()

P ∨ Q ~ (P ∨ Q)

P ∧ Q ~ (P) ∧ (Q)

P ∧ Q ⇒ Q ∧ R ~ (¬P ∨ ¬Q ∨ R)CNF encoding

data Lit (Γ : Ctx) : 𝒰 where

Pos : (v : Var) → v ∈ Γ → Lit Γ

Neg : (v : Var) → v ∈ Γ → Lit Γ

var : Lit Γ → Var

var (Pos v _) = v

var (Neg v _) = v

positive : Lit Γ → Bool

positive (Pos _ _) = true

positive _ = falseUnlike in unification, we push the well-formedness constraint into the literals:

Clause : Ctx → 𝒰

Clause Γ = List (Lit Γ)

CNF : Ctx → 𝒰

CNF Γ = List (Clause Γ)

literals : CNF Γ → List (Lit Γ)

literals = nub ∘ concatUnit propagation aka 1-literal rule

unit-clause : CNF Γ → Maybe (Lit Γ)

unit-clause [] = nothing

unit-clause ( [] ∷ c) = unit-clause c

unit-clause ((x ∷ []) ∷ c) = just x

unit-clause ((_ ∷ _ ∷ _) ∷ c) = unit-clause c

unit-propagate : (l : Lit Γ) → CNF Γ → CNF (rem (var l) Γ)

unit-propagate l [] = []

unit-propagate l (f ∷ c) =

if has l f

then unit-propagate l c

else delete-var (var l) f ∷ unit-propagate l c

one-lit-rule : CNF Γ → Maybe (Σ[ l ꞉ Lit Γ ] (CNF (rem (var l) Γ)))

one-lit-rule cnf =

map (λ l → l , unit-propagate l cnf) $

unit-clause cnfHeuristic 1: If a clause consists of a single literal, it must be true, propagate it through the formula:

(A ∨ ¬B)

∧ (C)

∧ ... Pure literal rule

pure-literal-rule :

(c : CNF Γ)

→ (Σ[ purelits ꞉ List (Lit Γ) ]

(let vs = map var purelits in

(vs ≬ Γ) × CNF (minus Γ vs)))

⊎ (∀ {l} → l ∈ literals c → negate l ∈ literals c)

...Heuristic 2 (aka affirmative-negative rule):

The idea is to delete every literal that occurs strictly positively or strictly negatively (purely).

Literal selection

posneg-count : CNF Γ → Lit Γ → ℕ

posneg-count cnf l =

let m = count (has l) cnf

n = count (has $ negate l) cnf

in

m + n

splitting-rule : (c : CNF Γ)

→ Any positive (literals c)

→ Lit Γ

The previous two rules try to eliminate guessing as much as possible, but eventually, we're going to have to guess a value.

This is where backtracking still happens.

The splitting rule guarantees a result after the pure literal one.

Putting it all together

Answer = Map Var Bool

dpll-loop : (CNF Γ → Maybe Answer)

→ CNF Γ → Maybe Answer

dpll-loop rec cnf =

if null? cnf then just emptyM -- trivially true

else if has [] cnf then nothing -- trivially false

else

maybe

(maybe

(let l = splitting-rule cls in

map (either (insertLit l)

(insertLit (negate l))) $

rec (unit-propagate l cnf)

<+> rec (unit-propagate (negate l) cnf))

(λ (ls , c) → map (insertLits ls) $ rec c)

(pure-literal-rule cnf))

(λ (l , c) → map (insertLit l) $ rec c)

(one-lit-rule cnf)

Why does this terminate?

Context always decreases:

- For unit propagation by 1

- For pure literal by some n ≥ 1

- For recursive call by 1

This is actually simpler than unification!

We don't need the lexicographic pair, just a single number:

DPLL-ty : ℕ → 𝒰

DPLL-ty x =

{Γ : Ctx}

→ x = size Γ

→ CNF Γ → Maybe Answer

Part 5

The boss fight:

Iterative DPLL

Iterative DPLL

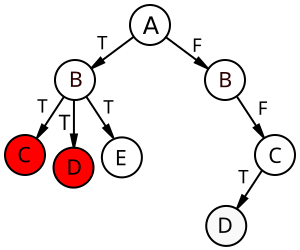

- Again, the core of the algorithm is backtracking search

- However, the backtracking information is kept on the system stack - no tail recursion

- Actual implementations work tail-recursively (iteratively)

...

(map (either (insertLit l)

(insertLit (negate l))) $

rec (unit-propagate l cls)

<+> rec (unit-propagate (negate l) cls))

...Trail blazing

- We make the stack a first-class object, usually called a trail

- Need add a flag do determine if the literal is guessed, which then serves as a backtrack point

data Flag : 𝒰 where

guessed deduced : Flag

Trail : Ctx → 𝒰

Trail Γ = List (Lit Γ × Flag)

trail-lits : Trail Γ → List (Lit Γ)

trail-lits = map fst

trail→answer : Trail Γ → Answer

trail→answer =

fold-r emp λ (l , _) → upd (var l) (positive l)Heuristics redux

unit-subpropagate-loop : (CNF Γ → Trail Γ → CNF Γ × Trail Γ)

→ CNF Γ → Trail Γ → CNF Γ × Trail Γ

unit-subpropagate-loop rec cnf tr =

let cnf' = map (filter (not ∘ trail-has tr ∘ negate)) cnf

newunits = literals (filter (is-fresh-unit-clause tr) cnf')

in

if null newunits

then (cnf' , tr)

else loop cnf' (map (λ l → l , deduced) newunits ++ tr)

We get rid of the pure literal rule but perform unit propagation in batches:

Iterative DPLL loop

backtrack : Trail Γ → Maybe (Lit Γ × Trail Γ)

backtrack [] = nothing

backtrack ((_ , deduced) ∷ ts) = backtrack ts

backtrack ((p , guessed) ∷ ts) = just (p , ts)

dpli-loop : CNF Γ

→ (Trail Γ → Maybe Answer)

→ Trail Γ → Maybe Answer

dpli-loop cnf rec tr =

let (cnf' , tr') = unit-subpropagate cnf tr in

if has [] cnf' then -- reached False

maybe

nothing

(λ (p , trb) → rec ((negate p , deduced) ∷ trb))

(backtrack tr)

else

...Then we either run into an inconsistency and have to backtrack:

Iterative DPLL loop

dpli-loop : CNF Γ

→ (Trail Γ → Maybe Answer)

→ Trail Γ → Maybe Answer

dpli-loop cnf rec tr =

let (cnf' , tr') = unit-subpropagate cnf tr in

if has [] cnf' then

...

else -- need to guess

let ps = unassigned cls tr' in

if null ps

then just (trail→answer tr')

else rec ((splitting-rule' cls ps , guessed) ∷ tr)Or we have to make a choice:

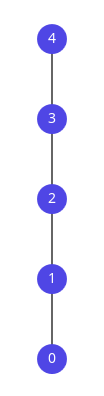

Why does any of this terminate?

For unit propagation, the measure is the count of literals still unused in the trail:

(x2 because of polarity)

y = 2 · size Γ ∸ length trHowever this, only works when the trail is unique (invariant #1)

Main loop termination

For the guess case, the unused trail literals also work:

We take the old trail and add a new literal onto it, exhausting unused ones.

But what about the backtracking case?

Here trb is a suffix of the old trail - it shrinks!

We had the same situation in unification: two kinds of recursive calls, one decreases a measure, the other one increases.

Looks like we need to use the lexicographic product again, but with what?

rec ((splitting-rule' cls ps , guessed) ∷ tr)rec ((negate p , deduced) ∷ trb)Main loop termination - idea

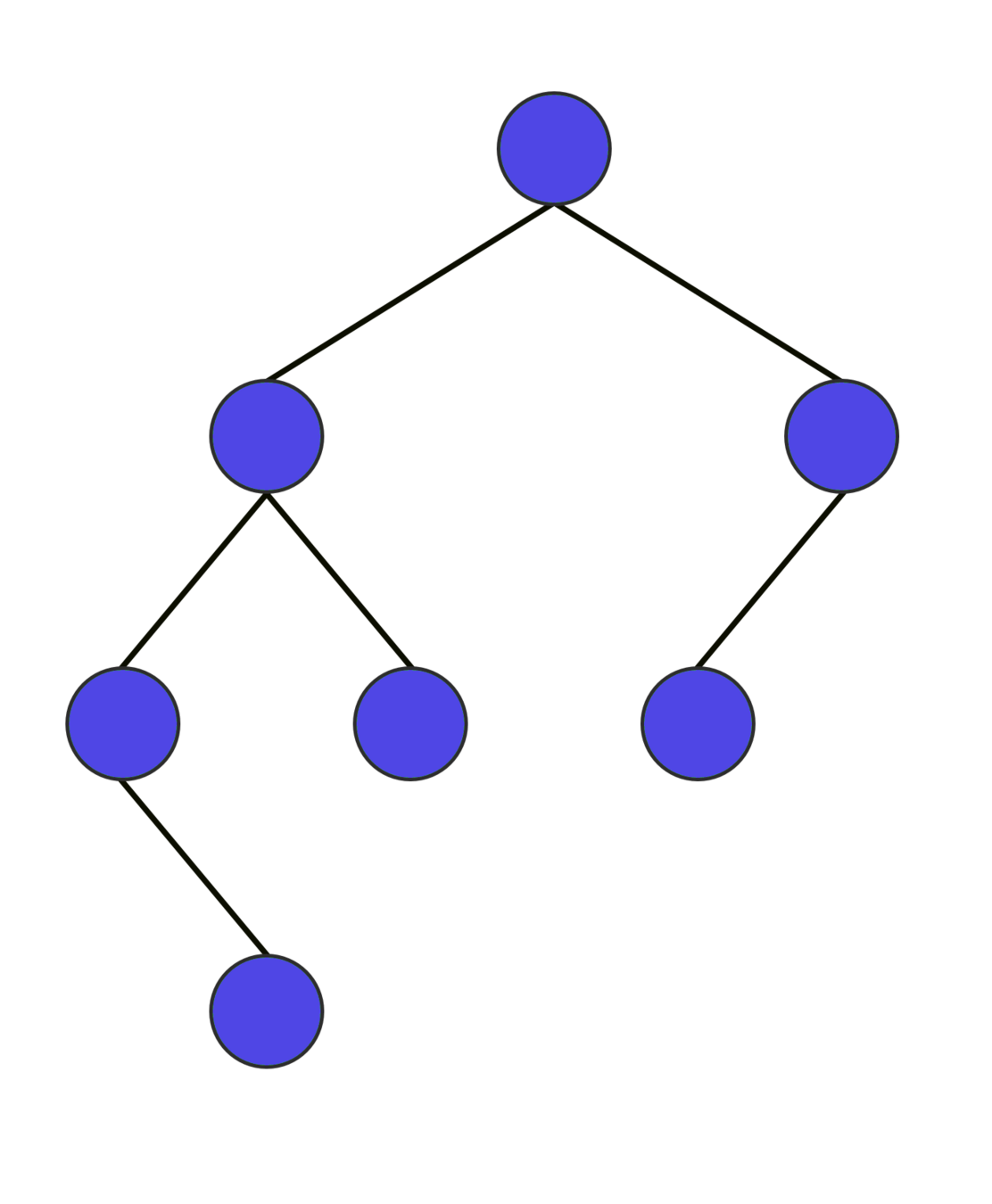

- Intuitively, it's the search space that decreases for backtracking

- But the search tree is generated on the fly

- We need to find a proxy

If we look closely at this tree, we notice that

we never return to discarded branches.

So what sticks around is rejected literals.

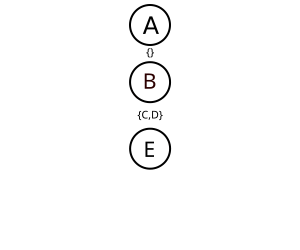

Main loop termination - measure

- However, we can't lump them all together - the deduced literals get discarded after backtracking.

- We need to keep a vector of these rejected sets.

- The first part of the measure, then, is a vector of counts of still-available literals.

The full measure is then a lexicographic product of a vector (N-ary product) of non-rejected assignments corresponding to the guessed level and the number of unused variables in the trace!

(whew)

DPLI termination invariants

For all of this to work, we need the old trail uniqueness invariant and a new one:

- Variable + polarity should not repeat

- If a guessed variable is in the trail, its negation doesn't appear before it

The rejected vector/stack also needs an invariant:

If a variable is on level n, its negation appears in the trail after dropping the first n guessed variables.

Just need to prove that all of these are preserved :/

Uniq (trail-lits tr) ×

(∀ x → (x , guessed) ∈ tr

→ negate x ∉ tail-of x (trail-lits tr))

∀ x (f : Fin (size Γ))

→ x ∈ lookup rj f

→ negate x ∈ (trail-lits $ drop-guessed tr (count-guessed tr ∸ fin→ℕ f))

DPLI termination type

DPLI-ty : {Γ : Ctx} → Vec ℕ (size Γ) × ℕ → 𝒰

DPLI-ty {Γ} (x , y) =

(tr : Trail Γ)

→ Trail-invariant tr

→ (rj : Rejectstack Γ)

→ Rejectstack-invariant rj tr

→ x = map (λ q → 2 · size Γ ∸ size q) rj

→ y = 2 · size Γ ∸ length tr

→ Maybe Answer

Conclusion

Lessons learned

- Writing out termination proofs forces you to understand how the algorithm actually works, in the form of its invariants.

- Control flow tricks make termination harder :(

- Once you determine the invariants, you have more freedom to restructure your algorithm, make it more modular, experiment with different representations, and so on.

Lessons learned

- More generally, from a mathematical point of view, automated reasoning is about syntax, finite sets, maps, and intricate order relations.

- And order theory is just a cut-down version of category theory, but that is a story for another time...

References

- Automated Reasoning @ SEP

- Shi, Xie, Li, Zhang, Chen, Li, [2022] "Large-scale analysis of non-termination bugs in real-world OSS projects"

-

Cook, Podelski, Rybalchenko, [2011] "Proving program termination"

-

Hoder, Voronkov, [2009] "Comparing unification algorithms in first-order theorem proving"

-

Vardi, [2015] "The SAT Revolution: Solving, Sampling, and Counting"

-

Harrison, [2009] "Handbook of Practical Logic and Automated Reasoning"

Contacts & repo

Acknowledgments

Partially funded by the European Union (GA 101039196). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the European Research Council can be held responsible for them.

Total Functions for Automated Reasoning: Building Terminating Theorem Provers

By Alex Gryzlov

Total Functions for Automated Reasoning: Building Terminating Theorem Provers

LambdaWorld'25 talk

- 44